- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

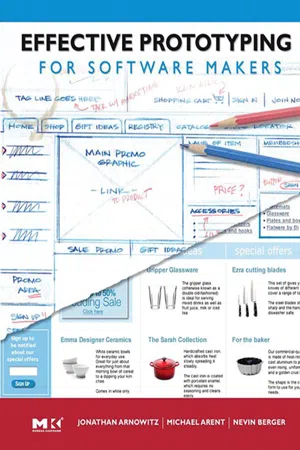

Effective Prototyping for Software Makers

About this book

Effective Prototyping for Software Makers is a practical, informative resource that will help anyone—whether or not one has artistic talent, access to special tools, or programming ability—to use good prototyping style, methods, and tools to build prototypes and manage for effective prototyping.

This book features a prototyping process with guidelines, templates, and worksheets; overviews and step-by-step guides for nine common prototyping techniques; an introduction with step-by-step guidelines to a variety of prototyping tools that do not require advanced artistic skills; templates and other resources used in the book available on the Web for reuse; clearly-explained concepts and guidelines; and full-color illustrations and examples from a wide variety of prototyping processes, methods, and tools.

This book is an ideal resource for usability professionals and interaction designers; software developers, web application designers, web designers, information architects, information and industrial designers.

* A prototyping process with guidelines, templates, and worksheets;* Overviews and step-by-step guides for 9 common prototyping techniques;* An introduction with step-by-step guidelines to a variety of prototyping tools that do not require advanced artistic skills;* Templates and other resources used in the book available on the Web for reuse;* Clearly-explained concepts and guidelines;* Full-color illustrations, and examples from a wide variety of prototyping processes, methods, and tools. * www.mkp.com/prototyping

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1 WHY PROTOTYPING?

WHAT IS A PROTOTYPE?

AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF PROTOTYPING

THE PURPOSE OF PROTOTYPING

SUMMARY

REFERENCES

For many of us, prototyping is essential to creating successful software and successful user experiences. Prototyping ensures success because of its clear depiction of software requirements: instead of describing requirements it visualizes them. If done correctly, prototyping allows us to experiment in the safety of a form which can be easily changed without much loss of time or wasted effort when compared to re-programming software. Done effectively, prototyping enables us to go beyond just meeting requirements, by enabling experimentation and exploration for the optimal solutions. Done carelessly, prototyping can just as easily create a murky stew of ideas lost in redundant versions, unarticulated assumptions, and competing visions. This book aims to explain what prototyping is, good reasons for prototyping, and how to effectively prototype.

WHAT IS A PROTOTYPE?

pro·to·type n. 1. An original or model after which anything is copied; the pattern of anything to be engraved, or otherwise copied, cast, or the like; a primary form; exemplar; archetype [Webster’s 1913 Dictionary].

pro·to·type n. 1. An original type, form, or instance serving as a basis or standard for later stages. 2. An original, full-scale, and usually working model of a new product or new version of an existing product. 3. An early, typical example [http://www.dictionary.com; accessed January 13, 2004].

The definition of prototype has changed little in more than 90 years. Webster’s 1913 Dictionary and today’s dictionary.com both classify a prototype in roughly the same way: as a model of a final product. Yet the new definition does make a subtle important difference. Unlike Webster’s, the definition from dictionary.com does make a slight change using the word stages-plural-illustrating the iterative nature of prototyping.

This book specifically covers prototyping software as described by Bill Verplank, who suggests that: “ ‘Prototyping’ is externalizing and making concrete a design idea for the purpose of evaluation” [Munoz 1992]. We like Verplank’s definition because prototypes are tangible software representations, which permit the software team to experience a design without needing to program the software.

A prototype is any attempt to realize any aspect of software content. For example, the prototype can be a realization of interaction and navigation from one point in a product to another. A prototype can also be a hierarchical schema of an information design, divorced from both the look and feel of the final software. Other aspects of a prototype include:

The current state of the art is a checkpoint of what the software would be like if it was built with just the currently existing knowledge of the software-making team.

Requirements can refer to business requirements, technical requirements, functional requirements, end-user requirements, or any combination thereof.

Content can be any of the different content types that make the prototype: information design, interaction design, visual design, editorial content, product branding, and system performance.

For the sake of brevity we refer to any human-computer interaction as software throughout this book, regardless of whether it is a product or service, whether desktop software, mobile software, website, web application/service, or other interactive digital product.

AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF PROTOTYPING

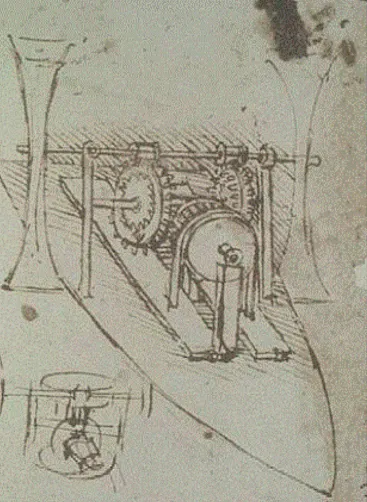

Software makers are not the first to wrestle with the challenges of inventing and prototyping technology. Historical perspectives help us understand the nature, challenges, and advantages of prototyping. Here we want to briefly explore three prototypers from the past: Leonardo da Vinci, Thomas Edison, and Henry Dreyfuss. Each has made remarkable contributions to design and the process of invention, and each has explored the possibilities of their inventions with prototypes.

Da Vinci left behind prototypes of concepts and ideas (in the form of drawings) that would take centuries to come to fruition. Thomas Edison used exhaustive prototyping as the engine that drove his inventive ideas. And Henry Dreyfuss used prototypes to make industrial products more user-centered and ergonomically sound. These three people illustrate how a prototype serves one primary purpose: the means of moving an idea from the human imagination to a form that other humans can readily see, understand, evaluate, use, and further develop.

FIGURE 1.1 A drawing of an inventive idea by Leonardo da Vinci.

“I have often thought that one of the industrial designer’s most valuable contributions to his client’s product is his ability to visualize. He can sit at a table and listen to executives, engineers, production and advertising men throw off suggestions and quickly incorporate them into a sketch that crystallizes their ideas–or shows their impracticability. His sketch is not, of course, a finished design, but the beginning is likely to be there.” Henry Dreyfuss, 1967

Leonardo da Vinci: The Thinking Man’s Inventor

The drawings of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) are some of the most fascinating examples of prototype usage for exploring innovation. During the late 15th century, da Vinci created detailed sketches of engineering ideas at the request of his patron, the Duke of Milan. These paper prototypes freed da Vinci from the contemporary constraints of what was possible to build. At liberty to push the limits as far as his imagination, da Vinci became one of history’s most profound and prolific inventors.

FIGURE 1.2 Leonardo da Vinci.

Da Vinci’s inventions would not be built for hundreds of years: flying machines, municipal construction, canals, buildings, and designs for advanced weapons.

Da Vinci’s paper prototypes, and the models that others built from them, serve as proofs of concept well in advance of the technology that would eventually enable their development. Its in the same way use of prototypes will serve as the proof of concept that starts software development in the right direction.

Thomas Alva Edison: Inventor Prototyper

Thomas Alva Edison (1847–1931) was one of the most prolific and eminent American inventors. He explored ideas through extensive prototyping both in paper and in physical models. Of 1,368 separate and distinct patents he earned during his lifetime, the most recognized are the phonograph and perfections to the electric light bulb. The bulk of Edison’s work was focused on creating mass-market products. He labored during a time of great industrial transition, with exciting developments in materials and production processes. Creating a prototype became not just as da Vinci used them as a source of innovation, but also as the means to communicate the manufacturing requirements: what parts were needed, what molds needed to be made, what the production costs would be, etc. These prototypes sought to improve life on a mass market level. Other American inventors in Edison’s time, such as Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922, inventor of the telephone), George Washington Carver (1864–1943, inventor of peanut agricultural sciences and food products), and John Wesley Hyatt (1837–1920, inventor of celluloid, an early thermoplastic), sought to improve daily life by reducing manual labor and introducing luxury items and entertainment to the masses.

FIGURE 1.3 Thomas Alva Edison.

Edison was a focused perfectionist. His models had to work consistently well because they were destined for mass production. “He would sit at one of the lab tables, chew on a wad of tobacco, and make a little drawing of a new component. He’d ponder it, pass it around among his staff, and wander off to read a couple of technical manuals. He would frown. He would spit a sluice of tobacco onto the floor, and commence to cogitate. He played with his stuff with the grace and zest of an artist, or a child. He would build a prototype and experiment with it for hours, days, weeks, months–whatever it took” [ipFrontline.com].

Edison was a tinker who believed in hard work. More scientist than philosopher, Edison’s perseverance and dedication to success earn him the distinction as a model of the prototyping approach, especially rapid prototyping for the creation of the successful design. “To assist him in his invention work, Edison employed a large and diverse staff of more than 200 machinists, scientists, craftsmen, and laborers at peak production. This staff was divided by Edison into as many as 10 to 20 small teams, each working simultaneously for as long as necessary to turn an idea into a perfected finished prototype or model. Edison himself would move from team to team advising and cajoling efforts as necessary. When a particular invention was perfected, Edison quickly patented the device. With such extensive facilities and his large staff, Edison was able to turn out new products on an unprecedented scale and with unprecedented speed” [National Park Service]. Edison’s iterative approach and use of multiple prototyping methods are still critical approaches to prototyping today, as witnessed by the successful use of rapid prototyping in successful software design.

Henry Dreyfuss: Designer Prototyper

Industrial designers of the last century have used prototyping and iterative design to articulate both the product’s and the end-user’s needs. Indeed, the struggles of industrial designer to gain acceptance into the engineering and manufacturing world resemble very closely the Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) professional’s struggles for acceptance in the world of software engineering. Henry Dreyfuss (1904–1972) was the archetype of industrial designers, not least because he left behind a body of literature detailing his efforts in prototyping. Dreyfuss used prototyping to couple the perspectives of user-centered design principles, business interests, and engineering. He saw prototyping as one of the most important contributions an industrial designer makes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- About the Authors

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Why Prototyping?

- Chapter 2: The Effective Prototyping Process

- Phase I: Plan Your Prototype

- Phase II: Specification of Prototyping

- Phase III: Design Your Prototype

- Phase IV: Results of Prototyping

- Glossary

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Effective Prototyping for Software Makers by Jonathan Arnowitz,Michael Arent,Nevin Berger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Human-Computer Interaction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.