eBook - ePub

Greed

About this book

Greed is a legendary film begun in 1923. It was to have been Erich von Stroheim's masterwork, but his colossal ambitions were to be his undoing. His obsession with realistic detail and determination to extract every ounce of drama from his source, Frank Norris's novel McTeague, stretched the shooting schedule to inordinate lengths, resulting in a film which ran for over seven hours. Jonathan Rosenbaum has made a meticulous study of all the sources. In a fascinating piece of detective work, he reconstructs the history of one of cinema's greatest ruins.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

ASPECTS OF PRODUCTION: THE NORRIS TEXT

If Stroheim's career has generally been treated as a series of acts more than of works, there is little doubt that Frank Norris encouraged and elicited a similar treatment. Both men looked upon the American working-class milieu which they depicted, from a certain voyeuristic distance, and both projected a romantic self-image of sophisticated world traveller and adventurer, valuing their 'honesty' - a form of aesthetic scruple to be waged against genteel idealism - above all else.

Yet precisely because McTeague and Greed have been identified so often with Realism (a label denied by Norris, who described himself as a Naturalist), it is worth noting at the outset the peculiar relationship that Norris had with his own material. Unlike Stroheim, he never had any direct experience of poverty. On the contrary, the marked class difference between the characters of McTeague and Norris himself- a dilettante in Paris and loyal fraternity brother at Berkeley who wrote most of McTeague for a 'creative writing' course at Harvard; a Zola enthusiast whose father died a millionaire and whose mother helped to finance the publication of his first book (a feudal romance in verse inspired by Sir Walter Scott) - was undoubtedly part of his incentive for writing the novel. The lure of exoticism, which led him to travel to South Africa (1895) and Cuba (1898) in search of adventures to write about, also carried him the few blocks in San Francisco from his family's house in a nouveau riche neighbourhood on Sacramento Street to the poorer section on Polk Street where his mother did her shopping.4

In striking anticipation of the procedures of future film-makers, Norris scouted locations for the novel he would eventually write: the upstairs office on the corner of Polk and California that McTeague's Dental Parlors would occupy, the nearby lunch counters and saloons, Scheutzen Park in Oakland, and other sites. The Lester Norris Memorial Kindergarten - financed by his family, with his mother on the board - served as the last working address of Trina, where she is murdered by McTeague during the Christmas season; while visits to a fraternity brother at the Big Dipper Mine supplied Norris with settings that occur near the end of the novel.

Like many later film-makers, Norris's relationship to his seedy milieu was basically that of a tourist, suggesting a fixed distance that is only set in relief by the veiled personal references and in-jokes inserted into the narrative. Trina's dental appointments with McTeague coincided with the meetings of Norris's creative writing course at Harvard (the novel itself is dedicated to the teacher of that course, L. E. Gates); Norris's mother figured obliquely as one of the 'grand ladies of the kindergarten board' who put up Christmas decorations; and Norris himself made a brief Hitchcockian appearance - 'a tall, lean young man with a thick head of hair surprisingly gray, who was playing with a half-grown Great Dane puppy' - at the Big Dipper Mine towards the novel's end. Norris may have been, by his own account, a writer who believed that 'life is better than literature', but there is little question that his understanding of 'life' was formed to some extent by his experience of literature.

Clearly, the unremitting physicality of Norris's prose in McTeague makes it an anticipation of cinema in much the same way that, according to Eisenstein, Dickens inspired the film forms of Griffith. But it's worth adding that the novel includes an early account of cinema which bears quoting in full, as it appears to impinge directly on the author's ironic notions about the artifice and audience of his own art:

The kinetoscope fairly took their breaths away.

'What will they do next?' observed Trina, in amazement.

'Ain't that wonderful, Mac?'

McTeague was awe-struck.

'Look at that horse move his head,' he cried excitedly, quite carried away. 'Look at that cable car coming - and the man going across the street. See, here comes a truck. Well, I never in all my life! What would Marcus say to this?'

'It's all a drick!' exclaimed Mrs Sieppe, with sudden conviction. 'I ain't no fool; dot's nothun but a drick.'

'Well, of course, mamma,' exclaimed Trina; 'it's —'

But Mrs Sieppe put her head in the air.

'I'm too old to be fooled,' she persisted. 'It's a drick.'

Nothing more could be got out of her than this.5

One should note that Norris wrote the first nineteen chapters of McTeague between 1893 and 1895 while attending the University of California at Berkeley and Harvard. (One of his initial inspirations was the newspaper coverage of the violent murder in San Francisco of a kindergarten janitress by her estranged and alcoholic husband in October 1893, when Norris was a senior at Berkeley.) He wrote the last three chapters in 1897, after travels abroad to South Africa and Britain and a visit to the Big Dipper Mine to see his friend and fraternity brother Seymour Waterhouse, who worked there as a superintendent - a place he would return to sixteen months later to finish the novel.

This two-year hiatus in the writing of McTeague has some significance in so far as it marks a certain shift in the novel's overall literary conception. Undecided about how to conclude his story after the murder of Trina - a murder whose real-life counterpart apparently served as the novel's principal inspiration - Norris eventually arrived at a solution that sharply changes the literary cast of the novel from Naturalism to Allegory, with a radical shift of space from San Francisco to Death Valley. This suggests the hypothesis that Norris's choice of milieu - in his terms, a choice of 'life' over 'literature' - negated the possibility of a literary resolution to his plot. To arrive at this, he needed a location that was less socially determined and more abstract and symbolic, where literary associations were more readily available.

2

ASPECTS OF PRODUCTION: THE STROHEIM TEXT

Born on 22 September 1885 in Vienna, Erich Oswald Stroheim (his original name) was the son of Benno Stroheim, a dealer in felt, straw and feathers from Prussian Silesia who later became a hat manufacturer, and Johanna Bondy, who came from Prague; both were practising Jews and Erich had a younger brother, Bruno, born four years later. Very little is known about Erich's early years - in large part because of the mythology he spread later about his links to the Austrian aristocracy and his military experience - although Richard Koszarski reports that one of his cousins, Emil Feldmar, told biographer Denis Marion that as a private soldier 'he deserted before the end of his regulation year and . . . emigrated to America' in 1909 'as a result of some mysterious indiscretion.'6

Identifying himself upon his arrival as a Hungarian clerk, he worked in diverse menial jobs, served as a private in the New York National Guard, and moved to San Francisco around 1912, where he met and married his first wife and wrote a play. After money problems, drink and physical abuse led to a divorce in 1914, he worked for a summer at Lake Tahoe, where he persuaded a wealthy married woman to produce his play in Los Angeles. It was a resounding flop.

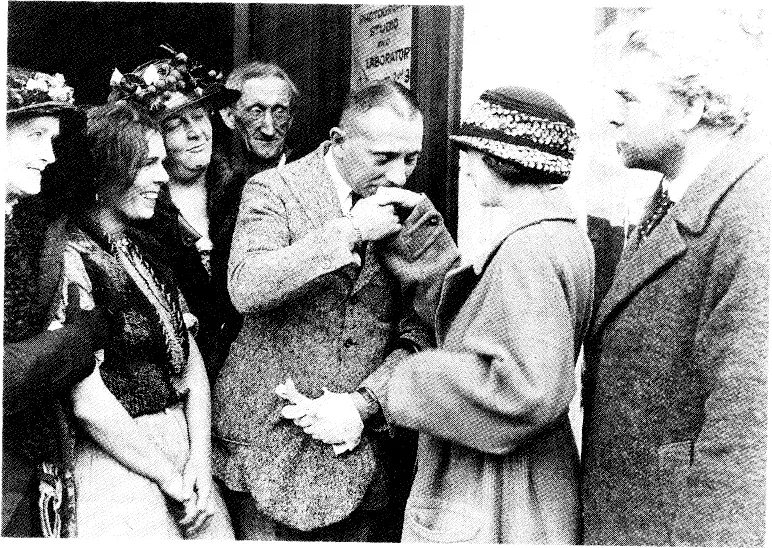

ZaSu Pitts and Gibson Gowland greeted by von Stroheim upon arrival in San Francisco

Stroheim entered film in 1914 as an extra on The Birth of a Nation, and by the next year was acting in various pictures, including several directed by John Emerson, as well as working as military adviser. By 1918 he was playing a secondary villain in Griffith's Hearts of the World and the star villain in The Heart of Humanity. (A second, unhappy marriage during this period yielded a son, as did his third and final marriage in 1919.) Walking for miles every day to sit outside Carl Laemmle's office at Universal, he eventually persuaded the studio head to back his first feature, released as Blind Husbands (1919). The critical and commercial success of that film and of The Devil's Pass Key the following year led to Stroheim's first blockbuster, the million-dollar Foolish Wives (1922), and Merry-Go-Round (1923). On the latter film, Stroheim was charged with 'insubordination' and 'disloyalty', fired by Irving Thalberg, and replaced by Rupert Julian about half a year before the start of production on Greed.

It remains a matter of conjecture precisely when Stroheim first came across a copy of Norris's novel. Georges Sadoul reports that Stroheim first encountered McTeague around 1914, in a boarding house in Los Angeles, while working as an extra; more recently, Koszarski has written that Stroheim claimed to have first discovered the novel 'during his down-and-out days in New York', 7 which would have been at some point between late 1909 and 1912.

Whenever the discovery was made, it apparently wasn't until 1920 that Stroheim first announced the novel as a film project. 8 In the interim, an earlier, five-reel film based on the novel - Life's Whirlpool, directed by Barry O'Neil, and starring Holbrook Brinn and Fania Marinof - was released early in 1916. According to Koszarski, 'Reviewers of the time were disgusted by the "repelling realism" of the film and its "revolting coarseness". Complaints about McTeague biting his wife's bleeding fingers were matched only by those denouncing the profusion of close-ups.'9 Apparently the parallels with Greed run even further: according to Kevin Brownlow, the final sequences were shot in Death Valley.10 Koszarski informs us that Stroheim criticised Blinn's performance in an interview while he was filming Greed in San Francisco, so there seems little doubt that he was familiar with Life's Whirlpool. Existing stills of this lost film also suggest that it may well have exerted some influence on Stroheim's own conception, although Idwal Jones, who reported seeing a nine-hour version of Greed at MGM on 12 January 1924, mentioned that both he and Jack Jungmeyer, 'the only other newspaperman there', recalled the earlier film adaptation in relation to Stroheim's as 'a lurid thing, rather comical now'.

Despite these apparent similarities, one cannot find many precedents for Stroheim's script for Greed or his production methods. While it was certainly true that other lengthy films had been made, and many others had already been shot largely or exclusively on location, the combination of these factors with the support of a large studio, a large budget and the obsessiveness of Stroheim's working methods made the project unusually daring and experimental, and one that was described as such in the current press.

One of the enduring mysteries about the project remains the fact that Goldwyn Company executives Frank Godsol and Abe Lehr actually approved Stroheim's 'final' script, drafted in San Francisco between January and March 1923, and virtually doubled the original budget (from SI75,000 to $347,000) before shooting began. According to Koszarski, both men 'had little aptitude for filmmaking', and despite Stroheim's reputation for massive expenditures they were apparently swayed by the force of his enthusiasm. Stroheim's 26-page contract, while generous, was less advantageous than the one he signed with Universal in 1920, holding him personally responsible for 'excess costs', so Godsol and Lehr may have figured that these and other 'negative inducements' would exert some influence over the proceedings.

As we have already seen in the case of Norris, whose desire for a dramatic climax with 'maximum' (therefore 'literary') resonance led him to shift his plot from a naturalistic to an allegorical space, Stroheim's own taste for pushing his conceptions to their limits often led to similarly contradictory and paradoxical results. On the surface, one could interpret his aim in using painstakingly authentic locations, costumes and props, and forcing his actors t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Aspects of Production: The Norris Text

- 2 Aspects of Production: The Stroheim Text

- 3 Aspects of Production: MGM

- 4 Aspects of Reception and Consumption: The Legacy of Greed

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Greed by Jonathan Rosenbaum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.