We illustrate the need for data integration with two examples, one representing a typical scenario that may occur within a company and the other representing an important kind of search on the Web.

Example 1.1

Consider FullServe, a company that provides Internet access to homes, but also sells a few products that support the home computing infrastructure, such as modems, wireless routers, voice-over-IP phones, and espresso machines. FullServe is a predominantly American company and recently decided to extend its reach to Europe. To do so, FullServe acquired a European company, EuroCard, which is mainly a credit card provider, but has recently started leveraging its customer base to enter the Internet market.1

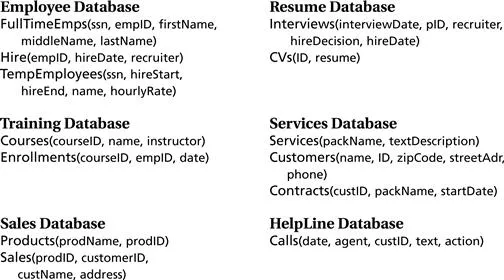

The number of different databases scattered across a company like FullServe could easily reach 100. A very simplified version of FullServe’s database collection is shown in Figure 1.1. The Human Resources Department has a database storing information about each employee, separating full-time and temporary employees. They also have a separate database of resumes of each of their employment candidates, including their current employees. The Training and Development Department has a database of the training courses (internal and external) that each employee went through. The Sales Department has a database of services and its current subscribers and a database of products and their customers. Finally, the Customer Care Department maintains a database of calls to their help-line center and some details on each such call.

Figure 1.1 Some of the databases a company like FullServe may have. For each database, we show some of the tables and for each table, some of its attributes. For example, the Employee database has a table FullTimeEmps with attributes ssn, empID, firstName, middleName, and lastName.

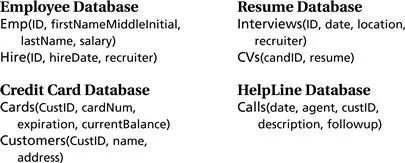

Upon acquiring EuroCard, FullServe also inherited their databases, shown in Figure 1.2. EuroCard has some databases similar to those of FullServe, but given their different location and business focus, there are some obvious differences.

Figure 1.2 Some of the databases of EuroCard. Note that EuroCard organizes its data quite differently from FullServe. For example, EuroCard does not distinguish between full-time and part-time employees. FullServe records the hire data of employees in the Resume database and the Employee database, while EuroCard only records the hire date in the Employee database.

There are many reasons why data reside in multiple databases throughout a company, rather than sitting in one neatly organized database. As in the case of FullServe and EuroCard, databases are acquired through mergers and acquisitions. When companies go through internal restructuring they don’t always align their databases. For example, while the services and products divisions of FullServe are currently united, they probably didn’t start out that way, and therefore the company has two separate databases. Second, most databases originate from a particular group in a company that has an information need at a particular point in time. When the database is created, its authors cannot anticipate all information needs of the company in the future, and how the data they are producing today may be used differently at some other point in time. For example, the Training database at FullServe may have started as a small project by a few employees in the company to keep track of who attended certain training sessions in the company’s early days. But as the company grew, and the Training and Development Department was created, this database needed to be broadened quite a bit. As a result of these factors and others, large enterprises typically have dozens, if not hundreds, of disparate databases.

Let us consider a few example queries that employees or managers in FullServe may want to pose, all of which need to span multiple databases.

• Now that FullServe is one large company, the Human Resources Department needs to be able to query for all of its employees, whether in the United States or in Europe. Because of the acquisition, data about employees are stored in multiple databases: two databases (for employees and for temps) on the American side of the company and one on the European side.

• FullServe has a single customer support hotline, which customers can call about any service or product they obtain from the company. It is crucial that when a customer representative is on the phone with a customer, he or she sees the entire set of services the customer is getting from FullServe, whether it be Internet service, credit card, or products purchased. In particular, it is useful for the representative to know that the customer on the phone is a big spender on his or her credit card, even if he or she is calling about a problem with his or her Internet connection. Obtaining such a complete view of the customer requires obtaining data from at least three databases, even in our simple scenario.

• FullServe wants to build a Web site to complement its telephone customer service line. On the Web site, current and potential customers should be able to see all the products and services FullServe provides, and also select bundles of services. Hence, a customer must be able to see his or her current services and obtain data about the availability and pricing of any other services. Here, too, we need to tap into multiple databases of the company.

• To take the previous example further, suppose FullServe partners with a set of other vendors to provide branded services. That is, you can get a credit card issued by your favorite sports team, but the credit card is actually served by FullServe. In this case, FullServe needs to provide a Web service that will be accessed by other Web sites (e.g., those of the sports teams) to provide a single login point for customers. That Web service needs to tap into the appropriate databases at FullServe.

• Governments often change reporting or ethic laws concerning how companies can conduct business. To protect themselves from possible violations, FullServe may want to be proactive. As a first step, the company may want to be aware of employees who’ve worked at competing or partner companies prior to joining FullServe. Answering such a query would involve combining data from the Employee database with the Resume database. The additional difficulty here is that resumes tend to be unstructured text, and not nicely organized data.

• Combining data from multiple sources can offer opportunities for a company to obtain a competitive advantage and find opportunities for improvement. For an example of the former, combining data from the HelpLine database and the Sales database will help FullServe identify issues in their products and services early on. Discovering trends in the usage of different products can enable FullServe to be proactive about building and maintaining inventory levels. Going further, suppose we find that in a particular area of the country FullServe is receiving an unusual number of calls about malfunctions in their service. A more careful look at this data may reveal that the services were installed by agents who had taken a particular training course, which was later found to be lacking. Finding such a pattern in the data requires combining data from the Training database, HelpLine database, and Services database, all residing in very different parts of the company.

Example 1.2

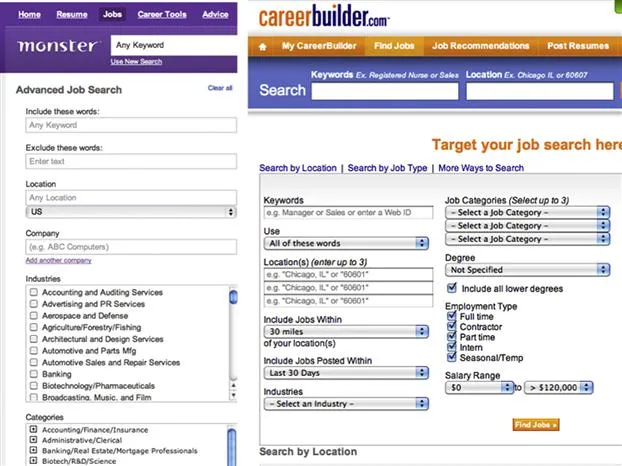

Consider a very different kind of example where data integration is also needed. Suppose you are searching for a new job, and you’d like to take advantage of resources on the Web. There are thousands of Web sites with databases of jobs (see Figure 1.3 for two examples). In each of these sites, you’d typically see a form that requires you to fill out a few fields (e.g., job title, geographical location of employer, desired salary level) and will show you job postings that are relevant to your query. Unfortunately, each form asks for a slightly different set of attributes. While the Monster form on the left of Figure 1.3 asks for job-related keywords, location, company, industry, and job category, the CareerBuilder form on the right allows you to select a location and job category from a menu of options and lets you further specify your salary range.

Figure 1.3 Examples of different forms on the Web for locating jobs. Note that the forms differ on the fields they request and formats they use.

Consequently, going to more than a handful of such Web sites is tiresome, especially if you’re doing this on a daily basis to keep up with new job postings. Ideally, you would go to a single Web site to pose your query and have that site integrate data from all relevant sites on the Web.

More generally, the Web contains millions of databases, some of which are embedded in Web pages and others that can be accessed through Web forms. They contain data in a plethora of domains, ranging from items typically found in classified ads and products to data about art, politics, and public records. Leveraging this incredible collection of data raises several significant challenges. First, we face the challenge of schema heterogeneity, but on a much larger scale: millions of tables created by independent authors and in over 100 languages. Second, extracting the data is quite difficult. In the case of data residing behind forms (typically referred to as the Deep Web or Invisible Web ) we need to either crawl through the forms intelligently or be able to pose well-formed queries at run time. For data that are embedded in Web pages, extracting the tables from the surrounding text and determining its schema is challenging. Of course, data on the Web are often dirty, out of date, and even contradictory. Hence, obtaining answers from these sources requires a different approach to ranking and data combination.

While the above two examples illustrate common data integration scenarios, it is important to emphasize that the problem of data integration is pervasive. Data integration is a key challenge for the advancement of science in fields such as biology, ecosystems, and water management, where groups of scientists are independently collecting data and trying to collaborate with one another. Data integration is a challenge for governments who want their different agencies to be better coordinated. And lastly, mash-ups are now a popular paradigm for visualizing information on the Web, and underlying every mash-up is the need to integrate data from multiple disparate sources.