![]()

Chapter 1 A Brief History of the Web

Since its inception in the early 1990s, the Web has revolutionized our lives and world more than many other technological developments in recent history. In this first chapter, we tour the history of the Web, during which we will identify three major streams of development and impact:

The

application stream is simply an account of what we have experienced over the past ten to fifteen years, namely the Web as an ever-growing and omnipresent library of information that we access through search engines and portals, the Web as a commerce platform through which people and companies do major portions of their business, and the Web as a media repository that keeps lots of things around for free.

The

technology stream touches upon the technological advances underneath the Web that have enabled its evolution and development (and which actually keep evolving). We keep this stream, which looks at both hardware and software, short in this chapter and elaborate more on it in

Chapter 2.

The

user participation and contribution stream looks at how people perceive and use the Web and how this has changed over the past fifteen years in some considerable ways. Since fifteen years is roughly half a generation, it will not come as a surprise that, especially, the younger generation today deals and interacts with the Web in an entirely different way than people did when it all started.

Taking these streams, their impacts, and their results together, we arrive at what is currently considered Web 2.0. By the end of the chapter, we try to answer questions such as: Is “Web 2.0” just a term describing what is currently considered cool on the Web? Does it only describe currently popular Web sites? Does it denote a new class of business models for the Web? Or does it stand for a collection of new concepts in information exchange over the Web? To say it right away, the point is that Web 2.0 is not a new invention of some clever business people, but it is the most recent consequence and result of a development that started more than ten years ago. Indeed, we identify three major dimensions along which the Web in its 2.0 version is evolving – data, functionality, and socialization – and we use these dimensions as an orientation throughout the remainder of this book. Please refer to O’Reilly (2005) for one of the main sources that has triggered the discussion to which we are contributing.

1.1 A new breed of applications: the rise of the Web

Imagine back in 1993, when the World Wide Web, the WWW, or the Web as we have generally come to call it, had just arrived; see Berners-Lee (2000) for an account. Especially in academia, where people had been using the Internet since the late 1970s and early 1980s in various ways and for various purposes including file transfer and e-mail, it quickly became known that there was a new service around on the Internet. Using this new service, one could request a file written in a language called HTML (the Hypertext Markup Language, see text following). With a program called a browser installed on his or her local machine, that HTML file could be rendered or displayed when it arrived. Let’s start our tour through the history of the Web by taking a brief look at browsers and what they are about.

1.1.1 The arrival of the browser

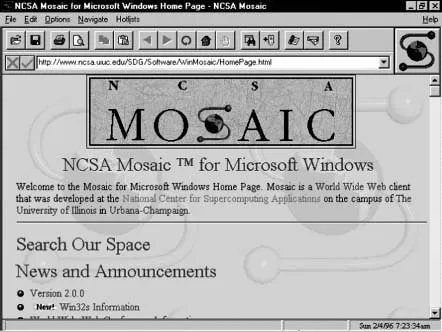

NCSA Mosaic

An early browser was Mosaic, developed by the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign in the United States. There had been earlier browser developments (e.g., Silversmith), but Mosaic was the first graphical browser that could display more than just plain ASCII text (which is what a text-based browser does). The first version of Mosaic had, among others, the following capabilities: It could access document and data using the Web, the File Transfer Protocol (FTP), or several other Internet services; it could display HTML files comprising text, anchors, images (in different formats), and already supported several video formats as well as Postscript; it came with a toolbar that had shortcut buttons; it maintained a local history as well as a hotlist, and it allowed the user to set preferences for window size, fonts, and so on. Figure 1.1 shows a screenshot of the Mosaic for Windows home page.

Mosaic already had basic browser functionality and features that we have gotten used to, and it worked in a way we are still using browsers today: the client/server principle applied to the Internet.

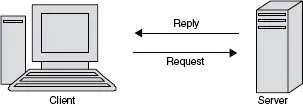

The client/server principle

The client/server principle is based on a pretty simple idea, illustrated in Figure 1.2. Interactions between software systems are broken down into two roles: Clients are requesting services, servers are providing them. When a client wants a service such as a database access or a print function to be executed on its behalf, it sends a corresponding request to the respective server. The server will then process this request (i.e., execute the access or the printing) and will eventually send a reply back to the client.

This simple scheme, described in more detail, for example, in Tanenbaum and van Steen (2007), has become extremely successful in software applications, and it is this scheme that interactions between a browser and a Web server are based upon. A common feature of this principle is that it often operates in a synchronous fashion: While a server is responding to the request of a client, the client will typically sit idle and wait for the reply. Only when the reply has arrived will the client continue whatever it was doing before sending off the request. This form of interaction is often necessary. For example, if the client is executing a part of a workflow that needs data from a remote database, this part cannot be completed before that data has arrived. It has also been common in the context of the Web until recently; we elaborate more on this in Chapter 2.

In a larger network, clients may need help in finding servers that can provide a particular service; a similar situation occurs after the initial setup of a network or when a new client gets connected. Without going into details, this problem has been solved in a variety of ways. For example, there could be a directory service in which clients can look up services, or there might be a broker to which a client has to talk first and who will provide the address of a server. Another option, also useful for a number of other issues arising in a computer network (e.g., routing, congestion control, consistent transaction termination), is to designate a central site as the network monitor; this site would then have all the knowledge needed in the network. An obvious drawback is that the network can hardly continue to function when the central site is down, a disadvantage avoided by peer-to-peer networks as shown in the following discussion.

HTML and HTTP

The basics that led to launching the Web as a service sitting atop the Internet were two quickly emerging standards: HTML, the Hypertext Markup Language, and HTTP, the Hypertext Transfer Protocol. The former is a language, developed by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN, the European particle physics lab in Geneva, Switzerland, for describing Web pages (i.e., documents a Web server will store and a browser will render). HTML is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. HTTP is a protocol for getting a request for a page from a client to a Web server and for getting the requested page in a reply back to the browser. Thus, the client/server principle is also fundamental for the interactions happening on the Web between browsers and Web servers, and, as we will see, this picture has only slightly changed since the arrival of Web services. Over the years, HTML has become very successful as a tool to put information on the Web that can be employed even without a deep understanding of programming. The reasons for this include the fact that HTML is a vastly fault-tolerant language, where programming errors are simply ignored, and that numerous tools are available for writing HTML documents, from simple text editor to sophisticated WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) environments.

Netscape

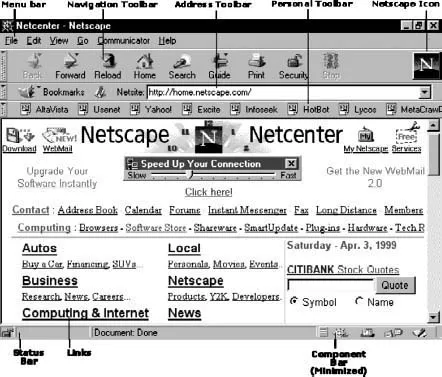

The initial version of Mosaic was launched in March 1993, and its final version in November the same year. Although far from modern browser functionality, with all their plug-ins and extensions (such as, for example, Version 2 of the Mozilla Firefox browser published in the fall of 2006 or Version 7 of the Internet Explorer), users pretty soon started to recognize that there was a new animal out there to easily reach for information that was stored in remote places. A number of other browsers followed, in particular Netscape Navigator (later renamed Communicator, then renamed back to Netscape) in October 1994 and Microsoft Internet Explorer in August 1995. These two soon got into what is now known as the browser war, which, between the two, was won by Microsoft but which is still continuing between Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Mozilla Firefox.

In mid-1994, Silicon Graphics founder Jim Clark started to collaborate with Marc Andreessen to found Mosaic Communications (later renamed Netscape Communications). Andreessen had just graduated from the University of Illinois, where he had been the leader of the Mosaic project. They both saw the great potential for Web browsing software, and from the beginning, Netscape was a big success (with more than 80 percent market share at times), in particular since the software was free for noncommercial use and came with attractive licensing schemes for other uses. Netscape’s success was also due to the fact that it introduced a number of innovative features over the years, among them the on-the-fly displaying of Web pages while they were still being loaded; in other words, text and images started appearing on the screen already during a download. Earlier browsers did not display a page until everything that was included had been loaded, which had the effect that users might have to stare at an empty page for several minutes and which caused people to speak of the “World-Wide Wait.” With Netscape, however, a user could begin reading a page even before its entire contents was available, which greatly enhanced the acceptance of this new medium. Netscape also introduced other new features (including cookies, frames, and, later, JavaScript programming), some of which eventually became open standards through bodies such as the W3C, the World Wide Web Consortium (w3.org), and ECMA, the European Computer Manufacturers Association (now called Ecma International, see www.ecma-international.org).

Figure 1.3 shows Version 4 of the Netscape browser, pointed to the Netscape home page of April 1999. It also explains the main features to be found in Netscape, such as the menu bar, the navigation, address, and personal toolbars, the status bar, or the component bar.

Although free as a product for private use, Netscape’s success was big enough to encourage Clark and Andreessen to take Netscape Communications public in August 1995. As Dan Gillmor wrote in August 2005 in his blog, then at Bayosphere (bayosphere.com/blog/dangillmor/080905/netscape):

I remember the day well. Everyone was agog at the way the stock price soared. I mean, this was a company with scant revenues and no hint of profits. That became a familiar concept as the decade progressed. The Netscape IPO was, for practical purposes, the Big Bang of the Internet stock bubble – or, to use a different metaphor, the launching pad for the outrages and excesses of the late 1990s and their fallout… . Netscape exemplified everything about the era. It launched with hardly any revenues, though it did start showing serious revenues and had genuine prospects …

1.1.2 The flattening of the world

Let’s deviate from the core topic of this section,...