![]()

A Guided Tour through the Spider’s Web

After a minute of gorgeously composed shots of the barren, mist-swept Mount Fuji, reminiscent of suibokuga ink-painting, Kurosawa begins his human story with a subtle self-deprecating irony: he follows the opening credits – culminating in his own, which asks to be read down five levels of a column of Japanese characters – with a pan across some grave-marker slabs arrayed like another page of credits, then down a five-level sequence of Japanese characters resembling his own vertical listing a few seconds earlier. But this is the grave-marker of Spider’s Web Castle, and in saying so, it also declares itself a gravestone of this film whose name it bears, and announces the film as the gravestone of the world it reconstructs. Ars longa, but the medium fades. This column, its wood worn and the ink thinned with age, is the core of the monument marking the site of the long-erased castle through which the film’s characters materialised their transient claims to glory.

The opening chant echoes some standard Buddhist precepts about the transience of worldly aims and acquisitions; it will be essentially replicated in the song of the Forest Spirit, who corresponds to Macbeth’s witches, and then repeated to close the film. As reinforced by the image of open ground where the great castle once stood, the warning also corresponds to a haiku by Bashō – Japan’s greatest seventeenth-century poet (as Shakespeare was England’s), writing in a genre Kurosawa himself practised – apparently inspired by visiting an old battlefield: ‘Summer grass – /all that’s left/of warriors’ dreams.’ The English literary text that best summarises the ironies of this erasure may be, not Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias’:

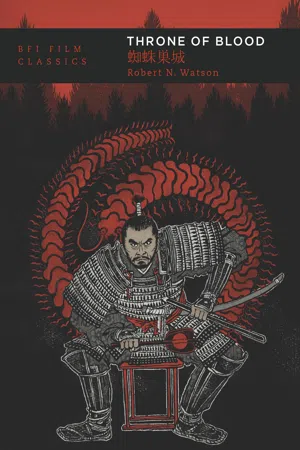

Opening credits for the lead actors, Toshirō Mifune and Isuzu Yamada; and the grave-slabs in the opening montage

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings.

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The film’s opening landscape is dark and barren, the weather is dull and bleak, there is no individual human voice, and all that survives is a weathered, abandoned obelisk surrounded by nameless graves. The Buddhist lessons of mujōkan (impermanence) and mu (nothingness) are conveyed by ku (the artistic deployment of empty space), as James Goodwin has explained.24 The flattening effect of the telephoto lens25 (pioneered in Japanese cinema by Kenji Mizoguchi and here employed by Asakazu Nakai) and the deadening of the treble in the sound palette augment the depressive force of this opening sequence. They correspond to Kurosawa’s rejection of the original tall design of the buildings: this is a world that constantly tamps down anything that seeks to lift itself out of the ordinary, any aspirations to individuality and ascendancy.

The vasts of space in Kurosawa’s befogged mountain setting for Throne of Blood serve to signal also the vasts of time. They establish a contrast that will be exploited to render more needful but also more futile the human struggles of the plot, and to emphasise the claustrophobia of the film’s low interior spaces, as part of an ongoing contrast between human aspirations (intense, but finally trivial) and the world in geological time (seemingly passive, but finally overwhelming, as ‘Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow/Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,/To the last syllable of recorded time’26). Where Shakespeare opens with the vivid Weird Sisters, suggesting the superior power of the supernatural over Macbeth, Kurosawa frames his story instead with the blank superior power of the natural, which has long since erased the glorious structure for which we are about to see people struggle so desperately. Clearly – that is, foggily – nature has its own dissolves, into which time disappears: by fading to the story as a distant flashback, the cinematic medium becomes (not for the last time) complicit with the natural world in signalling the folly of most human striving.

Day One

The film then turns to action – action as strenuous and urgent as the opening sequence was stagnant and demotivating. An anonymous rider churns uphill, as almost everybody seems obliged to do in this film, as if the world were an Escher stairway, as it seems also in the Sisyphean climbs that punctuate Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress a year later. The rider falls to the ground and pounds frantically on the bottom of the giant outer gate of a castle, with a low-angle shot reinforcing the sense of overwhelming obstacles; Kurosawa thus replaces the porter’s comic complaint about persistent knocking on Macbeth’s door with an emblem of human desperation. Mount Fuji, where Kurosawa chose to shoot these scenes, would have been an apt locale for recognising human civilisation similarly dwarfed by the power of nature.

His officers’ lack of any plan beyond miserably enduring a siege exasperates Great Lord Tsuzuki in this opening sequence, and will exasperate Great Lord Washizu in a similar tableau before the final battle. That Kurosawa intended the parallel is clear from the screenplay, which describes both sets of advisors as ‘gloomily silent’.27 Both instances suggest the discomforts – for those who have had a taste of glory in their prime – of accepting ordinary survival, playing out the string of a declining old age, where (as the supply-officer reports to the Great Lord here) one can only hope to ‘eke out three months, slurping gruel’.

The passivity and impassive expression of Tsuzuki (and his senescent, almost silent and motionless officers) echoes the emasculation of Shakespeare’s Duncan, who is repeatedly unable to defend himself. This failing is set against the heroic efforts of the messengers, and of the warriors they praise: Washizu and his friend Miki (the Banquo role, played by Minoru Chiaki), whom we then see on the backs of similarly striving horses. We see them, however, through the tangled – and implicitly entangling – undergrowth of the forest, which repeatedly comes into primary focus as a chastening reminder that the heroic story may not be the most fundamental one: growth, decay and erosion will wait out and wipe out human creations.

The film thus establishes early on not just its signature tension between the grid and the tangle, and not just its signature rhythm of eerie stillness alternating with violent agitation (matching Kurosawa’s belief that in Noh ‘quietness and vehemence co-exist together’28), but also the implication that this rhythm corresponds to the tension between the stasis of the collective world and the brief, desperate, erratic appetite of individuals. As Washizu and Miki ride through a weird mixture of rain and sunlight (matching Macbeth’s famous opening line, ‘So foul and fair a day I have not seen’), their determined masculine efforts, with spear and arrows, are therefore all the more refreshing and impressive. But those efforts are also scoffed at by circumambient nature: the conventional westernised brass accompaniment of a heroic charge that revs up as the men do (in contrast to the minimalist traditional Japanese instrumentation of most of Masaru Satō’s score) is erased by demonic laughter within twenty seconds. It is hard to imagine a more vivid depiction of the absurd battle between human will and natural entropy than these men’s effort to attack the weather and the forest with their weaponry. Washizu’s announcement that, against the ‘evil spirit’ trapping him in the forest, he ‘shall depend on my faithful bow and arrow’ recalls a Buddhist ritual of archers shooting at evil spirits,29 but also foreshadows the final scene when the arrows of soldiers who have lost faith in Washizu will trap and kill him: his prideful assertion will prove to be his punishment, matching the extensive pattern of poetic justice that pervades Macbeth.

In an echo of the thematic tension, this scene intersperses tracking shots that follow the riders with some stationary shots that emphasise the stability and stillness of the vegetation around them, even pulling the focus to make the dripping vines, rather than the riders passing by them obliviously, the subject of the shot. (This contrasts with the more alienated view of the forests Kurosawa offers in Dersu Uzala [1975], where ‘the camera pans only to follow figures’,30 although there too the point ultimately seems to be that forests swallow up human life indifferently.) We are spying on the riders from the position of nature, and that is finally as predatory as spying down from the arrow-slots on enemies approaching the invincible Spider’s Web Castle. The camera in the opening scene within the castle was as static as the characters: all symmetrically framed against a nearly blank battle-screen, and held in long shots. Our introduction to Washizu is instead dynamic and often close up, registering the passion of a soldier astride a live mount, rather than perched on traditional little stools like the lords in the previous scene. We are thus drawn visually, as Shakespeare draws us verbally, into the allure of the protagonist’s unsettling powers, even while receiving signals on another frequency warning that those powers are, in both senses, vain.

The two warriors, already visibly caught in the dark tangles of Spider’s Web Forest; Great Lord Tsuzuki and his generals passively receive bad news

Washizu and Miki then receive those dispiriting signals explicitly from the Forest Spirit, though it weaves delusive promises of glory into the warning. The bamboo stalks and branches tied with vines that comprise the Spirit’s thatched hut offer a middle case between the neatly manufactured planks of the other buildings and the wild growth of the forest – a contrast that will eventually return to prominence when the forest comes to recapture the fortress. At first the trunk of a massive tree hides the centre of the hut where the Spirit squats, but the dark, ancient tree m...