eBook - ePub

César

About this book

Bringing to a close his 'Marseille' trilogy, César (1936) was one of Marcel Pagnol's most significant projects. This text reviews the questions that Pagnol posed in the film, looking at how he reflected the contemporary and artistic culture of the city, around which the trilogy was based. Above all, Stephen Heath looks at César 's relation to the contemporary artistic and cultural-historical reality of Marseille, the defining locality of the trilogy and in many ways its main character.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

PAGNOL, CINEMA

Life

As he liked to recall, Pagnol was born in the same year as the cinema, within a few February days of the Lumière brothers' registration of the patent for their cinematic apparatus in 1895. His birthplace was Aubagne, a small town ten miles inland to the east of Marseille, where his instituteur father taught at the local school. Two years later, the family moved to the outskirts of Marseille and then in 1900 to the centre of the city itself where Pagnol grew up, spending childhood summers in La Treille, a village in the hills to the northeast – summers evoked in his memoirs La Gloire de mon père and Le Château de ma mère, widely known as a result of Yves Robert's 1990 film versions. After his primary schooling, he attended the Lycée Thiers (the location for his 1935 film Merlusse) where in 1914, with a group of friends he founded a literary review, Fortunio; short-lived in its first and second series, it was successfully relaunched in 1921, eventually becoming the influential Cahiers du Sud (though Pagnol's involvement had ceased before then). In the second series, Pagnol published two sonnets by another young Marseillais also to have a – very different – theatre and cinema career: Antonin Artaud.

After gaining a degree in English from the Université de Montpellier, Pagnol followed in his father's footsteps and became a teacher. He taught in schools in Tarascon, Aix and Marseille, until in 1925, at the age of thirty, he was given a post in the Lycée Condorcet in Paris. To reach the capital had long been his goal and this for reasons not of academic but of literary ambition. In 1927, he duly abandoned teaching to concentrate on making his breakthrough as a writer. This came the following year with the success of his play Topaze; a social satire in which a modest teacher is caught up in the world of business and gets the better of those seeking to manipulate him, but at the cost of the moral principles he had once sought to instil in his pupils. The success was confirmed a year later by the theatrical triumph of Marius and by the spring of 1930, the two plays together had totalled over a thousand performances in Paris alone. Such popular success was to accompany Pagnol throughout his career, and the more so after his turn to cinema.

Pagnol's interests and activities beyond his plays and films were multiple: translating Virgil and Shakespeare went along with attempts to prove Fermat's last theorem; skills at making things led to numerous inventions, some of which he patented, some of which were ingeniously improbable (an emergency braking system dependent on a giant foot dropping down to lift a car's wheels off the ground). Important for his cinema career was precisely this ability to turn his hand to anything and his determination always to succeed. Creative, commercial, practical and persuasive talents combined in a way that was decisive for the accomplishment of the turn to cinema.

In the first years of World War II, Pagnol continued his cinematic activities in Marseille (Marseille being in the 'free zone', not until late 1942 under German occupation), finishing La Fille du puisatier (1940), which had been interrupted by the outbreak of war, and beginning what was announced as his 'second trilogy', La Prière aux étoiles. Like the first, this was to comprise three films named after the three main characters but set mostly in Paris and in a quite different social milieu. The project was abandoned early in 1942 to avoid the films falling into the hands of the German-controlled Continental Film company, set up to run production and distribution in the occupied zone and increasingly exercising authority beyond it. One of the films had been more or less completed but Pagnol physically destroyed the copies (accounts, including Pagnol's own, vary as to how complete the destruction was and fragments survive; what I have seen of them, together with the published script, suggests that this second trilogy would have been embarrassingly bad).

The Liberation saw him in Paris at the head of a 'purification committee' established to look into the wartime activities of dramatic authors and composers, which he wound up quickly and painlessly. In 1942, given the situation in France, he had refused to stand for election to the Académie française but he agreed and was elected in 1946; an election heralded as that of 'the first Academician of cinema'. He died in 1974 and was buried in La Treille. The funeral oration was given by René Clair, himself by then a fellow member of the Académie and a long-standing friend, despite their sharp public exchanges in the 1930s over the introduction of sound.

Into Cinema

At the beginning of the 1930s, Pagnol was a powerful presence in French theatre; by the end of the decade, he had become a powerful presence in French cinema. The moment is important: Pagnol's encounter with cinema was with the new talking pictures. Previously, he had shown little interest in film, not much beyond a couple of dissatisfied pseudonymous reviews in Fortunio and some half-hearted attempts to have a film made of an early play about boxing written with a friend (it eventually became Roger Lion's 1932 Direct au cœur). The advent of the talkies coincided with Pagnol's success as a playwright and it was this coincidence that prompted his quick enthusiasm. A recent arrival in the theatre world, he was without the prejudices of many established dramatists and more readily open to the possibilities of the new medium; coupled with which, his reputation facilitated his entry into cinema – he was after all the hot theatrical property of the day.

In characteristic anecdotal style, Pagnol many times described the encounter with cinema. Dining in a restaurant in Paris one spring evening in 1930, he was greeted by the actor Pierre Blanchar just back from London and full of the experience of seeing – and hearing - a talking film: 'the illusion is perfect, it's hallucinatory'. The film was The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont, 1929), featuring Bessie Love and showing at the London Palladium. Pagnol went to London the next day, saw the film three times, and returned to Paris 'enflamed with theories and projects'. He had no doubts: the future lay with the talking picture as 'the new mode of expression of dramatic art'; a conviction immediately proclaimed in an article for the newspaper Le Journal published under the title: '"The talking film" offers the writer new resources'.

The decisive first step towards Pagnol's appropriation of these resources was his meeting with Robert T. Kane, head of Paramount's European production arm, which had sound studios on the outskirts of the capital in Saint-Maurice where standardised versions of American films were made simultaneously in different languages for the various national markets. Kane appointed Pagnol to head an ephemeral 'literary committee' of French writers (Kane's relation to literature is summed up by his demand one day that the poet Verlaine, thirty years dead, be brought to his office immediately). More importantly, he allowed access to the studios where, with nothing particular to do, Pagnol spent his time moving from department to department, learning all he could about cinema. This apprenticeship was vital: 'If, later', he insisted, 'it was possible for me to make films, while at the same time directing a laboratory, studios, and distribution agencies, I owe it to the friendship of Robert T. Kane.'

Kane had acquired screen rights to the play Marius, the film of which would be by far the most successful of Paramount's small number of original European productions. Alexander Korda was brought in to direct, Pagnol provided the adaptation, and the film was shot in five weeks in 1931 (Swedish and German versions were shot at the same time, the German version also directed by Korda). The shooting was Pagnol's second apprenticeship: 'Korda taught me cinema'. The two worked closely together, the master of silent cinema alongside the master of theatrical speech. The resulting film was a box-office triumph.

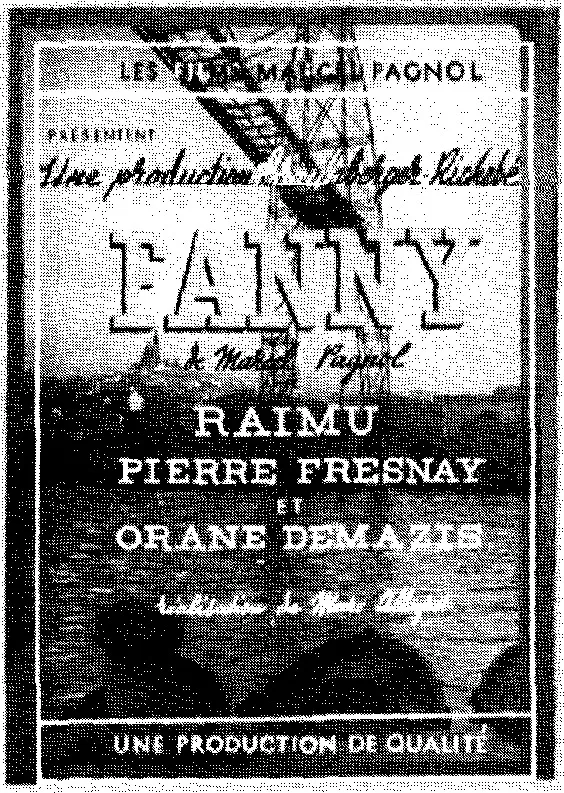

Paramount also had the screen rights to the play, Fanny but Kane released them, apparently believing that the success of Marius had exhausted the commercial potential of the Marseille comic-drama vein. In 1932, therefore, Pagnol joined forces with producer and distributor (and soon-to-be director) Roger Richebé, a fellow Marseillais, to form a company to make Fanny (Richebé's parents had opened one of the very first cinemas in Marseille, guaranteeing popular success – the cinema was called Le Populaire – by pledging that tickets would never cost more than a glass of beer). Pagnol adapted the play and, on Richebé's advice, gave the direction of the film to Marc Allégret, though himself participating actively in the shooting, much to Allégret's exasperation. Not that the tensions impaired the film's success, which was greater even than that of Marius.

Pagnol with French and Swedish Fannys (Orane Demazis and Inga Tidblad)

In the early 1930s, Pagnol's cinematic activity went well beyond involvement in those two films. He provided scenario and dialogue for a number of films not based on his own work (including one of the first directed by Richebé, L'Agonie des aigles, 1933) and began his own career as a director, making films both from his adaptations of works by others (notably Jofroi, 1933, and Angèle, 1934, from stories by Provençal novelist, Jean Giono) and from his own original film scenarios (Cigalon and Merlusse, both 1935). Just prior to César, he directed an adaptation of his play Topaze, dissatisfied as he was with the 1932 Louis Gasnier version for Paramount (Pagnol's version, in which Sylvia Bataille had a role, was not much better and he withdrew the film). It was thus with some substantial directing experience that in 1936 he took on César. Fundamental too in these years of the move into cinema was his desire not only to make films as author–director but to do so with control over every aspect of the film-making process; this being the prerequisite for authorship of what would then truly be his films. The money earned from his plays and the first two trilogy films was used to this end and in the space of a very few years the goal was achieved: Pagnol owned his means of production.

After Fanny, with a group of friends and fellow dramatists, he had set up in 1933 a production and distribution company called – alluding to United Artists – Les Auteurs Associés, which aimed to offer creative independence from the hold of the major producers. This was wound up the following year to be replaced by the Société des Films Marcel Pagnol, with Pagnol henceforth responsible to no one but himself. Along with this went the establishment of his own production facilities in Marseille: first, a small studio coupled with a processing lab, ready in 1934 in time to provide support for Renoir's Toni; then, with the acquisition of disaffected warehouses nearby, a substantial complex with several stages, editing and viewing rooms, and administrative offices, with the processing lab taking over the space of the initial premises; the whole set-up completed in 1938 for the shooting of Pagnol's own La Femme du boulanger. He also acquired cinemas in Marseille – one in 1938 was called, naturally enough, Le César (still there today).

Advertisement for Pagnol's film laboratories in the Indicateur Marseillais, 1936

He had guaranteed his freedom: 'I was the first in France to be free as a film-maker.' The claim is not vain: in the course of the 1930s he effectively secured the possibility of making his own films much as he pleased from start to finish. He also thereby became a serious player in the French film industry, this in the face of the resources and dominance of the capital. Marseille's distance from Paris was not unimportant in this, nor were the conditions of climate and light, nor again were the city's connections with cinema's history – the train arrived, after all, in nearby La Ciotat and a number of early Lumière films were shot in Marseille itself. The city had quickly been an important centre for film production; the Marseille-based Phocéa-Film company in particular enjoyed national success in the 1920s before ceasing activity in 1930, unable to manage the transition to sound. With its open-air studios and other facilities, the city was indeed often described (hyperbolically, but nevertheless) as 'the French Los Angeles'. Pagnol gave renewed meaning to that description and the importance of Marseille and the significance of Pagnol's studios were consolidated for a while by the German invasion of France and the city's situation in the free zone with, at first, fewer restrictions on film production.

Those who worked with Pagnol in the 1930s stress the special atmosphere of his studios; an atmosphere far from – and not just physically – that of the large Paris-based companies with the kind of hierarchical organisation that Pagnol had encountered at Paramount and which he satirised in his film Le Schpountz (1938). The word invariably used to characterise Pagnol's set-up by those who were directly involved is 'family' – they were, they say, members of 'la famille Pagnol' – and the impression given is of an organisation that was paternalistic, artisanal rather than industrial, out of line with standard industry practices (Renoir even talked of it as 'medieval'). Reports have it that everyone did everything and that divisions between categories of technician and between actors and technicians were never rigid (so Albert Spanna, an electrician on the set of César, also appears in it as the Postman). Games of bowls were an indispensable feature of the working day and everyone gathered for lunch to exchange ideas and suggestions: 'we discussed things and decided what we were going to do that afternoon', Pagnol many times recalled.

Doubtless there is truth in all this – it is hardly surprising that working in the Studios Marcel Pagnol in Marseille was a different experience from that of working in the Paramount studios in Saint-Maurice. It remains nevertheless that Pagnol was running a commercial company making commercial films for the French market. His work methods were effective not because they were pre-industrial (they were not) but because they were able to include the creation of such an atmosphere as part of the management of the production of his films. The reality was, in his words, that he was 'master in his own home', that he was involved in and in control of all departments of the 'familial' enterprise. He had something to which later French film-makers – Godard and Truffaut most explicitly–would look back in envy: a production situation in which nothing was out of his hands.

This independence and authority allowed him very substantial authorship of his films and Pagnol might be seen as the film-maker–author par excellence. His own stated conception of authorship in cinema, however, played down the film-making process and stressed writer over film-maker, denying authorship to the latter. The experience at Paramount had convinced him that for Hollywood the writer was bottom in the hierarchy of those concerned in the making of a film; whereas for him, the writer should be at the top as the very source of cinematic creation: 'it is the creation of what is going to be shot that makes one an author'. Thus Orson Welles – Pagnol's example – was the autho...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Pagnol, Cinema

- 2 The Marseille Trilogy: Synopses

- 3 'César'

- 4 Marseille

- Conclusion

- Credits

- Bibliographical Note

- Picture Credits

- Bm

- Bm 2

- Bm 3

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access César by Stephen Heath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.