Abstract

This introductory chapter provides a historical introduction to quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and quantitative real-time PCR. We outline the development of standard, real-time and reverse-transcriptase PCR, highlight the technical difficulties that hindered their conversion into quantitative techniques, describe how these obstacles have been overcome, and point out some of the remaining problems and recent developments. The topics presented include: theoretical versus actual results, specimen collection and transport, nucleic acid extraction, optimization, inhibitors, contamination, detection, competitive PCR, real-time PCR, and reverse-transcriptase real-time PCR.

Introduction

As soon as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was described by Mullis and coworkers in the mid-1980s (Mullis et al., 1986; Mullis & Faloona, 1987), people began to imagine using it as a tool for the quantitation of small numbers of nucleic acid molecules. Its potential utility in monitoring the number of virus genomes present in various acute and chronic infections, in monitoring residual disease after cancer chemotherapy, and in measuring messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis after treating cells with various inducers and/or cytokines, and even in measuring microorganisms in water, was immediately obvious, although these goals were originally unattainable. The extraordinary sensitivity of PCR was one of the main problems that made it so challenging to transform from a qualitative to a quantitative technique. A few molecules of contaminating target sequence could affect quantitation. Anything that interfered with the exponential amplification occurring in the first few cycles of amplification would interfere with the ultimate quantitative result. And furthermore, Northern and Southern blots, the “gold standard” techniques were, in general, so much less sensitive than PCR that it was difficult to know how to determine whether one had achieved accurate quantitation. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was thought by many that the goal of quantitative PCR would remain unattainable. In fact, as pointed out by Ferre (1992), the first two books on PCR technology had no mention of quantitation (Ehrlich, 1989; Ehrlich et al., 1989).

Before quantitative PCR became feasible, many problems had to be overcome: older techniques were refined, and new ones invented. The first major breakthrough was the change from the heat-labile Klenow fragment of the E. coli pol-1 DNA polymerase; which had to be added at each cycle, to the heat-stable polymerase (Taq) previously isolated from Thermus aquaticus (Chien, Edgar, & Trela, Ehrlich et al., 1976; Crescenzi et al., 1988). This has served as the basis or comparator of PCR ever since (Saiki et al. 1988). Twenty years ago, in what should be recognized as a classic paper in the history of quantitative PCR, Alice Huang and coworkers (1989) demonstrated that both relative and absolute quantitation were possible. Even then, the transformation of quantitative techniques from something possible under ideal conditions in a research laboratory into something rapid and robust enough to be performed as a routine diagnostic test took years. In the United States, the first commercially available, PCR-based, quantitative nucleic acid detection assay was the Roche Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor assay, version 1.0, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1996. It had a lower limit of quantitation of 400 copies/ml. This has now been reduced to 48 (Cobas TaqMan) or 40 (Abbot RealTime), and is projected to go even lower. Below 10 copies/reaction, the stochastic properties of the reaction cause difficulties in calculation.

By 2009, most major technical problems have been resolved. The techniques have become automated and robust enough that quantitative PCR assays for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B and C viruses are routine, commercially available laboratory test performed daily in large clinical laboratories. Even today, when HIV viral load testing is used routinely as a surrogate end point for monitoring HIV antiretroviral therapy, things are not always as straightforward as one could wish. Different assays have different sensitivities and different abilities to detect different strains and subtypes of HIV (Damond et al., 2007; Holguin, et al.,2008). Some Abbott RealTime HIV-1 Assay kits were recently recalled by the FDA in the United States because they might under-quantitate HIV for low-titer samples (recall number B-0463-09 on FDA website, queried 2/25/2009).

Early successes at quantitative PCR represented triumphs over unwieldy technology. Conventional PCR has a detection step at the end of a fixed number of cycles of amplification. The linear range is narrow and depends on the number of cycles of amplification. For example, Kellogg, Sninsky, and Kwok (1990) and Kellogg et al. (1990) showed that the linear range for detection of a plasmid DNA in the presence of 1μgm of human DNA was 3,200–52,100 copies/ml with 20 cycles, from 200–3,200 copies/ml with 25 cycles, and from 12–400 copies/ml with 40 cycles. If many target sequences are present, the reactions all plateau at the same level. Furthermore, conventional detection requires extensive manipulation of the sample, which almost inevitably spreads amplifiable amplicons around the laboratory.

Perhaps the greatest step towards making quantitative PCR generally feasible was the development, in the late 1980s, of rapid-cycle PCR by Wittwer’s group at the Pathology Department at the University of Utah and at their technology spinoff company, Idaho Technologies, Inc. (Wittwer and Garling, 1990). In 1993, Higuchi, Fickler, Dollinger, and Watson (1993), at Roche first published a paper on real-time detection using ethidium bromide (EtBr) and a video recorder to monitor product synthesis. Idaho Technology’s Light Cycler was licensed to Roche in 1996. The explosion of scientific knowledge based on these and similar techniques continues today.

Long before real-time PCR was developed, many other steps had been taken with conventional PCR, which allowed real-time PCR to assume its promise almost as soon as the instrumentation became available. The factors influencing the quantitative ability of PCR are outlined later in this chapter. Because PCR and HIV diagnosis and testing grew up together, and because the virus has an RNA genome and makes DNA transcripts which integrate into the host cell, thus involving both PCR and reverse transcriptase PCR, we have tended to concentrate on the HIV-related literature. We have tried to highlight the historical influences, and then to segue quickly to the current state of affairs, showing that many of the historical problems remain relevant today.

Theoretical Versus Actual Results

In theory, the number of product molecules doubles at each cycle. Thus, for each copy of the target sequence present in the original reaction mix, after one cycle there would be two, after two cycles four, after three cycles eight, and so forth. The theoretical equation giving the number of copies (Cn) present at the end of

n cycles of replication is Cn = Co(1 + E)

n, where

Co is the amount of template present at the outset, and

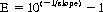

E is the efficiency of amplification. If the amplification is perfectly efficient, E = 1, and thus 1 + E = 2. In many situations, the amplification is not perfectly efficient. A 0.1 difference in efficiency leads to a fivefold difference in quantitation at the end of 30 cycles. Efficiency can be calculated using the following formula:

Slope refers to the slope of the line created by plotting the crossing threshold (Ct, see quantitation later in this chapter) values of a serial dilution of the target gene versus the logarithm of the gene concentration.

This equation also applies only in the early, exponential phase of the reaction, when no reagent is limiting. The efficiency at the beginning may be changed significantly by optimization, inhibitors, small tube-to-tube variations in temperature, and other unknown problems. The efficiency of amplification usually decreases during the reaction. It can be affected by enzyme inactivation and saturation, by product reannealing, and by competition between target amplification and the amplification of primer dimers and products of mispriming. In the 1980s, if the target concentration was low, the amounts of false products often exceeded those of the true product, or completely prevented its detection. Anything that affected the efficiency of the reaction during the early, exponential phase had a major effect on the number of product molecules made (see clementi et al., 1993).

All reactions with numerous targets saturate at roughly the same level, precluding determination of the initial starting concentration at the end of the reaction, except in a very narrow range of target molecule concentrations. Real-time PCR eliminated this problem by measuring the number of amplicons produced during each cycle.

Specimen Collection and Transport

Although it may not be intuitively obvious, specimen collection, transport, and storage procedures may have a significant effect on quantitative PCR results. RNA is easily degraded. Enveloped viruses are fragile. RNA within cells or degraded virions is more subject to degradation than DNA. So time and temperature of specimen transport, temperature of specimen storage, and freezing and thawing procedures may have a significant effect on the outcome of quantitation. And other, unpredictable factors may come into play.

Our previous experience with the Becton Dickenson Plasma Preparation Tubes for HIV viral load assays is instructive (Salimnia et al. 2005) These tubes were intended for transport of blood specimens from remote collection sites to central laboratory facilities. They are basically purple-topped tubes containing a thixotropic gel that allows cells to pass through during centrifugation of the specimen, while leaving cell-free plasma containing the virus above the gel. It was originally recommended that specimens be centrifuged and frozen in these tubes. Laboratories validated this procedure for HIV viral load determinations when viral load testing was relatively insensitive and the usual viral loads in HIV-positive individuals were high. When highly active antiretroviral therapy became the norm, and maintaining an undetectable viral load (then greater than 50 copies/ml) became the goal of therapy, we found that the procedure we were using gave spurious results. If the specimen was frozen in the tube, the viral load was often 102 to more than 103 copies/ml higher than that determined when the specimen was decanted after centrifugation and frozen in a separate tube. This alteration was not new: it had been occurring since the first specimen for the determination of HIV viral load was fro...