- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

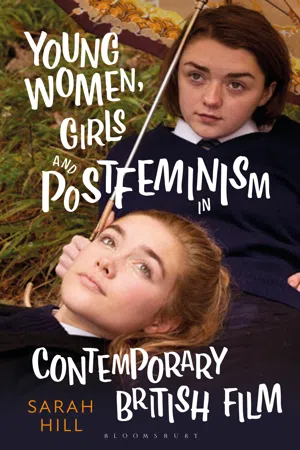

Young Women, Girls and Postfeminism in Contemporary British Film

About this book

In the 21st century, films about the lives and experiences of girls and young women have become increasingly visible. Yet, British cinema's engagement with contemporary girlhood has - unlike its Hollywood counterpart - been largely ignored until now. Sarah Hill's Young Women, Girls and Postfeminism in Contemporary British Film provides the first book-length study of how young femininity has been constructed, both in films like the St. Trinians franchise and by critically acclaimed directors like Andrea Arnold, Carol Morley and Lone Scherfig. Hill offers new ways to understand how postfeminism informs British cinema and how it is adapted to fit its specific geographical context. By interrogating UK cinema through this lens, Hill paints a diverse and distinctive portrait of modern femininity and consolidates the important academic links between film, feminist media and girlhood studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Young Women, Girls and Postfeminism in Contemporary British Film by Sarah Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Education and ‘sexualization’ in the British girls’ school film

In the introduction, I argued that British cinema has seen a significant increase in the number of girl films in the twenty-first century as part of a more concerted engagement with girl culture and an increased effort to attract youth audiences. One of the ways in which this is apparent is through the increase in girls’ school films during this period. These films, I argue, function in part to explore contemporary postfeminist anxieties about girls’ sexualities and ‘sexualization’ (Ringrose 2013). The school film has always been considered a quintessentially British genre. As Stephen Glynn argues, ‘the school film constitutes part of the DNA of British cinema and society’,1 its narrative allowing filmmakers to ‘comment on explicit education and broader socio-cultural issues’.2 Films such as Goodbye, Mr Chips (Wood 1939) presented the boarding school as a safe and unchanging world that ‘promoted the wisdom of the traditional value system’.3 British cinema’s interest in the school film intensified during the 1950s, along with an increased desire to attract youth audiences in the face of competition from television and other leisure activities.4 By the 1960s, the Labour government was making plans to introduce comprehensive secondary education that moved away from selection. By 1965, the boarding school film had virtually disappeared, with Lindsay Anderson’s If (1968) signalling a violent end to the boarding school film through post-war rebellion against public school order and tradition as the school is literally blown up.5 Historically, girls have largely been absent from the British school film genre, except for notable examples such as the St Trinian’s series (1954–66, 1980) and The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (Neame 1969), which centred around the charismatic Jean Brodie (Maggie Smith) and her select group of pupils at a school in the 1930s. There is a much richer tradition of British girls’ school stories in literature, however, through the work of Angela Brazil and Enid Blyton’s Mallory Towers series.

British cinema’s renewed interest in the school film was undoubtedly fuelled by the phenomenal international success of the Harry Potter film franchise, which offered not just magical fantasy but also a nostalgic fantasy version of the past and traditional notions of Britishness.6 The cultural influence of Harry Potter on perceptions of the British boarding school and the British school film is evident in the two contemporary-set school films discussed in this chapter – St Trinian’s (Parker and Thompson 2007) and Wild Child (Moore 2008) – as both ironically draw attention to its legacy. On arriving at Abbey Mount boarding school, Wild Child’s Poppy (Emma Roberts) remarks, ‘What is this place, Hogwarts?’, while the ramshackle St Trinian’s is disparagingly deemed ‘Hogwarts for pikeys’.7 The girls’ school film has been a key feature of this increased interest in the British school film, encompassing a variety of genres and intended audiences, including St Trinian’s, Wild Child and the horror film The Hole (Hamm 2001). A number of recent girls’ school films have also been set in the past, such as An Education (Scherfig 2009), Cracks (Scott 2008) – centred around a charismatic Jean Brodie-esque teacher Miss G (Eva Green) in a remote girls’ school in the 1930s – The Falling (Morley 2014) and (more ambiguously) Never Let Me Go (Romaneck 2010). In a number of these films, girls’ education takes place within the confined and highly regulated space of the single-sex school, where tensions, passions and jealousies destabilize the school’s order. This has historically been a key feature of the British girls’ school film and one to which it continues to return. The British school film also continues to be ‘most unyielding in its depiction of social class’, with an emphasis on upper-middle-class hegemony.8 The films analysed in this chapter – St Trinian’s, Wild Child, An Education and The Falling – all tend towards depictions of middle-class girlhood, or at least, not overtly working class. Even St Trinian’s, which has historically provided an antidote to this by featuring shabbier gentile girls or nouveau-riche girls, has moved towards depicting the characters as middle class in line with dominant discourses of postfeminist girlhood, which present white, middle-class femininity as the default ideal.9 Although still presenting a more ambiguous class status, the characters in the revived St Trinian’s were considered to have ‘gone posh’ in comparison with the girls from the original films of the 1950s and 1960s.10

This chapter explores how the same-sex school functions in British cinema as a representational site through which to explore contemporary anxieties about girls’ sexuality and sexualization. As Stephen Glynn notes, in the British school film ‘burgeoning female sexuality has been a constant source of quasi-terror and demonised as corrosive to a fully functioning society’.11 The contemporary British girls’ school film is therefore ideally placed to explore ‘postfeminist panics’ over girls’ sexuality and sexualization, which have emerged alongside girls’ increased visibility within educational discourses via the figure of the ‘top girl’.12 . As Angela McRobbie has argued, since the 1990s, young women have been cast as the key beneficiaries of social change and offered a notional form of equality in the guise of ‘the new sexual contract’. Education is a key site in which this new sexual contract is mobilized, where young women are encouraged to use their newly acquired ‘freedom’ to gain qualifications and earn enough money to enable them to participate in consumer culture.13 Here, girls, more so than boys, are marked by their grades and occupational identities, with a particular ‘luminosity’ on the ‘top girl’, a figure mobilized on the values of the new meritocracy promoted by New Labour that coincided with a period of expansion of higher education.14 The ‘top girls’ are hard-working, high achieving – usually white and middle class – and destined for Oxford or Cambridge.15 This increased focus on girls’ educational success has, somewhat inevitably, led to a backlash in the form of a moral panic about boys’ failure that is centred around white working-class boys in particular.16 This concern is exemplified by comments made by the Conservative minister for Universities and Science, David Willetts, in 2011, when he claimed that feminism was the ‘key factor’ contributing to the economic decline in the UK, as the increase in education and employment opportunities for women since the 1970s had led to a lack of social mobility for working-class men.17

The rise of the ‘top girl’ has occurred simultaneously with a moral panic over girls’ sexuality and ‘sexualization’, particularly the idea that girls are being ‘adultified’ and sexualized before they are ready. This panic reached fever pitch in the 2000s via a ‘consistent stream of newspaper headlines’,18 government reviews such as the ‘Review on the Sexualization of Young People’19 and campaigns such as Mumsnet’s ‘Let Girls be Girls’, which was concerned that ‘an increasingly sexualised culture was dripping toxically into the lives of children’.20 This concern over the sexualization of girls in particular exists alongside the rise of what journalist Ariel Levy has termed ‘raunch culture’, a strand of postfeminism that emerged in the early years of the twenty-first century, promoting a ‘pornified’ version of female sexuality that encourages women to make sex objects of themselves in order to feel empowered.21 Younger girls were also incorporated into this raunch culture through media imagery and consumer culture, such as clothing with ‘sexy’ slogans, which fuelled concern that girls were being encouraged to become sexually active at a (too) young age. As Jessica Ringrose argues, this concern over sexualization is a specifically postfeminist panic because sexualization is poisoned as a result of ‘too much and too early sexual liberation on the back of feminist gains’.22 Girls’ sexuality is therefore simultaneously presented as ‘at-risk’ from sexualization via media and consumer culture and ‘risky’ through their supposed participation in such a culture.

This chapter examines how young femininity is constructed within recent British girls’ school films via the mediation of the postfeminist ‘sexualization’ discourse, as well as educational discourses more broadly, beginning with two contemporary-set boarding school films: St Trinian’s and Wild Child. I analyse these films in relation to the ways in which they engage with contemporary discourses around girls’ education and sexuality, and also how they utilize the postfeminist makeover trope to construct a nationally specific postfeminist feminine identity as the ideal. St Trinian’s and Wild Child are two examples of British tween films. As Melanie Kennedy has theorized, the tween is a gendered, aged, raced and classed subject engaged in a transitional process of ‘becoming’ from girlhood to young womanhood. Emerging in the 1990s, the tween is a discursive construct of the postfeminist context, ‘marked by the distinct coming together of the rhetoric of choice and authenticity, together with the themes of makeover, princesshood and celebrity’.23 Tween popular culture grew exponentially during the 2000s, dominated by Disney, via texts such as the Hannah Montan a television series (2006–2011) and the High School Musical film franchise (2006, 2007, 2008). These texts construct and address the tween as needing to build and maintain an appropriate ‘authentic’ feminine identity through a rhetoric of choice that presents a postfeminist identity as the ideal and ‘natural’ choice.24 While, on the one hand, the tween (and tweenhood) is a discursive construct, on the other hand, it is also a consumer demographic consisting of girls aged between nine and fourteen years. St Trinian’s and Wild Child represent British cinema’s attempts to address this audience within an area of popular culture that has been dominated by the United States. In doing so, I argue, these films construct a British postfeminist identity as the ideal.

Following this, I discuss two girls’ school films set in the 1960s: An Education and The Falling. The 1960s setting is significant here because it marked another period when concerns and anxieties around young women’s sexuality came to the fore. This was the decade that witnessed key moments of political and social change, such as the introduction of the contraceptive pill in 1961, although initially only for married women, and the legalization of abortion in 1967. The idea of the ‘swinging sixties’ dominates cultural representations of the period, particularly via the figure of the ‘single girl’, a youthful, liberated and mobile figure as depicted in British cinema by Julie Christie in films such as Billy Liar (1963) and Darling (1965). The figure of the ‘single girl’ chimes closely with the ‘empowered’ young woman of postfeminist culture, so it is unsurprising that texts set in the 1960s function as a site of, what Lynn Spigel terms, ‘postfeminist nostalgia’. Using the US television series Mad Men (2007–2015) as an example, Spigel argues that this postfeminist nostalgia offers a reimagining of the past, where urbane and cosmopolitan women have a certain amount of power and mobility but do not yet have feminism.25 However, An Education and The Falling trouble this idea of postfeminist nostalgia via the confined space of the British girls’ school where the 1960s are yet to swing.

Postfeminist (school)girl power in St Trinian’s (2007) and Wild Child (2008)

In 2002, Ealing Studios announced that it was reviving the iconic St Trinian’s films as part of a £50 million redevelopment plan. Based on the cartoons of Ronald Searle, the St Trinian’s series began in 1954 with The Belles of St Trinian’s (Launder 1954). The original series consisted of five films produced between 1954 and 1980 and dealt with the exploits of the unruly pupils of the infamous St Trinian’s School for Young Ladies. As Emma Bell notes, the films ‘play[ed] on the postwar decline of the British upper class’ with its depiction of a crumbling relic of a boarding school, the elitist ‘cradle of the British class system’. More importantly, the films depicted young womanhood as unruly, offering the pleasure of the ‘spectacle of the destructive female group that challenged established social order’.26 The legacy of the films and their depictions of law-breaking schoolgirls who liked to drink, smoke and gamble mean that ‘St Trinian’s has become shorthand for anarchic female subordination’.27

The St Trinian’s films are associated with a ‘peculiarly British’ representation of girlhood,28 so it is unsurprising that this iconic girl-centred series should be revived during a period when British cinema showed a significant interest in girls and young women, and made a concerted effort to attract youth audiences. St Trinian’s (2007) was directed by Oliver Parker and Barnaby Thompson and produced by Ealing Studios with support from the UKFC, with a budget of £7 million. The film stars Rupert Everett as headmistress Camilla Fritton and Talulah Riley as new girl Annabelle Fritton, who arrives at St Trinian’s as an ex-pupil of the prestigious boarding school Cheltenham Ladies’ College. In order to revive the school’s finances and prevent its closure, the girls devise a heist to steal Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring from the National Gallery. The film was a surprise success, making around £12.5 million at the UK box office.29 Producer Barnaby Thompson attributes the film’s success in part to the fact that the film targeted girls aged between ten and sixteen, which he highlights as an underserved demographic within British cinema: ‘For them to see other girls up on screen leading the story was something they found thrilling that they could relate to.’30 With the redevelopment of Ealing, and its reputation hinging on St Trinian’s, it was hugely important that the revival was a success not only at home but also internationally. Ealing’s Head of Sales, Natalie Brenner, was fully aware of the challenges of selling a very ‘British’ film series that ‘has a history of being successful only in the UK’ to international audiences.31 It was therefore crucial that the film included a mix of this ‘peculiarly British’ representation of girlhood that St Trinian’s is known for, along with transatlantic ele...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Series Editors’ Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Girlhood and contemporary British cinema

- 1 Education and ‘sexualization’ in the British girls’ school film

- 2 The ambitious girl and the British sports film

- 3 Girl friendship and the formation of feminine identity

- 4 Young femininity and the British historical film

- Conclusion: Young femininity in contemporary British cinema

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Teleography

- Music

- Index

- Copyright