On the one hand, it is easy to understand why the popularity of agile for data warehousing lags 10 years behind its usage for general applications. It is hard to envision delivering any DWBI capabilities quickly. For data capture applications, creating a new element requires simply creating a column for it in the database and then dropping an entry field for it on the screen. To deliver a new warehousing attribute, however, a team has to create several distinct programs to extract, scrub, integrate, and dimensionalize the data sets containing the element before it can be placed on the end user’s console. Compared to the single transaction application challenge that agile methods originally focused on, data warehousing projects are trying to deliver a half-dozen new applications at once. They have too many architectural layers to manage for a team to update the data transform logic quickly in order to satisfy a program sponsor’s latest functional whim.

On the other hand, data warehousing professionals need to be discussing agile methods intently, because every year more business intelligence departments large and small are experimenting with rapid delivery techniques for analytic and reporting applications. To succeed, they are adapting the generic agile approaches somewhat, but not beyond recognition. These adaptations make the resulting methods one notch more complex than agile for transaction-capture systems, but they are no less effective. In practice, agile methods applied properly to large data integration and information visualization projects have lowered the development hours needed and driven coding defects to zero. All this is accomplished while placing a steady stream of new features before the development team’s business partner. By saving the customer time and money while steadily delivering increments of business value, agile methods for BI projects go a long way toward solving the challenges many DWBI departments have with pleasing their business customers.

For those readers who are new to agile concepts, this chapter begins with a sketch of the method to be followed throughout most of this book. The next sections provide a high-level contrast between traditional development methods and the agile approach, and a listing of the key innovative techniques that give agile methods much of their delivery speed. After surveying evidence that agile methods accelerate general application development, the presentation introduces a key set of adaptations that will make agile a productive approach for data warehousing. Next, the chapter outlines two fundamental challenges unique to data warehousing that any development method must address in order to succeed. It then closes with a guide to the remainder of the book and a second volume that will follow it.

A quick peek at an agile method

The practice of agile data warehousing is the application of several styles of iterative and incremental development to the specific challenges of integrating and presenting data for analytics and decision support. By adopting techniques such as colocating programmers together in a single workspace and embedding a business representative in the team to guide them, companies can build DWBI applications without a large portion of the time-consuming procedures and artifacts typically required by formal software development methods. Working intently on deliverables without investing time in a full suite of formal specifications necessarily requires that developers focus only on a few deliverables at time. Building only small pieces at a time, in turn, repeats the delivery process many times. These repeated deliveries of small scopes place agile methods in the category of “iterative and incremental development” methods for project management.

When following agile methods, DWBI developers essentially roll up their sleeves and work like they have only a few weeks before the system is due. They concentrate on the most important features first and perform only those activities that directly generate fully shippable code, thus realizing a tremendous boost in delivery speed. Achieving breakthrough programming speeds on a BI project will require developers to work differently than most of them are trained, including the way they define requirements, estimate work, design and code their systems, and communicate results to stakeholders, plus the way they test and document the resulting system modules. To make iterative and incremental delivery work, they will also need to change the physical environment in which they work and the role of the project manager. Most traditional DWBI departments will find these changes disorienting for a while, but their disruption will be more than compensated for by the increased programmer productivity they unleash.

Depending on how one counts, there are at least a dozen agile development styles to choose from (see sidebar). They differ by the level of ongoing ceremonies they follow during development and the amount of project planning they invest in before coding begins. By far the most popular flavor of agile is Scrum, first introduced in 1995 by Dr. Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber. [Schwaber 2004] Scrum involves a small amount of both ceremony and planning, making it fast for teams to learn and easy for them to follow dependably. It has many other advantages, among them being that it

• Adroitly organizes a team of 6 to 10 developers

• Intuitively synchronizes coding efforts with repeated time boxes

• Embeds a business partner in the team to maximize customer engagement

• Appeals to business partners with its lightweight requirements artifacts

• Double estimates the work for accuracy using two units of measure

• Forecasts overall project duration and cost when necessary

• Includes regular self-optimizing efforts in every time box

• Readily absorbs techniques from other methods

Agile Development Methods

| Adaptive | [Highsmith 1999] |

| Crystal | [Cockburn 2004] |

| Disciplined Agile Delivery | [Ambler 2012] |

| Dynamic Systems Development Method (DSDM) | [Stapleton 2003] |

| Extreme Programming (XP) | [Beck 2004] |

| Feature Driven Development (FDD) | [Palmer 2002] |

| Lean Development | [Poppendieck 2003] |

| Kanban | [Anderson 2010] |

| Pragmatic | [Hunt 1999] |

| Scrum | [Cohn 2009] |

| Unified Processes (Essential, Open, Rational, etc.) | [Jacobson, Booch, & Rumbaugh 1999] |

Scrum has such mindshare that, unless one clarifies he is speaking of another approach, Scrum is generally assumed to be the base method whenever one says “agile.” Even if that assumption is right, however, the listener still has to interpret the situation with care. Scrum teams are constantly optimizing their practices and borrowing techniques from other sources so that they all quickly arrive at their own particular development method. Over time Scrum teams can vary their practice considerably, to the point of even dropping a key component or two such as the time box. Given this diversity in implementations, this book refers to Scrum when speaking of the precise method as defined by Sutherland and Schwaber. It employs the more general term “agile” when the context involves an ongoing project that may well have started with Scrum but then customized the method to better meet the situation at hand.

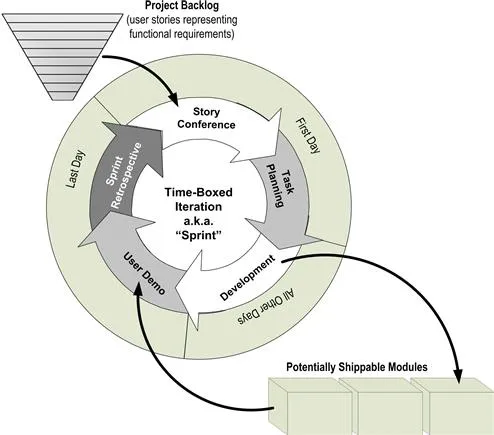

Figure 1.1 depicts the simple, five-step structure of an iteration with which Scrum teams build their applications. A team of 6 to 10 individuals—including an embedded partner from the customer organization that will own the applications—repeats this cycle every 2 to 8 weeks. The next chapter presents the iteration cycle in detail. Here, the objective is to provide the reader with enough understanding of an agile approach to contrast it with a traditional method.

Figure 1.1 Structure of Scrum development iteration and duration of its phases.

As shown in Figure 1.1, a list of requirements drives the Scrum process. Typically this list is described as a “backlog of user stories.” User stories are single sentences authored by the business stating one of their functional needs. The embedded business partner owns this list, keeping it sorted by each story’s importance to the business. With this backlog available, Scrum teams repeatedly pull from the top as many stories as they can manage in one time box, turning them into shippable software modules that satisfy the stated needs. In practice, a minority of the stories on a backlog include nonfunctional features, often stipulated for the application by the project architect. These “architectural stories” call for reusable submodules and features supporting quality attributes such as performance and scalability. Scrum does not provide a lot of guidance on where the original backlog of stories comes from. For that reason, project planners need to situate the Scrum development process in a larger project life cycle that will provide important engineering and project management notions such as scope and funding, as well as data and process architecture.

The standard development iteration begins with a story conference where the developers use a top-down estimating technique using what are called “story points” to identify the handful of user stories at the top of the project’s backlog that they can convert into shippable code during the iteration.

Next, the team performs task planning where it decomposes the targeted user stories into development tasks, this time estimating the work bottom-up in terms of labor hours in order to confirm that they have not taken on too much work for one iteration.

After confirming they have targeted just the right amount of work, the teammates now dive into the development phase, where they are asked to self-organize and create over the next couple of weeks the promised enhancement to the application, working in the most productive way they can devise. The primary ceremony that Scrum places upon them during this phase is that they check in with each other in the morning via a short stand-up meeting, that is, it asks them to hold a daily “scrum.”

At the end of the cycle, the team conducts a user demo where the business partner on the team operates the portions of the application that the developers have just completed, often with other business stakeholders looking on. For data integration projects that have not delivered the information yet to a presentation layer, the team will typically provide a simple front end (perhaps a quickly built, provisional BI module) so that the business partner can independently explore the newly loaded data tables. The business partner evaluates the enhanced application by considering each user story targeted during the story conference, deciding whether the team has delivered the functionality requested.

Finally, before beginning the cycle anew, the developers meet for a sprint retrospective, where they discuss the good and bad aspects of the development cycle they just completed and brainstorm new ways to work together during the next cycle in order to smooth out any rough spots they may have encountered.

At this point, the team is ready to start another cycle. These iterations progress as long as there are user stories on the project’s backlog and the sponsors continue funding the project. During an iteration’s development phase, the team’s embedded business partner may well have reshuffled the order of the stories in the backlog, added some new one, and even discarded others. Such “requirements churn” does not bother the developers because they are always working within the near-planning horizon defined by the iteration’s time box. Because Scrum has the developers constantly focused on only the top of the backlog, the business can steer the team in a completely new direction every few weeks, heading to wherever the project needs to go next. Such flexibility often makes business partners very fond of Scrum because it allows the developers from the information technology (IT) department to become very flexible and responsive.