![]()

1 From No One to Someone

GA/FF/DA. The great conceit to which 8½ is considered to owe its place in cinema history only starts with the fact that the hero is a film director. Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), the hero in question (hereafter GA), is at once much more than a director, and much less. On the one hand, he is an auteur, a director who is also the artistic originator of his films, and enjoys international celebrity as such. On the other hand, floundering in full-blown midlife crisis, he shirks even the basic tasks of his métier to the point where he hardly knows what film he is supposed to be making. No longer the master he had shown himself in previous works, he has suddenly, inexplicably become embarrassed by the demands of authorship and reluctant to assume anything about it – except, that is, its central position, which is the one thing that he seems not to run away from. Only at the end of 8½, literally at the last minute, does he discover his subject, which proves to be none other than this struggle to find it. ‘All this confusion is me, myself.’ The insight allows him to resume his megaphone and, while Federico Fellini’s film is ending, GA’s finally begins.

As even this bald summary suggests, GA cannot simply represent ‘a’ director (such as we might find, less centrally positioned, in Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful [1952]); he incarnates ‘the’ director, the one responsible for the film we are watching. This film insinuates a mirror-construction in which we’re to understand GA as an image of FF, and GA’s story as a reflection of – and on – the coming-to-be of 8½ itself.2 Originally entitled ‘La bella confusione’ (‘A Fine Confusion’), 8½ repeatedly breaches the normally airtight levels of author and character, story-telling and story told. More than once, GA astonishes us by whistling a tune we have just heard on the soundtrack or by appearing in a shot that began as his own point of view. Such Escher effects only make sense under the assumption that GA’s project and FF’s achievement, if never identical, are always concomitant; at every moment, each is critically present to the other, and neither can be understood outside this ‘confusing’ mutual cross-referencing.

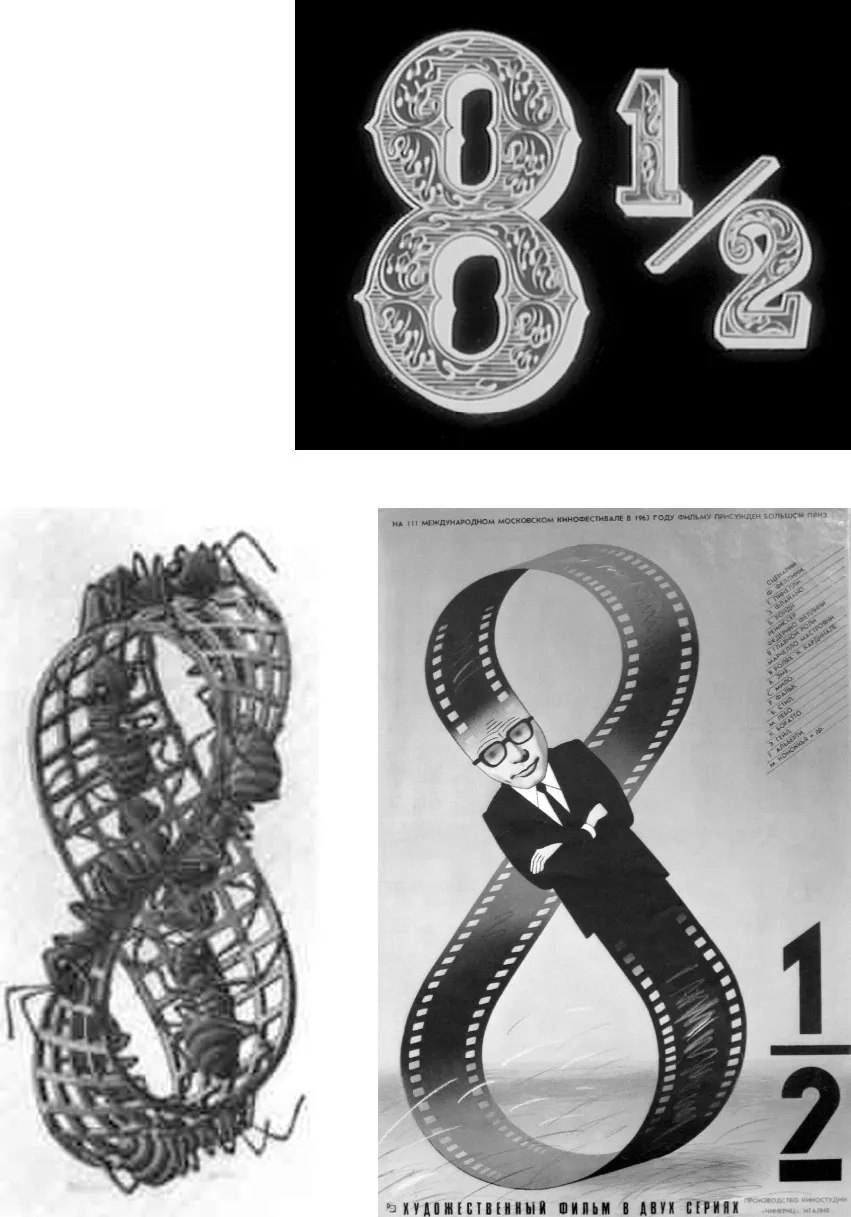

The insignia of this concomitance is the title itself, 8½. The single line of an ‘8’, of course, already contains two circles. But the film’s famous logo – the first image we see on screen – takes the doubling further: the black ovals inside these circles have been pinched so that each half of the ‘8’ silhouettes a miniature of the whole. The figure suggests, too, the Möbius strip, whose confounding continuity of inside and outside is conventionally represented as a three-dimensionalised ‘8’ – see Escher’s drawings or, even more to the point, the inspired poster for 8½’s first release in the Soviet Union. As for the fraction, it literalises the ambiguity between one and two inherent in the ‘8’ – and in the process renders the title a number midway between two integers, two ‘whole’ units. ‘8½’ thus heralds the monstrous hybrid, existential and conceptual, that no analysis of the film can avoid: GA/FF.3

No analyst can avoid it either. It is impossible to watch this film without entering the mirror-maze and being refashioned therein as a reflection of the hero/author. The objection made to 8½ at the time of its release – that the hero’s problems couldn’t possibly interest any viewer who wasn’t a film director – never made sense except as a defence mechanism against the fact that the film seduces every viewer into the fantasy of authorship, of doubling GA/FF both psychically and creatively. I am not sure that, as a critic, one can resist this grandiosity; the put-upon tone of those who try only confirms how far they have fallen victim to an imposition. I prefer to accept the absurd identification, to take myself – howsoever I can – for ‘the very person’ meant to be writing about 8½.

AUTHOR! AUTHOR! In the auteurist atmosphere that suffused European cinema in the late 1950s, Fellini’s invention was waiting to be discovered. The intellectual premise of auteurism was disarmingly simple: a work of art demanded an artist, and in the case of film, this could only be the film director, who controlled its structure and meaning much like the ‘author’ of a novel or poem. But its effect was to launch an unprecedented promotion of the director in film culture, to such an extent that his charismatic name – Bergman! Antonioni! Godard! – became as crucial to selling the art film as the glamorous image of the star continued to be in Hollywood advertising. Within a couple of years after Cahiers du cinéma espoused ‘the politics of the auteur’, the auteur throned over film journals, film festivals and art house marquees alike, until he virtually became a synonym for the art film itself, now conceived as a cinéma d’auteurs. (8½ came out at a high-water mark in this cinema’s expansion: in New York City, a key outpost of its empire, the film did not simply open at an art house; it opened, as the inaugural attraction, the house itself. This was the Festival Theatre, built and operated by Joseph E. Levine, then Fellini’s US distributor; its prime location, just off Fifth Avenue at 6 West 57th Street, has since been converted to retail.)

Like any other imperialism, that of the auteur implied a logic of ‘the next step’. On such a horizon, Fellini’s conceit was eminently thinkable. If (as auteurist critics liked to insist) the auteur was the real subject of his films, then why shouldn’t he become the ostensible subject as well? With everyone in the audience clamouring ‘Author! Author!’, why not acknowledge, why not oblige the demand by stepping out from behind the curtains? And not briefly, à la Hitchcock, or in a subordinate role, à la Godard in Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963), but in the full strength of his centrality? With 8½, the auteur, whom cinephile culture had been featuring everywhere but in the feature, now made a spectacle of himself. The effect was galvanising; to many intellectuals, it seemed as if, with this self-reflection, cinema had finally realised its theoretical ‘concept’. Directors in particular saw in 8½ the emancipation proclamation of ‘personal’ film-making, and could hardly wait to celebrate their freedom by producing, one after another, slavish imitations of Fellini’s film.

ZÉRO DE CONDUITE. But it is not simply the impetus of a triumphant auteurism that speaks in 8½’s governing conceit. As Fellini well knew, this conceit could only be undertaken as a piece of deliberate rule-breaking. Crucial to the auteur’s divinity had been an obliquity, even an abstraction of his person, that auteurist critics took good care to reinforce. They were looking for the (thematic, stylistic) consistency of a director’s signature, not for the details of his life or the specifics of his social condition. Though André Bazin famously complained that the ‘politics of the auteur’ risked becoming ‘an aesthetic cult of personality’, this cult was no more interested in the actual biography of Renoir or Rossellini than its political counterpart was willing to tell the masses everything that they were afraid to ask about Stalin or Mao. Hitchcock’s cameos are exceptions meant to prove this rule of good authorship. In a landscape populated by stars, the heavy, homely Hitchcock comes on screen only to establish his unsuitability to a fiction where his person is laughable, even a bit monstrous. For that reason, the incarnation is swiftly aborted; and the man who is too much disappears into the auteur who is everything.

Obviously, many an auteur had put himself into his work before 8½, but two precautions had always kept the autobiographical subtext from becoming the bad form that 8½ – where Fellini cast the part of GA’s mistress with his own – was widely felt to display. One was structural: the difference in narrative status that separates author and character and that requires any intimacy between them to take place indirectly, across great ontological barriers. This difference is particularly pronounced in film, whose grammar (certain marginal experiments aside) lacks the first person; even when a voiceover says ‘I’, the camera inclines to show us a ‘he’ or a ‘she’. The other precaution was rhetorical: a certain mist of tact, of understatement, enveloped the autobiographical aspect of a film so that it never interfered with – it could only enhance – a universal understanding of the story. The personal merely went to show that there was nothing very personal about it, nothing, at any rate, that couldn’t be absorbed into a person’s general social representativeness.

In this respect, Visconti’s Il gattopardo (The Leopard) and Godard’s Le Mépris, each of which came out in the same year as 8½, are both better-behaved auteurist productions. In Il gattopardo, the film’s aristocratic director, Count Don Luchino, no doubt draws some part of his likeness in the film’s aristocratic hero, Prince Don Fabrizio, but given the film’s mid-nineteenth-century setting, there can be no resemblance in point of film-making. Conversely, in Le Mépris, Godard employs the metacinematic device of the film-within-a-film, but he sets this self-reflection at an off angle to his central story. And it is difficult to think of the fictive director, called ‘Fritz Lang’, as an authorial surrogate for Godard, since the former is played by Fritz Lang himself, with the latter in the role of his assistant. If the biographical Godard is at all referenced in this distancing structure, it is only as a rat de cinémathèque, a lowly life-form over whom, from his place in the auteurist pantheon, Lang towers like a god.

In breaking auteurism’s cardinal rule of personal discretion, Fellini’s conceit was felt to be just that: the arrogance of a deplorable first flowering in the culture of narcissism. The vehemence with which his so-called self-indulgence was denounced can hardly be overstated, with many critics believing themselves under civic obligation to flaunt their disgust. ‘It wallows in self-abuse,’ wrote Joseph Bennett of the film, linking it to public masturbation and rolling in shit. Pauline Kael, in her review, compared Fellini first to a vain bisexual actor and then, lest the innuendo be thought obscure, to an hysterical couturier. All this, and more, in the name of good manners.4

THESIS. In 1963, then, there were two kinds of people in the world regarding Fellini’s fictional incarnation. For the enthusiasts, the trope of author-as-person had realised the manifest destiny of auteurism to take pride of place in front of the camera as well as behind it; it pioneered a species of film-making that was intellectually reflexive and personally intimate at once. For the detractors, the same trope had allowed Fellini to follow, all too precipitously, the course of least artistic resistance; for what could be easier, or more facile, than self-indulgence? But both parties agreed on what they were seeing: an affirmation of author and person alike, each enhancing the other’s value. Whether you cheered or contested the affirmation, you didn’t doubt that it was one.

That was how 8½ looked, not only in 1963, but also all through its youth.

Now, in the film’s middle age – or so it seems to me – the evidence is increasingly visible that Fellini’s ground-breaking conceit is not the confident or crass self-manifestation we once supposed. Now, on the contrary, it is apparent that the conceit is being constantly pulled back by a massive unwillingness to go through with it. Though he spearheads auteurist expansion, this auteur is also prey to strange fits of compunction when it comes to actually occupying the newly conquered territory; and again and again his cocky exhibitionism proves sapped by a meek and reclusive shame. In short, the trope of author-as-person betrays a mutual insufficiency, a common unsureness, in author and person. Let me call this conflict in the film – between affirming and retracting its ruling conceit – the author-person’s reluctance (from Latin reluctari, to struggle or resist). The reasons for it lie at the core of what 8½ is still asking us to understand.

TRAFFIC JAM. Fellini’s decision to make GA a director like himself was made in panic and desperation. Even in reminiscence, he almost courts Kael’s imputation of hysteria:

For two months, I worked on the script with Flaiano and Pinelli, but it wasn’t convincing because I couldn’t decide on what the protagonist did for a living. … I felt myself floundering; I was on the brink of abandoning the project. But I gave the order to start, that we beg...