![]()

1 THE APPRENTICESHIP, 1948–54

Hudson’s first screen performance was as an uncredited, supporting player in the role of an air corps officer in Fighter Squadron (1948). It has become part of his popular legend that, with only three lines of dialogue, the young actor had taken anything between twenty and thirty-eight takes (depending on which source you choose to believe) to successfully deliver his lines, much to the frustration of the famously brusque director Raoul Walsh. This frequently recounted incident has, in many respects, tended to set the tone in terms of the critical reception of Hudson’s subsequent screen performances.

Chosen primarily for his physical appearance and disparagingly referred to as ‘good scenery’ by Walsh who, as we will see in this chapter, had a significant role in fashioning his star image and his emergent performance style, Hudson has frequently been caricatured as a weak actor (Moss 2011: 281). For example, in a documentary about the star, fellow contract player William Reynolds notes that, in the early years of his career, ‘I don’t think that many of us thought he was that much of an actor … I don’t think my opinion of Rock was of an actor of any great moment. I thought he was awkward at times.’1 This is an opinion, however, that Reynolds suggests he was to eventually revise. Similarly, Robert Stack, who appeared in Fighter Squadron with Hudson, remembers Walsh describing Hudson as a ‘silly, black haired goon’. Jack Larson, the star of Fighter Squadron, remembers Hudson’s stage fright and on-set nerves, which would evidently account for the untrained novice’s performance. According to Larson, he ‘would stumble, would gulp, would forget the lines, he wouldn’t come in. It was an unbelievable situation.’ This characterisation of Hudson’s acting extends itself to film scholarship. In an essay on Hudson and Day’s collaborations, Foster Hirsch describes Hudson in his early roles as demonstrating ‘no discernible acting skill whatsoever’ as ‘the wooden new actor with the trick name’ and perhaps most critically that ‘Hudson still didn’t seem to grasp what it took to create the semblance of a human being on film’ (2010: 157). This kind of dismissive summary of Hudson’s work and the wider concomitant debate around the nature and quality of Hollywood film acting is a subject that we will return to on more than one occasion in this book.

As I have indicated in the Introduction, at least one of the objectives of this book is to recuperate Hudson’s reputation as an actor and, in so doing, to both reappraise and situate his performances within a context that might account for them. This chapter deals ostensibly with the material upon which many of the charges of bad acting are largely based and is an attempt to challenge (or at least question) the orthodox view of Hudson’s acting prowess. This means focusing attention on a series of early performances in a range of genre films of variable quality and intent. My contention here is that this is the period where we are able to witness the developmental stages of a performance style, largely through a process of trial and error. This involved experimentation with different styles, registers and material as key personnel in the machinery of the Hollywood studio system (including agents, producers, directors and the actor himself) worked to establish what would become Hudson’s screen image.

The period between 1948 and 1954 can, in many respects, be regarded as Hudson’s apprenticeship as a screen actor. Unlike some of his peers (such as Robert Stack, Natalie Wood, Elizabeth Taylor) Hudson was not a child actor and had almost no prior training as an actor before pursuing a career in cinema. Nor did he come to prominence with a spectacular early performance. His development as an actor was instead gradual and incremental. Hard work and perseverance were the significant drivers of his career development and are also key factors in an understanding of what was to become his star image/persona. The embodiment of the American dream that success might be gained through a strong work ethic, combined with athleticism and clean living, Hudson was to speak very directly to the values of postwar America.

The screen test for Twentieth Century-Fox (1949)

One of the earliest fragments of film to feature the aspiring actor is a screen test for Twentieth Century-Fox made in July 1949, directed by Richard Sale. The test features the twenty-four-year-old Hudson, identified as spending one year at Warner Brothers (during which time he had appeared in Fighter Squadron) paired with Kathleen Hughes, a contract player for the studio, notable for her role in low-budget Universal kitsch classics such as It Came from Outer Space (1953) and Cult of the Cobra (1955). Hughes, who also secured a contract from Universal, would subsequently work with Hudson again on The Golden Blade (1953). As with his earlier bit part in Fighter Squadron, this footage has assumed a popular legendary status as the epitome of an unsuccessful screen test and, paradoxically, a demonstration that persistence and endeavour can triumph over all, even a deficit of talent. As Sara Davidson notes in Rock Hudson: His Story, ‘one of the tests is still shown by Twentieth Century-Fox to young actors as an example of how bad one can be and still, through hard work, become a star’ (Davidson and Hudson 1986: 45).

The purpose of any screen test is to simultaneously assess an actor’s dramatic range, the ability to occupy and move through space and how he or she looks in a range of potential dramatic situations, camera angles, lighting set-ups and arrangements. The scene for the Twentieth Century-Fox test is the lounge of a glamorous apartment. Hudson hurriedly prepares the room and dresses for a rendezvous with Ellie (played by Hughes). He rushes around, preparing the room, drawing attention to his physical stature and his gangly, awkward arms as he moves from the front to the back of the set. He sets out glasses and evidently struggles to uncork a bottle of champagne before rushing to throw on a jacket and answer the door to Ellie. Rather than the suave sophisticate that his handsome features might imply, he appears to be the gauche young man from the midwest that at this point he was. Notably, Raoul Walsh, who was to cast him in several Westerns, had thought that, rather than presenting him as a man of action, this kind of setting and role would suit him better: ‘at the time I saw him he was going on the soft side; I suggested he watch Cary Grant’ (Moss 2011: 281). While Walsh may well have been correct in the long run, at this point there is little evidence in the frantic and ‘action-packed’ way that he moves around this sophisticated setting of the urbane man about town. The awkwardness of these opening seconds is further emphasised as his guest arrives. Panting nervously before he even opens the door, he delivers the line, ‘Ellie, I knew you’d come back’, leaving no time for Hughes to deliver her own response, ‘Hello Bick’, before he grabs her by the left arm and appears to push her into the room, snatching her coat and purse from her and throwing them onto the couch before pulling at her arm to ‘celebrate with champagne’. As the camera pans into a midshot of the couple, an exchange takes place that is the motivation for the scene. Ellie has had to consider her relationship with Bick and he has been anxiously awaiting her return. The scene then places Hudson as the vulnerable partner in this encounter and demands that the actor modulate his performance as our comprehension of the dynamics of their relationship becomes clearer. Moving to the couch and into a medium close-up, Hudson has to turn away from Hughes to deliver a moment of reflection that is designed to suggest Bick’s reminiscence of his wartime experience, while the camera zooms into a close-up. This sequence of reverie and emotional unburdening is abruptly disrupted by an unexpected phone call that provokes Ellie’s suspicions. Her concerns are then dissipated when the caller is revealed to be from the local delicatessen. The scene closes with an obligatory kiss.

The scene therefore requires a demonstration of a range of emotions and changes in tempo and delivery in the space of just over two minutes, from anticipation and urgency, to reflection and emotional appeal, to suspicion and uncertainty and, finally, to humour and romance. The results of the test undeniably have comedy value (albeit unintentionally). Hudson fumbling with the buttons of his jacket, yanking the hapless Hughes into the room, his lightning change from pensive reverie at his war experience to confessions of love, all inevitably provoke laughter from the modern viewer. Nevertheless, the scene asks a lot of any actor, especially an inexperienced novice such as Hudson. As Andrew Higson notes in an essay on film acting, ‘Crucially, what determines the scope of the actor’s facial, gestural and corporeal register are the details of framing, angle and distance of shot and focus …’ (2004: 153). Given that this is the case, the assessment of Hudson’s skills at this stage in his career as meagre or lacking seems to me unduly critical as he demonstrates the capacity to scale his performance according to the constraints of the cinematic frame, a technique that some actors can take a considerable amount of time to perfect. It is quite true to argue that he does not yet occupy space and move with confidence through a scene. However, his ability to respond and to react to another actor’s performance is already in evidence. Just as importantly, as Sirk noted, ‘the camera sees with its own eye’ and the specifics of Hudson’s physicality and in particular his adeptness at conveying vulnerability (while simultaneously remaining resolutely masculine) is both an appealing and also a rather unsettling quality (Halliday 1972: 86). It can scarcely be disputed that he appears clumsy in the early part of the test. In part, at least, this is due to the quite complicated blocking of the scene, demanding a level of nervous activity that then needs to be toned down significantly for the medium close-up dialogue sequences. It is in the more ‘romantic’ elements of the test that Hudson’s potential manifests itself. Notwithstanding the rather hilarious shift between a recollection of war and his profession of love for Ellie (accompanied by a deep intake of breath and rapid turn of the head), Hudson’s good looks (filmed in close-up and medium shots), deep yet soft voice and open expression are ideal for the role of the romantic lead. It is in this part of the test that his skill in handling this kind of close camerawork reveals itself. At this early point in his career, Hudson demonstrates performative qualities that transcend his material, doing so even within the context of a screen performance that has often been held up to ridicule.

In Star Studies: A Critical Guide, Martin Shingler identifies photogeny (i.e. good looks) and phonogeny (i.e. a pleasing voice) as far from superficial considerations in an understanding of the qualities that could garner an actor a successful film career. At six feet and four inches in height and with dark wavy hair and classically uniform features, Hudson embodies (as I will discuss in the next chapter) the, albeit clichéd, ideal of the ‘tall, dark and handsome’ man. Consequently, his physical beauty, which (while culturally and socially specific) has stood the test of time, positions him as an ideal candidate for a pretty diverse range of roles. Shingler also notes that good looks can entail some less positive consequences, observing the ‘ambivalences and insecurities of beauty, raising questions about the way in which excessive beauty can be limiting for a film actor in terms of restricting the types of roles they are allowed to play’ (2012: 74). Hudson’s good looks and his status as ‘good scenery’ have undeniably often taken attention away from a consideration of his performances in critical accounts. Indeed in his early screen appearances he was cast because of his physical attributes rather than anything else. Furthermore, I would argue that Hudson’s physical and (perhaps more specifically) his facial beauty has rarely been regarded as contributing in a positive sense to the creation of his performances, with the possible exception of Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966). In short, his good looks often conspired against him as far as a critical reputation goes. I think it is also interesting to note that, even while his potential for playing romantic roles was clear even from this early stage, he was in fact rarely cast in such roles at the start of his career. Indeed, as we will see in the second chapter, it is not until this aspect of his range was fully exploited that he was to achieve star status.

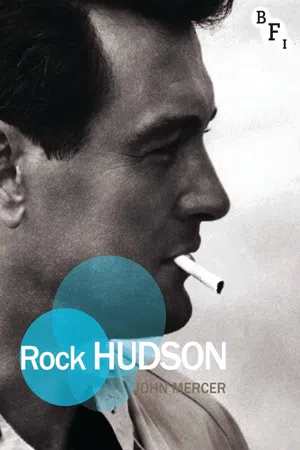

Hudson’s famously unsuccessful screen test reveals signs of early promise

The role of the agent: Henry Willson

The years between 1948 and 1954 are also the period during which a group of industry professionals who all made an investment in Hudson as a commodity, worked collectively to shape their actor’s image and to identify what he represented. The principal figures in this process of development include the agent Henry Willson, the director Raoul Walsh and latterly the producer Ross Hunter and the director Douglas Sirk, both of whom will be discussed in the subsequent chapters of this book. This period should be understood as the point in Hudson’s career when the type of actor he would become and the specifics of his performance style were as yet undecided. Just as importantly, what Hudson represented in terms of a model of masculinity was likewise in a state of flux. This was then the stage of his career when the young actor and those around him were developing the idea of ‘Rock Hudson’ as an actor and personality and also trying out ‘versions’ of Rock Hudson on audiences.

Probably the first key player (after Roy Fitzgerald himself) in the process of formulating Hudson’s image was the Hollywood agent Henry Willson, who was what would probably be described as a Hollywood ‘insider’. His father had been the president of Columbia Records in New York and the young Willson had moved to the West Coast and started his career as a writer for the Hollywood Reporter before becoming an agent for Zeppo Marx in the late 1930s. He came to prominence by launching the career of Lana Turner and worked as a talent scout for David O. Selznick. By the 1940s, Willson had established his own agency, handling the careers of many of the major actors of the time, including Lana Turner, Jennifer Jones, Natalie Wood and Dorothy Lamour. He was also, by the late 1940s and early 50s, operating in an industrial context that was coming to an end. Tom Kemper, in his forensic examination of the emergence of the agent during the 1930s and 40s, has observed that the 50s ‘marks the rise of the agents, when corporate agencies were supplanting agencies built around the personality and connections of one or two individuals’ (2010: xiii). Willson, who was notoriously ruthless in his own personal ambition and in his endeavours to promote his clients, belonged then to an often nepotistic and increasingly outmoded mechanism for managing and casting actors in productions.

As is almost always the case in the biographies of Hollywood stars, provenance is something of a contested territory and there are at least three versions of how Willson first met the aspiring actor Roy Fitzgerald, who would become Rock Hudson, starting with the story of a chance encounter in the postroom of Selznick Productions where Fitzgerald was a delivery boy. An alternative version suggests that Fitzgerald, working as a truck driver, was much more proactive in making contact with industry professionals; for example, by having professional photosets produced and hanging around studio backlots in the hope that his good looks would be noticed (Hofler 2005). Willson’s homosexuality was well known in Hollywood and, although accounts of Willson’s and Hudson’s past are frequently contradictory and unreliable, it also seems that, at the start of his career, the young actor’s homosexuality was not the scrupulously maintained secret it would become just a few years later. Indeed, most accounts seem to suggest that Roy Fitzgerald made use of both his sexuality and his good looks to gain introductions and was a familiar figure in the Hollywood gay milieux.2

Whichever version of events is true, Willson quickly identified the young man as enjoying the kind of physical attributes that would entitle him to a place on his growing roster of young male actors. Furthermore, most accounts confirm the importance of Willson’s role in the orchestration of Fitzgerald’s transformation into a major Hollywood star. This process of course is made manifest by the act of naming and it is Willson (although once again accounts differ) who came up with the name Rock Hudson. Providing names for his clients was something that Willson had a particular instinct for, choosing appellations that seemed p...