![]()

Chapter 1

Database Discovery with Dynamic Queries

![]()

Introduction to Database Discovery with Dynamic Queries

Visual Information Seeking: Tight Coupling of Dynamic Query Filters with Starfield Displays

C. Ahlberg and B. Shneiderman

Dynamic Queries for Visual Information Seeking

Temporal, Geographical and Categorical Aggregations Viewed through Coordinated Displays: A Case Study with Highway Incident Data

A. Fredrikson, C. North, C. Plaisant, and B. Shneiderman

Broadening Access to Large Online Databases by Generalizing Query Previews

E. Tanin, C. Plaisant, and B. Shneiderman

Dynamic Queries and Brushing on Choropleth Maps

G. Dang, C. North, and B. Shneiderman

As yet I know of no person or group that is taking nearly adequate advantage of the graphical potentialities of the computer … In exploration they are going to be the data analyst’s greatest single resource.

John Tukey. “The Technical Tools of Statistics.”

American Statistician 19 (1965)

When users are confronted by a new and large database, they usually begin by trying to understand its schema, attributes, and attribute values, possibly by referring to data dictionaries. But understanding the extent of the data is often difficult-How many items are there? Which attribute values or patterns occur often or rarely? Where are the clusters, gaps, or outliers? Which attributes are correlated? These questions are very difficult to discover with existing tools. But the hardest task is to know which questions to ask in the first place.

The goal of designers of modem information visualization tools is to help users discover which questions to ask. These new tools enable users to gain an overview, explore rapidly, test hypotheses, and then share their results with colleagues.

One significant approach toward this end is called dynamic queries, a technique that enables interactive exploration. Dynamic queries allow users to update two-dimensional graphical displays in less than 100 milliseconds, even with databases of a million items. As users adjust sliders, buttons, check boxes, and other control widgets, the continuously visible display of results updates rapidly. There is no Submit button because users can select rapidly from the set of permissible attribute values. There are no syntax errors, and users feel they are in control. They can explore quickly, testing their hypotheses, finding outliers, and identifying patterns.

The appropriate visual display depends on the data—world maps, tree diagrams, tree maps, body diagrams, timelines, scatter plots, and more innovative ideas have all been used. Two of our early applications of dynamic queries were a chemical table of elements (1992 video*), and HomeFinder, a regional map of the Washington, D.C. area (91–11). As query widgets were changed, the chemical symbols changed color to signify inclusion and dots indicating homes for sale lit up on the regional map (92–01) (free downloadable version at www.cs.umd.edu/hcil/pubs/products.shtml).

Christopher Ahlberg, a visiting student from Sweden during the summer of 1991, took up Ben Shneiderman’s lunch-time challenge to work on dynamic query interfaces that applied the following direct manipulation principles (originally described in Shneiderman 1982):

Continuous representation of the objects and actions of interest with meaningful visual metaphors

Physical actions or presses of labeled buttons, instead of complex syntax

Rapid, incremental, and reversible operations whose effect on the object of interest is visible immediately

When used appropriately, these principles can lead to designs that have these beneficial features.

Novices learn quickly, usually through a demonstration by a more experienced user.

Experts work rapidly to carry out a wide range of tasks, even defining new functions and features.

Knowledgeable intermittent users can retain the operating concepts.

Error messages are rarely needed because only permissible values are selectable.

Reversible actions reduce anxiety.

Users gain confidence and mastery because they are the initiators of action, they feel in control, and they can predict the system responses.

Christopher’s first overnight success was making a modern slider-based version of a polynomial viewer first built in 1972 (Shneiderman 1974). As users move the sliders for each coefficient, the curve gracefully reshapes on the screen, creating dancing parabolas. Within a week, he had satisfied a second challenge of a dynamic query interface for the chemical table of elements. He put up the periodic table with chemical symbols in red with six sliders for attributes such as atomic radius, ionization energy, and electronegativity. As users move the sliders, the chemical symbols change to red showing the clusters, jumps, and gaps that chemists find fascinating. A study with 18 chemistry students showed faster performance with use of a visual display (versus a simple textual list) and a visual input device (versus a form fill-in box).

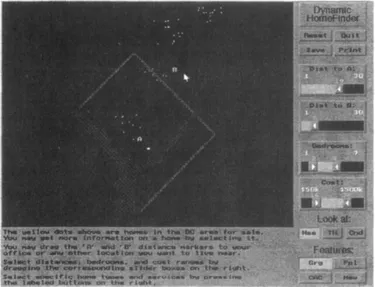

At about the same time, Christopher Williamson’s HomeFinder showed a map of Washington, D.C. and 1100 lights indicating homes for sale (Figure 1.1). Users could mark the workplace for both members of a couple and then adjust sliders to select circular areas of varying radii. Other sliders selected number of bedrooms and cost, with buttons for air conditioning, garage, and so on. Within seconds, users could see how many homes matched their query and adjust accordingly. Controlled experiments with benchmark tasks showed dramatic speedups in performance and high subjective satisfaction (93–01 [1.2], 94–16, 1993 video, 1994 video). This demo continues to be compelling and comprehensible even though it is more than ten years old.

Figure 1.1 The Dynamic Query HomeFinder showed 1100 homes for sale in the area of Washington, D.C. Users could set sliders to indicate distances from markers, number of bedrooms, and price.

Williamson earned a trip to the ACM SIGIR ‘92 conference in Copenhagen to present his work. Then he went on to the University of Colorado at Boulder to do a master’s thesis that expanded the idea into a well-engineered and commercially viable version. One of the amusing stories about this project was the unwillingness of corporate or university sources of regional housing information to share their data. Each organization felt protective of its data and saw little benefit to cooperating with us. Undaunted, Chris Williamson and his friends took a Sunday Washington Post and typed in the data for the 1100 homes. The resistance of these same institutions to learning about or applying our approach is surprising. They were successful with their current interfaces and satisfied with doing training courses so that staff could serve clients. They had little motivation to change to an interface that enabled users to do searches on their own, until a serious competitor arose.

Soon after, we worked with the National Center for Health Statistics and built prototypes of Dynamaps (93–21, 1993 video). A thematic map of the United States showing cancer rates was animated by adjusting sliders (Figure 1.2). A time slider illustrated time trends, and states or counties could b...