- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Internal Combustion Engines

About this book

Internal Combustion Engines covers the trends in passenger car engine design and technology. This book is organized into seven chapters that focus on the importance of the in-cylinder fluid mechanics as the controlling parameter of combustion. After briefly dealing with a historical overview of the various phases of automotive industry, the book goes on discussing the underlying principles of operation of the gasoline, diesel, and turbocharged engines; the consequences in terms of performance, economy, and pollutant emission; and of the means available for further development and improvement. A chapter focuses on the automotive fuels of the various types of engines. Recent developments in both the experimental and computational fronts and the application of available research methods on engine design, as well as the trends in engine technology, are presented in the concluding chapters. This book is an ideal compact reference for automotive researchers and engineers and graduate engineering students.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Introduction

M.L. MONAGHAN, Ricardo Consulting Engineers plc, Bridge Works, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex BN4 5FG, UK

Publisher Summary

This chapter outlines the underlying principles of operation of an engine, the consequences in terms of performance, economy and pollutant emission, and the means available for further development and improvement. The internal combustion engine is widely used in applications ranging from marine propulsion to generating powers in small hand-held tools. Car passenger engine is a lightweight engine with compact fuel storage. The chapter also discusses the spread of passenger car engines. Automobiles have huge impact on the energy use of most industrialized countries because the fuel taxes are a major source of government revenue. Its impact on the fossil fuel reserves of the world is such that major swings in national energy policy extending to changes in the use of nuclear power, and the amount of coal mined and burnt are involved. The magnitude of its use of oil means that environmental pollution ranging from relatively local air quality problems to consideration of the “greenhouse effect” on the global climate has large influence on the total design of the car and most particularly, the design, the construction and the operation of the engine.

I. The passenger car engine

II. The birth of the internal combustion engine

III. The concept of the passenger car engine

IV. The spread of the passenger car industry

V. The pressures on the engine

A. Survival in service

B. Improved power and economy via the fuel

C. Improved power and economy via the engine

D. Cost reductions

E. Requirement for better economy — early diesels

F. Variety and experiment

G. Environmental pressures

H. Oil crises and energy conservation

I. More refinement and power

J. Electronics

K. The future

I. The passenger car engine

The internal combustion engine is the dominant prime mover in our society and it is used in applications ranging from marine propulsion and generating sets in powers of nearly 100 MW to hand-held tools where the power delivered can be as little as 100 W. The former requires the use of large, slow-speed diesels with cylinder bores of around 1000 mm while the latter normally involves the use of gasoline-fuelled, two-strokes with cylinder bores around 20 mm. Within these two extremes lie medium speed diesel engines, heavy automotive diesel engines, aircraft engines, engines for passenger cars and motorcycles and small industrial engines — a complete study of the internal combustion engine would require many volumes. For this book, the decision was taken to concentrate on the passenger car engine. The sheer number of passenger car engines produced and the influence the car has had (and will continue to have) on our social and economic life means that the passenger car engine is often considered as synonymous with “internal combustion engine”. The volume of research into the passenger car engine ensures that much published literature deals with that engine, and the serious student of the internal combustion engine will invariably need to place a knowledge of the passenger car engine at the core of his studies.

II. The birth of the internal combustion engine

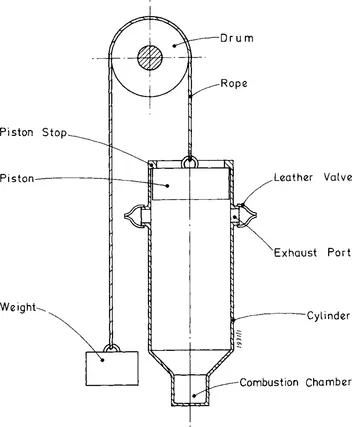

The origin of the concept of the “internal combustion engine” is probably impossible to trace, but it seems that the experiments of Christiaan Huygens (the Dutch mathematician, physicist and astronomer, perhaps better known for his work in astronomy and horology) with gunpowder “engines” in the early seventeenth century were the first indications that anyone had approached a working engine. The experiments were recorded in a letter he wrote to his brother in 1673 and in which he described a gunpower-fired cylinder which raised weights (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Huygen’s gunpowder engine.

The cylinder, closed by a “free” piston, had a combustion chamber at its lower end and the charge of gunpowder and air resided in this chamber. On ignition the piston flew to the top of the cylinder uncovering exhaust ports which allowed the heated gases to escape. The piston then fell back partly under its own weight and partly due to the cooling of the residual gases. The descent of the piston was arranged to raise weights by pulling a rope round a drum.

For almost 200 years after the experiments of Huygens prime movers were “external combustion engines” such as steam engines and hot air engines. The technology and thinking of power plant engineers was dominated by the concepts required for the production and operation of these engines. By the 1860s, however, the industry had become sufficiently mature to establish the conditions for the emergence of the passenger car engine.

Lenoir’s non-compressing gas engine of 1860 was the first production internal combustion engine. Its manufacture in France, Germany, England and even the USA signalled the commercial awareness which would facilitate international licensing arrangements and the same awareness would spur the moves towards mobile power plants. Engineers began to experiment with a wide variety of fuels and engine concepts. The understanding was such that Beau de Rochas was able to file (but not publish) his “four-stroke” patent and competition and interest promoted such exhibitions as the “International Exposition” in Paris of 1867.

It was at that 1867 exhibition that Otto and Langen exhibited their atmospheric gas engine which demonstrated so convincingly the efficiency advantages to be obtained from a high expansion ratio. Orthodoxy at that time had adopted the piston crank mechanism so well proven in steam engine service but the Otto and Langen engine reverted to the free piston principle of Huygens and it was this which permitted the high expansion ratio. Like Huygens’s engine, a vertical cylinder was used to guide the piston and the power was extracted on the descending stroke of the piston. The power takeoff was through an overrunning clutch driving a flywheel rather than the rope and drum system of Huygens. Otto and Langen’s engine was so successful that licences were granted to producers in virtually every industrialized country and almost 3000 had been made by 1880. The significance of this can be judged against the usual “production” volumes of 10 or 20 at that time.

The next real step came with Otto’s four-stroke engine of 1876. It was at least 25% more efficient than the atmospheric engine, had less than a tenth the swept volume and ran at least twice as fast. It would also be recognized by any modern engineer since it had a piston crank mechanism, flywheel and positively actuated inlet and exhaust valves. Like the atmospheric engine the model “A” from the Deutz company, as Otto’s company had now become, set a world standard and licences were again negotiated world-wide. The engine was produced in tens of thousands and its very success provoked the challenges to the four-stroke patent which led to the collapse of Otto’s case in 1886 and the recognition of the insight of Beau de Rochas. By this time the internal combustion engine industry had become firmly established and many engineers were sufficiently knowledgeable to take advantage of the release from the Otto patent.

III. The concept of the passenger car engine

The engine is the key to the achievement of a viable passenger car and although Cugnot’s steam-powered gun carriage of 1769 and even Siegfried Marcus’s gas-engine driven carriage demonstrated in Vienna in 1875 had shown that powered vehicles were feasible, it required the concept of a light–weight engine with compact fuel storage (liquid) to obtain a true passenger car. That is a vehicle which can be used by the general population for all purposes from business through domestic and pleasure to sport.

In 1882 three engineers who had grasped that engine concept set the foundations of the passenger car industry. Those engineers were Gottlieb Daimler (1834–1900), Wilhelm Maybach (1846–1929) and Karl Benz (1844–1929).

Daimler, who had been Technical Director at the Deutz works, left in that year and was joined by Maybach also from Deutz. Together they set out to develop a range of high speed, lightweight engines. They brought expertise in four-stroke engines, surface carburettors and hot tube ignition systems from their old factory, and from their general design of “Standuhr” engine they evolved the variant which powered their first car in 1886.

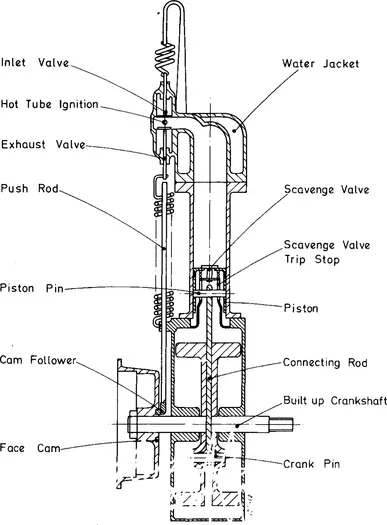

The engine (see Figure 2 for main features) was 70 mm bore by 100 mm stroke and developed just over 1 hp at 650 rev min–1. It weighed around 100 kg. The name “Standuhr” derived from the resemblance of the engine to an upright clock and, although multi-cylinder models were eventually produced for many applications to the general “Standuhr” design, the details differed in many respects from modern engines and even the engines developed in the next few years by other engineers. The most significant differences were in the areas of valve operation and scavenging.

Figure 2 Daimler 1886 “Standuhr” engine.

The inlet valve was “automatic”, being operated by intake depression as became standard for a short time, but the exhaust valve was operated by a “face-cam” machined in the flywheel face. Most contemporary engines used cams and tappets in a similar manner to modern engines or copied steam engine practice with eccentrics or slide-valves. By 1893 the successor to the “Standuhr”, the “Phoenix” had fallen into line with convention and used a normal camshaft driven by gears — this arrangement carried the extra weight and cost of a pair of gears but it made governing (via the exhaust valve) much simpler.

Perhaps the most radical departure from convention was the inclusion of the “scavenge valve” in the piston. This was added to provide a positive exhaust action and avoid infringement of the apparently valid Otto patent. The crankcase of the “Standuhr” engine was well filled by packing pieces on the crank cheeks and this permitted significant crankcase compression. As the piston approached bottom dead centre, the scavenge valve was tripped open by a stop located from the crankcase and this permitted the compressed crankcase air to pass up into the cylinder and assist in the expulsion of the residual gases. In fact, valve timing and porting expertise at that time was such that most engines were quite poorly scavenged and this feature actually gave a significant advantage in performance.

It was the “Standuhr” engine which powered the first Daimler car in 1886.

The third engineer, Karl Benz, founded his “Gasmotorenfabrik in Mannheim” (G. F. M.) in 1881. By 1886 he had developed electric ignition and a simple surface carburettor, with float control of fuel level, to the point where he could contemplate modifying one of his gas engines to burn liquid fuel and install it in a vehicle. The engine he used was 90 mm bore by 120 mm stroke and, like Daimler’s, used the four-stroke cycle. It ran at 250–300 rev min–1 producing about 0.5 hp.

Altho...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Combustion Treatise

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Dedication

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Gasoline Engines

- Chapter 3: Diesel Engines

- Chapter 4: Turbocharged Engines

- Chapter 5: Automotive fuels

- Chapter 6: Recent research developments and their application to engine design

- Chapter 7: Future trends in engine technology

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Internal Combustion Engines by Constantine Arcoumanis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Engineering General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.