- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Newnes Guide to Digital TV

About this book

The second edition has been updated with all the key developments of the past three years, and includes new and expanded sections on digital video interfaces, DSP, DVD, video servers, automation systems, HDTV, 8-VSB modulation and the ATSC system. Richard Brice has worked as a senior design engineer in several of Europe's top broadcast equipment companies and has his own music production company.

- A uniquely concise and readable guide to the technology of digital television

- New edition includes more information on HDTV (high definition) and ATSC (Advanced Television Systems Committe) - the body that drew up the standards for Digital Television in the U.S.

- Written by an engineer for engineers, technicians and technical staff

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Newnes Guide to Digital TV by Richard Brice in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

21

Introduction

Digital television

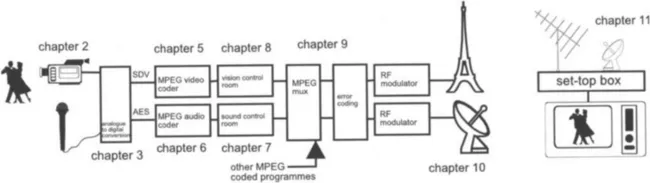

Digital television is finally here … today! In fact, as the DVB organization puts it on their web site, put up a satellite dish in any of the world’s major cities and you will receive a digital TV (DTV) signal. Sixty years after the introduction of analogue television, and 30 years after the introduction of colour, television is finally undergoing the long-predicted transformation – from analogue to digital. But what exactly does digital television mean to you and me? What will viewers expect? What will we need to know as technicians and engineers in this new digital world? This book aims to answer these questions. For how and where, refer to Figure 1.1 – the Newnes Guide to Digital Television route map. But firstly, why digital?

Figure 1.1 Guide to Digital Television – Route map

Why digital?

I like to think of the gradual replacement of analogue systems with digital alternatives as a slice of ancient history repeating itself. When the ancient Greeks – under Alexander the Great – took control of Egypt, the Greek language replaced Ancient Egyptian and the knowledge of how to write and read hieroglyphs was gradually lost. Only in 1799 – after a period of 2000 years – was the key to deciphering this ancient written language found following the discovery of the Rosetta stone. Why was this knowledge lost? Probably because Greek writing was based on a written alphabet – a limited number of symbols doing duty for a whole language. Far better, then, than the seven hundred representational signs of Ancient Egyptian writing. Any analogue system is a representational system – a wavy current represents a wavy sound pressure and so on. Hieroglyphic electronics if you like! The handling and processing of continuous time-variable signals (like audio and video waveforms) in digital form has all the advantages of a precise symbolic code (an alphabet) over an older approximate representational code (hieroglyphs). This is because, once represented by a limited number of abstract symbols, a previously undefended signal may be protected by sending special codes, so that the digital decoder can work out when errors have occurred. For example, if an analogue television signal is contaminated by impulsive interference from a motorcar ignition, the impulses (in the form of white and black dots) will appear on the screen. This is inevitable, because the analogue television receiver cannot ‘know’ what is wanted modulation and what is not. A digital television can sort the impulsive interference from wanted signal. As television consumers, we therefore expect our digital televisions to produce better, sharper and less noisy pictures than we have come to expect from analogue models. (Basic digital concepts and techniques are discussed in Chapter 3; digital signal processing is covered in Chapter 4.)

More channels

So far, so good, but until very recently there was a down side to digital audio and video signals, and this was the considerably greater capacity, or bandwidth, demanded by digital storage and transmission systems compared with their analogue counterparts. This led to widespread pessimism during the 1980s about the possibility of delivering digital television to the home, and the consequent development of advanced analogue television systems such as MAC and PALplus. However, the disadvantage of greater bandwidth demands has been overcome by enormous advances in data compression techniques, which make better use of smaller bandwidths. In a very short period of time these techniques have rendered analogue television obsolescent. It’s no exaggeration to say that the technology that underpins digital television is data compression or source coding techniques, which is why this features heavily in the pages that follow. An understanding of these techniques is absolutely crucial for anyone technical working in television today. Incredibly, data compression techniques have become so good that it’s now possible to put many digital channels in the bandwidth occupied by one analogue channel; good news for viewers, engineers and technicians alike as more opportunities arise within and without our industry.

Wide-screen pictures

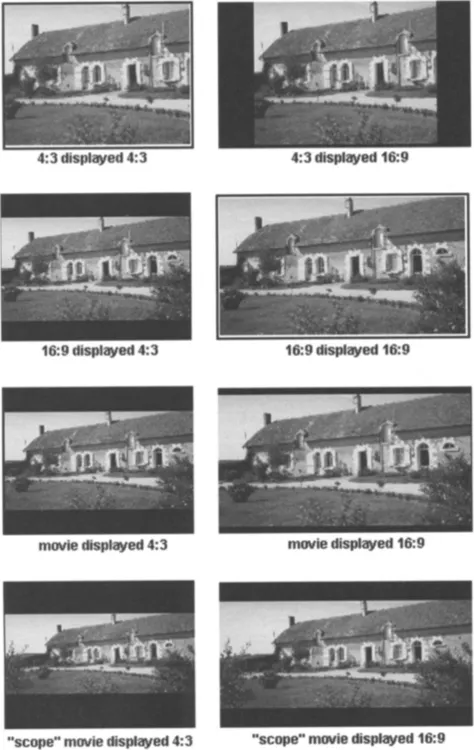

The original aspect ratio (the ratio of picture width to height) for the motion picture industry was 4:3. According to historical accounts, this shape was decided somewhat arbitrarily by Thomas Edison while working with George Eastman on the first motion picture film stocks. The 4:3 shape they worked with became the standard as the motion picture business grew. Today, it is referred to as the ‘Academy Standard’ aspect ratio. When the first experiments with broadcast television occurred in the 1930s, the 4:3 ratio was used because of historical precedent. In cinema, 4:3 formatted images persisted until the early 1950s, at which point Hollywood studios began to release ‘wide-screen’ movies. Today, the two most prevalent film formats are 1.85:1 and 2.35:1. The latter is sometimes referred to as ‘Cinemascope’ or ‘Scope’. This presents a problem when viewing wide-screen cinema releases on a 4:3 television. In the UK and in America, a technique known as ‘pan and scan’ is used, which involves cropping the picture. The alternative, known as ‘letter-boxing’, presents the full cinema picture with black bands across the top and bottom of the screen. Digital television systems all provide for a wide-screen format, in order to make viewing film releases (and certain programmes – especially sport) more enjoyable. Note that digital television services don’t have to be wide-screen, only that the standards allow for that option. Television has decided on an intermediate wide-screen format known as 16:9 (1.78:1) aspect ratio. Figure 1.2 illustrates the various film and TV formats displayed on 4:3 and 16:9 TV sets. Broadcasters are expected to produce more and more digital 16:9 programming. Issues affecting studio technicians and engineers are covered in Chapters 7 and 8.

Figure 1.2 Different aspect ratios displayed 4:3 and 16:9

‘Cinema’ sound

To complement the wide-screen cinema experience, digital television also delivers ‘cinema sound’; involving, surrounding and bone-rattling! For so long the ‘Cinderella’ of television, and confined to a 5-cm loudspeaker at the rear of the TV cabinet, sound quality has now become one of the strongest selling points of a modern television. Oddly, it is in the sound coding domain (and not the picture coding) that the largest differences lie between the European digital system and the American incarnation. The European DVB project opted to utilize the MPEG sound coding method, whereas the American infrastructure uses the AC-3 system due to Dolby Laboratories. For completeness, both of these are described in the chapters that follow; you will see that they possess many more similarities than differences: Each provides for multi-channel sound and for associated sound services; like simultaneous dialogue in alternate languages. But more channels mean more bandwidth, and that implies compression will be necessary in order not to overload our delivery medium. This is indeed the case, and audio compression techniques (for both MPEG and AC-3) are fully discussed in Chapter 6.

Associated services

Digital television is designed for a twenty-first century view of entertainment; a multi-channel, multi-delivery mode, a multimedia experience.

Such a complex environment means not only will viewers need help navigating between channels, but the equipment itself will also require data on what sort of service it must deliver: In the DTV standards, user-definable fields in the MPEG-II bitstream are used to deliver service information (SI) to the receiver. This information is used by the receiver to adjust its internal configuration to suit the received service, and can also be used by the broadcaster or service provider as the basis of an electronic programme guide (EPG) – a sort of electronic Radio Times! There is no limit to the sophistication of an EPG in the DVB standards; many broadcasters propose sending this information in the form of HTML pages to be parsed by an HTML browser incorporated in the set-top box. Both the structure of the MPEG multiplex and the incorporation of different types of data are covered extensively in Chapter 9.

This ‘convergence’ between different digital media is great, but it requires some degree of standardization of both signals and the interfaces between different systems. This issue is addressed in the DTV world as the degree of ‘interoperability’ that a DTV signal possesses as it makes the ‘hops’ from one medium to another. These hops must not cause delays or loss of picture and sound quality, as discussed in Chapter 10.

Conditional access

Clearly, someone has to pay for all this technology! True to their birth in the centralist milieu of the 1930s, vast, monolithic public analogue television services were nurtured in an environment of nationally instituted levies or taxes; a model that cannot hope to continue in the eclectic, diversified, channel-zapping, competitive world of today. For this reason, all DTV systems include mechanisms for ‘conditional access’, which is seen as vital to the healthy growth of digital TV. These issues too are covered in the pages that follow.

Transmission techniques

Sadly, perhaps, just as national boundaries produced differing analogue systems, not all digital television signals are exactly alike. All current and proposed DTV systems use the global MPEG-II standard for image coding; however, not only is the sound-coding different, as we have seen, but the RF modulation techniques are different as well, as we shall see in detail in later chapters.

Receiver technology

One phenomenon alone is making digital TV a success; not the politics, the studio or transmission technology, but the public who are buying the receivers – in incredible numbers! A survey of digital television would be woefully incomplete without a chapter devoted to receiver and set-top box technology as well as to digital versatile disc (DVD), which is ousting the long-treasured VHS machine and bringing digital films into increasing numbers of homes.

The future …

One experience is widespread in the engineering community associated with television in all its guises; that of being astonished by the rate of change within our industry in a very short period of time. Technology that has remained essentially the same for 30 years is suddenly obsolete, and a great many technicians and engineers are awar...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface to the second edition

- Preface to the first edition

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Foundations of television

- Chapter 3: Digital video and audio coding

- Chapter 4: Digital signal processing

- Chapter 5: Video data compression

- Chapter 6: Audio data compression

- Chapter 7: Digital audio production

- Chapter 8: Digital video production

- Chapter 9: The MPEG multiplex

- Chapter 10: Broadcasting digital video

- Chapter 11: Consumer digital technology

- Chapter 12: The future

- Index