![]()

ON THE WATERFRONT

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In 1955 On the Waterfront became one of the most honoured films at any Oscar ceremony. But unlike such spectacles as An American in Paris (1951), The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), Around the World in Eighty Days (1956) and Ben-Hur (1959), which also received Oscars, On the Waterfront was a work of gritty realism, more indebted to the look of Italian neo-realist films like Rome Open City (1945) and Bicycle Thieves (1947) than to the widescreen Technicolor extravaganzas of the studios. Produced by the maverick Sam Spiegel on a comparative shoestring, the film was at first what Elia Kazan, the director, and Budd Schulberg, the scriptwriter, called an ‘orphan’, turned down by every major studio, then grudgingly financed, shot on location along the Hoboken, New Jersey, docks across the Hudson river from New York City, and taking for its story working-class problems in a working-class neighbourhood.

Nevertheless, On the Waterfront received nine awards including Best Film, equalling the record of From Here to Eternity the previous year and Gone With the Wind nineteen years before. In addition, Kazan received the Oscar for Best Director (his second), while acting awards went to Marlon Brando and Eva Marie Saint, Best Story and Screenplay to Schulberg, Best Editing (Gene Milford), Best Black-and-White Cinematography (Boris Kaufman) and Best Black-and-White Set Decoration (Richard Day). Its Academy-Award-nominated music was written by Leonard Bernstein, his only original movie score.

On the Waterfront has endured as both a popular film and a classic while many of the more grandiose films of the period have disappeared from cultural memory. The incessantly repeated images of its taxicab confrontation between Brando and Rod Steiger have made the film iconic to huge audiences that may have never seen it in its entirety. With that scene, as well as the getting-to-know-you interchange between Brando and Saint over her glove, and the nominations of Karl Malden, Lee J. Cobb and Steiger for acting Oscars as well, On the Waterfront also solidified the reputation of the Actors Studio as a training ground for a new generation of American actors and familiarised audiences with the ‘Method’ – an acting style that emphasised psychological realism rather than the more declamatory methods taught in British acting schools. As Christina Pickles, then a student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA), remembers it:

We cut Rapid Diction class to go see the film. It was a revelation. We immediately went back to an empty classroom, where Brian Bedford and I tried to improvise a scene. We had never done that kind of thing before and we had certainly never been taught it.

Dealing with corruption on the New York–New Jersey docks, On the Waterfront was also a social problem film of a sort that seemed to have become outmoded in the golden sun of 50s’ American prosperity. Yet at the same time it was severely criticised by the left in America (and England) for what they considered to be its vindication of informing, when the hero Terry Malloy finally decides to testify against the corrupt union leader. This was a volatile issue because Kazan, Schulberg and costar Lee J. Cobb had all testified as friendly witnesses to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), naming names of former Communist associates. Upset by Kazan’s testimony, Brando, whose career had been launched by Kazan in A Streetcar Named Desire, twice returned the script unread, until the producer Sam Spiegel persuaded him to take the part.

On the Waterfront thus has an important place in the careers of Kazan and Brando, two of the most significant figures in American film and theatre of the 1950s. Its showcasing of Method acting had a tremendous influence on both American and European performance styles as well as plots. Its political issues and the controversies around its production mirror the conflicts of the Cold War and the anti-Communist paranoia gripping the United States.

Yet the complexities of the film belie any easy equation between the political beliefs of its creators, the actions of its characters and the shape of its plot. Within the film itself is a kind of ambivalence about moral behaviour (figured visually in the constant mists of the Hoboken waterfront) and the difficulty of moral choices that gives it a resonance beyond the partisan politics of its day.

Like so many heroes of the period – J. D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, Jack Kerouac’s Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, or the characters played by James Dean and Montgomery Clift in a variety of movies – Brando’s Terry Malloy is a young man trying to find out how to grow up. This is another chord that On the Waterfront strikes in the postwar world – the appeal of the anti-hero. He is not the traditional hero whose easy choices and actions make the world whole but a newer sort of protagonist whose actions illustrate the difficulty of maintaining one’s identity and integrity amid the world’s incoherence. Instead of neatly tying up all conflicts in a balanced resolution, the end of On the Waterfront, so notoriously attacked in Lindsay Anderson’s Sight and Sound essay soon after it appeared, leaves its issues unresolved and still disturbing.

In fact, it is tempting to argue that naming names before the HUAC put Kazan into a moral and psychological quandary that paradoxically made him a better director. Comparing the moral questions – and the visual style – of his previous Oscar-winning film Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) with On the Waterfront is instructive. Gentleman’s Agreement is all evenly lit moral clarity: anti-Semitism is wrong; Gregory Peck is our reporter–hero for exposing it by pretending he is Jewish, although he is never really in jeopardy himself. On The Waterfront is much more ambivalent: Terry Malloy seems to move from the corrupt world of the gang of union thugs to the moral high ground of testifying about Joey Doyle’s murder. But at the end, a bloody and beaten symbol of resistance to the mob, he is as much manipulated by Karl Malden’s Father Barry as he had been by his brother Charley and gang boss Johnny Friendly. In his own preliminary notes about the character, Kazan identifies Terry’s mixture of shame and bravado with his own compound of immigrant striving and energy, coupled with a resentment about his efforts to be ingratiating before his testimony alienated him from old associates and friends: ‘Yourself during Waiting for Lefty – or when you were the white-haired boy-director. With what pride you used to walk around! – with what confidence!! … He’s the last person the mob would expect to have any trouble with.’ As Kazan often remarks to himself in these notes, despite his undergraduate study at Williams, the prestigious New England liberal arts college, despite his time in the Group Theatre, one of the most celebrated and influential theatre companies of the 1930s, and despite his resounding successes in both film and theatre, he still felt perpetually outside, a position that his HUAC testimony had only confirmed. ‘I despised my nickname … Gadget! It suggested an agreeable, ever-compliant little cuss, a “good Joe” who worked hard and always followed instructions. I didn’t feel that way, not at all.’1

The Lure of the Waterfront

Born in Istanbul in 1909, Kazan emigrated to the United States with his family in 1913. After attending Williams College and Yale Drama School, he joined the embryonic Group Theatre, one of the many amateur and professional leftwing arts groups of the 1930s. It was destined to become the most influential because of its intense commitment not only to political content but also to elaborating for American performers the theories of acting developed by Constantin Stanislavsky for the Moscow Art Theatre.

At first an actor and assistant stage manager, Kazan continued to act in theatre and films up till and through 1941, but gradually concentrated more of his energies on direction. In 1942 he had a great success on Broadway with Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth and in 1945 directed his first film A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, for which two of the actors, James Dunn and Peggy Ann Garner, received Academy Awards.

Kazan was building an enviable reputation not only as a director with a special sensitivity to acting but also one who worked closely with playwrights. In 1947, along with Robert Lewis and Cheryl Crawford, who had been fellow members of the Group Theatre, he co-founded the Actors Studio to furnish a place where American actors could work on their craft. 1947 was also a big year for Kazan professionally. On stage he directed Arthur Miller’s All My Sons and Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. On film, he directed Sea of Grass, Boomerang!, and Gentleman’s Agreement. Streetcar received the Pulitzer Prize and Kazan won the directing Academy Award for Gentleman’s Agreement. The next year on Broadway he directed Lee J. Cobb in Miller’s Death of a Salesman, which also received the Pulitzer Prize.

Death of a Salesman, Mildred Dunnock, Arthur Kennedy, Lee J. Cobb as Willy Loman (speaking), and Cameron Mitchell

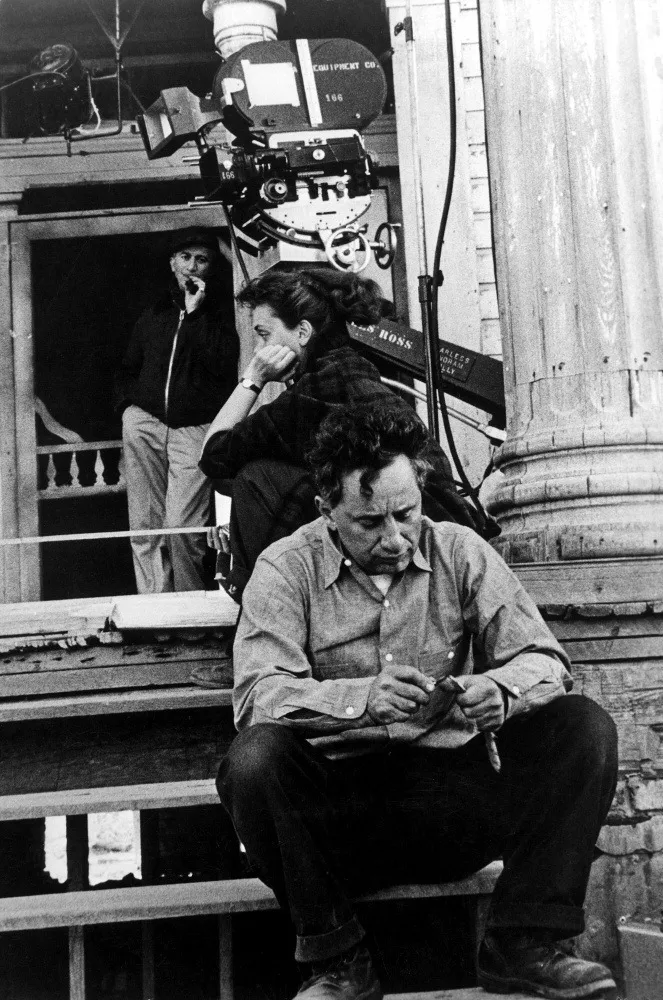

Elia Kazan on the set of Baby Doll (1956)

Kazan, Brando, Julie Harris, and James Dean on the set of East of Eden (1955)

Meanwhile, in late 1947 Arthur Miller was frequenting the Red Hook section of Brooklyn doing research for a script that would deal with crime and corruption on the waterfront. As he tells the story in his autobiography Timebends, he had been inspired by the tales of a rebel leader named Pete Panto who had battled the gang-run unions. Panto was a young union activist who had been murdered in 1939 but whose name was still written in graffiti on neighbourhood walls: Dov’é Pete Panto? Where is Pete Panto? ‘The idea of a young man defying evil and ending in a cement block at the bottom of the river drew me on.’2

Since Kazan was looking for a film project as well, he and Miller decided to work together. But when the script, now called The Hook, was finished and they went out to Hollywood in 1951 to try to sell it to Columbia, they met a stone wall.3 HUAC had held hearings in Hollywood in 1947, issuing subpoenas to forty-three members of the Hollywood community. A group dubbed the ‘unfriendly 19’ chose not to co-operate with HUAC on First Amendment grounds. Of these nineteen, ten ...