![]()

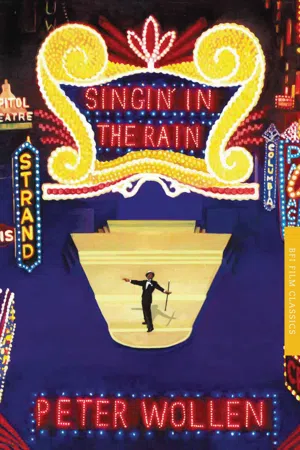

‘Singin’ in the Rain’

1

The history of cinema coincides with that of twentieth-century dance. In the first decade of our century, dance was revolutionised. Diaghilev and his choreographer, Fokine, changed the course of ballet, making it into a contemporary form which could survive the collapse of the ancien régime. Isadora Duncan set the agenda for the amazing expansion of ‘modern dance’. And, it should not be forgotten, Bert Williams and George Walker launched the cakewalk, took black vernacular dancing out of the circumscribed world of the minstrel show, and laid the foundations of modern tap and show dancing.

When historians look back on this astounding revolution in one of the most ancient of the arts, they will be dependent for their research on choreographic notation, which was developed during the same period, on verbal description by critics and dancers, and, most important of all, on photography, film and video – pre-eminently, on film. On one level, film has served as a recording medium for dance performance and as such has played a crucial role in preserving twentieth-century dance, although even then, tragically, an enormous amount has simply been lost. Very little of the work of the Ballets Russes is on film, for instance. But, on another level, as film itself developed as an art form, it intersected with dance to create a new phenomenon – film dance, dance created expressly for film, with camera, framing and editing in mind.

The single most memorable dance number on film is Gene Kelly’s solo dance ‘Singin’ in the Rain’, in the film of the same name, which he co-directed in 1951, with Stanley Donen, for the Freed Unit at MGM. Despite a bumpy opening, when the film was shunted aside after its premiere in April 1952 in order to make way for the re-release of MGM’s An American in Paris (1951), which swept the Oscars later the same month, it nonetheless turned out to be an enormous popular and box-office hit. In time, it also enjoyed an acknowledged critical success, eventually reaching the number four slot in Sight and Sound’s 1982 fiftieth anniversary poll of world critics’ ‘Ten Best Lists’, placed behind only Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941), Jean Renoir’s La Règle du jeu (1939), and Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954).

‘Singin’ in the Rain’ is an aesthetically complex production. Kelly was the performer, the choreographer and, with Donen, the director. Carol Haney assisted with the choreography. The music for the song was written by Nacio Herb Brown and arranged for the film by Roger Edens. The lyrics were by Arthur Freed (also the producer), adapted by Kelly, who added ‘and dancin’’ to the title line. The cinematographer was Harold Rosson, who had worked with Kelly and Donen before, filming On the Town for them in 1949. They had specifically requested that Rosson replace John Alton, who had originally been assigned to the picture, following his success with An American in Paris, which starred Kelly but was directed by Vincente Minnelli, whose style was very different. Finally, of course, many other people were involved in countless other ways.

It is worth looking a bit more closely at what actually happened on and off the set to produce the sequence. First, Kelly knew that somewhere in the film, as the star, he should have a featured solo dance. The script, by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, had been written over a year before, while Kelly was busy working on An American in Paris; and, although it was written with him in mind, it did not specify any particular number for his solo. In fact, ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ is placed in the same position in their script, after the disastrous preview of The Duelling Cavalier, but they envisaged it as a number for the trio of Don Lockwood (Kelly), Cosmo Brown and Kathy Selden, who at that time were still uncast. The scene would begin, not outside Kathy’s house as in the finished film, but in a restaurant, and the trio would dance off their stools out into the street and the rain, in an atmosphere of ‘impromptu fun’. This idea was basically a reprise of the ‘Make Way for Tomorrow’ number which Kelly, Rita Hayworth and Phil Silvers had danced in Cover Girl (1944). Here too the three of them dance out of a restaurant and along the street, up and down the stoops, ducking into doorways to avoid a disapproving policeman, having fun with props on the way.

Although Kelly decided to make ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ his solo, the trio was retained as the credit sequence for the film, a number now partly based on its very first film appearance in Hollywood Review of 1929. But Kelly does still retain some key elements of ‘Make Way for Tomorrow’: not only the dancing down the street, but also details such as the suspicious cop. The main concept of the dance, however, now comes from the lyrics of the song. As he himself put it, ‘It’s got to be raining and I’m going to be singing. I’m going to have a glorious feeling, and I’m going to be happy again’.1 This illustrative approach to dance is not as obvious as it sounds. It depended on the song being placed at a point in the story where glorious feelings were appropriate, and thus on the integration of the dance number into the narrative.

Gene Kelly, Rita Hayworth and Phil Silvers in Cover Girl

The credit sequence of Singin’ in the Rain

On one level, Singin’ in the Rain can be seen as a backstage musical, whose story basically boils down to ‘putting on a show’, as in the cycle of Judy Garland–Mickey Rooney musicals Busby Berkeley made for the Freed Unit in its earlier years. Now, instead of amateur theatricals in the barn, the show is the first musical picture being made at Monumental, a fictional Hollywood studio. However, unlike the conventional ‘putting on a show’ musical, in Singin’ in the Rain the musical numbers are not limited to the film within the film but also occur at regular intervals within the framing story, built round the relationships between the major characters. They are stitched into the dramatic action. The ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ sequence is not just an entertainment interlude, it is conceived as an expression of Don Lockwood’s feelings at a particular point in both his professional and his personal life.

This preoccupation with the ‘dramatic integrity’ of the dance numbers derives, to an important extent, from developments in the Broadway stage musical. In the early 1940s the operetta and the musical comedy developed a new vision, whereby dances were integrated into the drama as expressions of characters’ moods and feelings, rather than slotted in simply as opportunities for spectacular dancing. This development coincided with the shift of responsibility for dances from a ‘dance director’, responsible for spectacle, to a ‘choreographer’, responsible for dramatic dance. In the end, the choreographer, instead of being a subordinate, began to be the major figure in the production of a musical, and Kelly’s own example, in the cinema, contributed significantly to this trend. On Broadway, the decisive step is usually attributed to Agnes De Mille, for her work as choreographer of Oklahoma! in 1943.

In fact, this change within the Broadway musical reflected a change in American ballet: the inauguration of a specifically American style of choreography, dealing with American subjects and dramatising the dancing. In the spring of 1938, Lincoln Kirstein’s American Ballet Caravan had put on an All-American Evening in New York, featuring Show Piece with music by Robert McBride and choreography by Martha Graham’s star dancer, Erick Hawkins; Yankee Clipper, with music by Paul Bowles and choreography by Eugene Loring; and Filling Station, with music by Virgil Thomson and choreography by Lew Christensen. In all three of these ballets the choreographers were also the dancers. They were soon followed up by two ballets with music by Aaron Copland, Loring’s Billy the Kid, in October 1938, and De Mille’s Rodeo in October 1942, which led directly to Oklahoma!, followed by Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free in April 1944, which was then transformed into the stage musical On the Town by Comden and Green later the same year.

This period in American dance history was also the period in which Gene Kelly left his native Pittsburgh, arriving to work in New York in August 1938, before moving on to Hollywood in November 1941 and directing his first film, On the Town, too many years later, in 1950. As soon as he arrived at the Freed Unit, Kelly began agitating to get new choreographers out to Hollywood from New York, as well as experimenting with the new choreography in his own numbers. Particularly, he was interested in Eugene Loring, who was brought out to the Freed Unit in 1943 and went on to work on Minnelli’s Yolanda and the Thief (1945); and, much later, as choreographer of Funny Face (1956) and Silk Stockings (1957).

Kelly, however, came originally out of tap rather than ballet. In Pittsburgh his father had been a phonograph record salesman who, ironically enough in the light of Singin’ in the Rain, was put out of work by the slow-down of the record industry which followed the Crash, the rise of radio and the arrival of sound film. The Kelly family took up a new career, running a popular dance school in the Pennsylvania steel town of Johnstown. Kelly’s early experiences of performance were of tap dancing with his brother Fred and his sister Louise, who eventually dropped out, leaving Gene and Fred as a brothers act. It is interesting that, unlike Astaire, Kelly never danced with a regular female partner, and generally seemed to prefer male partners. Astaire, of course, began dancing with his sister Adele, whereas Kelly worked his way up with his brother Fred. They began in working men’s clubs, Moose Clubs, American Legion halls and so on, before graduating to vaudeville and ‘presentations’ (dancing with on-stage bands) and finally putting on their own shows. But, while still based in Pittsburgh, Kelly took a series of summer ballet classes in Chicago, studying with Kotchetovsky, who had been the partner and husband of Nijinska. In dance terms he was, so to speak, determined to be upwardly mobile, adding a ballet carriage and arm movements above the waist to tapping feet below.

Kelly’s experience in New York strengthened the inclination to dramatise his dance. His first important role was as Harry the Hoofer in Saroyan’s play The Time of Your Life, which opened in October 1939. This was Saroyan’s follow-up to The Great American Goof, the ‘ballet-play’ choreographed by Eugene Loring, who also danced the lead. Harry was one of a motley crew of bums, sailors, prostitutes and drifters frequenting a waterfront bar. Kelly commented later:

I realised that there was no character – whether a sailor or a truck driver or a gangster – that couldn’t be interpreted through dancing, if one found the correct choreographic language. What you can’t have is a truck driver coming on stage and doing an entrechat. Because that would be incongruous – like a lady opening her mouth and singing bass. But there was a way of getting that truck driver to dance that would not be incongruous just as there was a way of making Harry the Hoofer, a saloon bum, look convincing. It may seem obvious now, but at the time it was an important discovery for me.2

Saroyan saw Kelly as like a Chorus in the play, the rattle of whose taps ‘was not unlike a drum roll at a funeral’, while at the same time Harry was trying to cheer up the other barflies with his hoofing.

His success as Harry the Hoofer, the part of a dancer in a straight play, got Kelly the role which first made him a star, as Joey in the Rodgers and Hart musical Pal Joey, which opened the following autumn. Here too he was playing a hoofer, this time a heel living off his appeal to women and exploiting them and anyone else for whatever he can get. It was unusual for a musical in its pessimism and dark view of its central character, but again it gave Kelly an opportunity to develop a dramatic role through his dancing. John Martin, the critic of the New York Times, wrote that ‘the whole production is so unified that the dance routines are virtually inseparable from the dramatic action’. Robert Alton, the dance director for the production, was Kelly’s principal sponsor in the city. He had spotted Kelly in Pittsburgh and it was because of his invitation that Kelly had come to New York. In due course Alton too came out to the Freed Unit, where he became the most employed dance director, working with Kelly again on The Pirate (1948) and Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949). Alton’s ambitions pointed the way towards the integration of choreographer with stage or film director. In 1934 he had already developed a desire to ‘pick up pointers in straight direction with the goal of ultimately directing the book and the dances of a musical comedy.’3 He was the major influence on Kelly’s career, in the sense that he both discovered Kelly and crystallised the nature of his ambition.

Tap dancing had always had a dimension of ‘character dancing’, but this was mainly for purposes of comedy. Kelly moved character dancing into the dramatic mainstream. At the same time, in tension with the drive towards integration, he stayed loyal to his roots in tap. Tap dancing differs from most other forms of dancing in that it appeals to the ear as well as the eye. In fact it is defined by the rhythmic sound of the metal taps on heel and toe, which distinguish it from its neighbours, clog and softshoe dancing. During the 1930s, tap dancers, such as the Nicholas Brothers or Fr...