- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Blade Runner

About this book

Ridley Scott's dystopian classic Blade Runner, an adaptation of Philip K. Dick's novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, combines noir with science fiction to create a groundbreaking cyberpunk vision of urban life in the twenty-first century. With replicants on the run, the rain-drenched Los Angeles which Blade Runner imagines is a city of oppression and enclosure, but a city in which transgression and disorder can always erupt. Graced by stunning sets, lighting, effects, costumes and photography, Blade Runner succeeds brilliantly in depicting a world at once uncannily familiar and startlingly new. In his innovative and nuanced reading, Scott Bukatman details the making of Blade Runner and its steadily improving fortunes following its release in 1982. He situates the film in terms of debates about postmodernism, which have informed much of the criticism devoted to it, but argues that its tensions derive also from the quintessentially twentieth-century, modernist experience of the city – as a space both imprisoning and liberating.

In his foreword to this special edition, published to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the BFI Film Classics series, Bukatman suggests that Blade Runner 's visual complexity allows it to translate successfully to the world of high definition and on-demand home cinema. He looks back to the science fiction tradition of the early 1980s, and on to the key changes in the 'final' version of the film in 2007, which risk diminishing the sense of instability created in the original.

In his foreword to this special edition, published to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the BFI Film Classics series, Bukatman suggests that Blade Runner 's visual complexity allows it to translate successfully to the world of high definition and on-demand home cinema. He looks back to the science fiction tradition of the early 1980s, and on to the key changes in the 'final' version of the film in 2007, which risk diminishing the sense of instability created in the original.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Filming Blade Runner

Pre-production

The irony is that Philip K. Dick never got to see Blade Runner. Dick was one of the most prolific and brilliant of science fiction writers. His work is thoroughly paranoid and simultaneously witty and frightening, filled with slips of reality that are often only imperfectly repaired by story’s end. In his earlier career, following unsuccessful attempts to succeed in the mainstream literary market, Dick began turning out pulpy science fiction tales in which different levels of reality continuously bumped up against each other, with a hapless protagonist struggling in the spaces between. A hallucinatory quality began to pervade the novels, and discussions of (and evocations of) psychosis and schizophrenic breakdown became increasingly prominent. Androids, mass media and religion all produced false realities, worlds of appearance that began to fall apart along with the minds of the protagonists. Drugs and psychosis, which both had their place in Dick’s history, were frequently conduits to another reality, perhaps more real and perhaps not.

After decades of labour, Dick had achieved significant critical, if not financial, success in the United States – even more in France. His agent had sold the rights to his 1968 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in 1974, but nothing was ever produced. As early as 1969, Jay Cocks and Martin Scorsese (who would collaborate in 1993 on The Age of Innocence) expressed interest, but the project got no further. In the mid-1970s, Dick himself flirted with cinema, adapting his superb novel UBIK into a screenplay for Godard’s sometime collaborator, Jean-Pierre Gorin. The screenplay was good too. Dick considered his new medium carefully: he wanted his film to end by regressing to flickering black and white silent footage, finally bubbling and burning to a halt. Once more, the project remained unproduced.

At about the same time, another writer began to wrestle with Androids, trying to fashion a screenplay from its diverse materials. Hampton Fancher was an actor and independent film-maker who aspired to produce for Hollywood. He was attracted by the novel’s saturated air of paranoia and also, not incidentally, by its potential as an urban action film. The novel was optioned for Fancher by the actor Brian Kelly, and Kelly approached producer Michael Deeley, who was intrigued by the book, but not by its cinematic potential. Deeley suggested that a screenplay be prepared, and Fancher found himself, reluctantly, tagged as writer. The initial draft was completed in 1978, and Deeley began to shop it around.

Deeley had worked as an editor on The Adventures of Robin Hood, a television series produced in Britain, and first worked as a producer on The Case of the Mukkinese Battlehorn (1956), a stilted but occasionally inspired piece of Goonery with Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers. By the time Kelly and Fancher approached him, he’d gained some experience with science fiction, having produced The Wicker Man (1973) and The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). Deeley had headed British Lion and Thorn-EMI, and also produced Peter Bogdanovich’s Nickelodeon (1976) and Sam Peckinpah’s Convoy (1978). His major critical success came with Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, which received the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1978.

Deeley approached Ridley Scott, a former set-designer for the BBC who had directed episodes of Z-Cars and other programmes for British television before producing hundreds of commercials, many strikingly stylish. His first feature was The Duellists (1977), an adaptation of a Joseph Conrad story, and a very effective blend of naturalistic and stylised elements. His next work, Alien, was in post-production: it would turn out to be a charged telling of a familiar story. Already Scott’s hallmark was a visual density that revealed as much as, or more than, the script. The characters inhabited complex worlds that provided oblique contexts for their decisions and actions. There could be, in Scott’s best work, no psychology without an accompanying sociology, no individual in isolation.

At first, however, Scott declined the project. He was committed to a number of large-scale assignments, including Dune (1984) for Dino de Laurentiis (David Lynch finally directed Dune which, despite its strengths, is a case-study in how not to adapt a popular science fiction novel), and was understandably resistant to being typecast as a science fiction director. But personal difficulties led him back to Blade Runner, a project that he hoped to begin immediately, although it would be fully a year before shooting could commence. Scott joined the production in late February 1980.

As all this was going on, Star Wars was released. Before its appearance, science fiction was not a commercially viable Hollywood genre. The lively matinees of the 1950s were the stuff of the past, and science fiction cinema in the 1960s and 70s had provided a mix of modernist obscurity (Alphaville, 1965, 2001, Solaris, 1972, The Man Who Fell to Earth) and Saturday-afternoon dystopianism (Soylent Green, 1983, Logan’s Run, 1976, Westworld, 1973). The expansionism that once almost defined the genre had yielded to collapse, implosion and the overwhelming sense of a future of exhausted possibility.

Dystopia by firelight

Star Wars opened in May 1977 and quickly became one of the most popular films in Hollywood history. While its initial success was predicted by no one, the history of this saga exemplified the strategies of the post-classical Hollywood film industry. In 1975, Jaws had remade the marketing wisdom of Hollywood by finding and exploiting a summer audience with uncanny dexterity. Star Wars reaped the benefits of this new cinematic season. Its combination of old-fashioned romantic swashbuckling and new computer-driven camera effects proved irresistible to older and younger audiences alike, while its innate gentleness was acceptable to mainstream audiences of both genders. George Lucas had produced a futuristic film steeped in not-so-subtle nostalgia – for Hollywood adventure, for science fiction’s expansiveness, and for a future reassuringly set ‘a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away’. The film’s success, along with that of Steven Spielberg’s gargantuan, sentimental Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), established the centrality of science fiction as a Hollywood genre. Technically innovative but ultimately (very) reassuring and familiar, these were canny blends. (The combination of narrative conservatism and technical wizardry had predecessors at other points in Hollywood history, most evidently at the Disney studio in the late 1930s and early 1940s.) Budgets for science fiction films were increased accordingly.

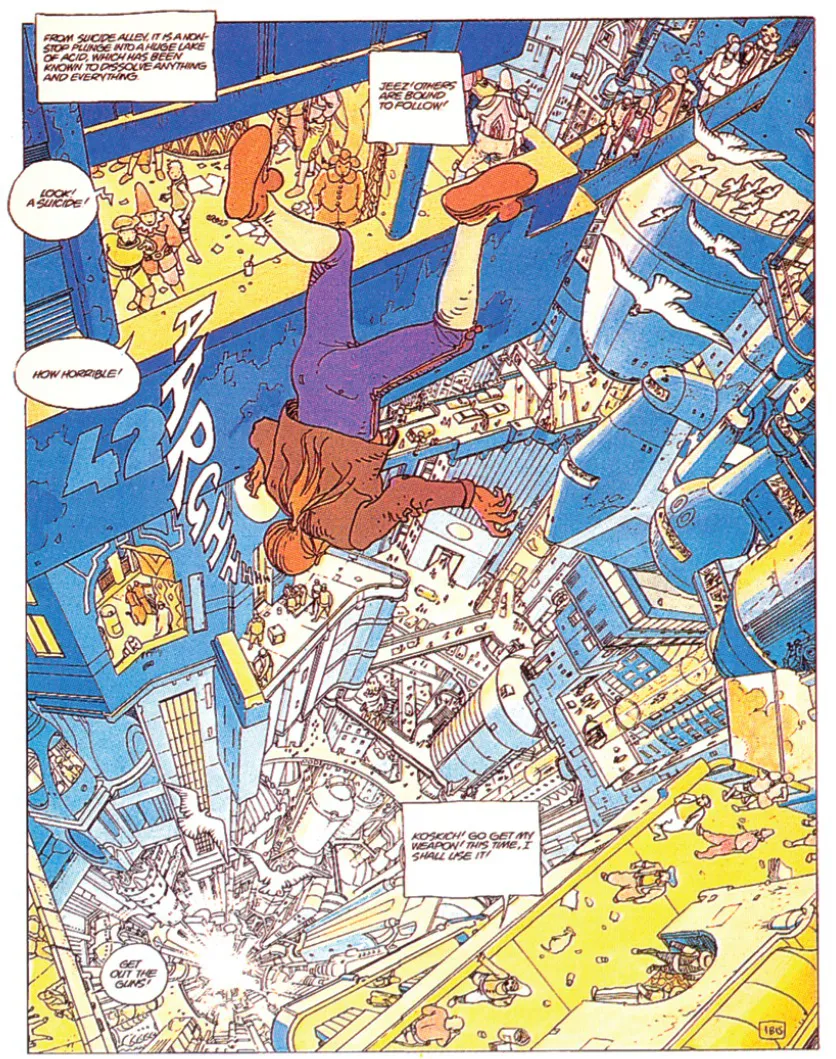

Blade Runner was to be produced through a small company, Filmways Pictures, at a fairly limited budget of $13 million. But before principal photography could begin, the script needed to be reworked. Repeatedly. Fancher ultimately produced eight separate drafts, closely supervised by the director. Scott told him to begin thinking about what lay outside the windows; about what constituted the world of the film. When Fancher admitted that he hadn’t yet considered these elements, Scott told him to look at Metal Hurlant, a rather lavishly produced French comics magazine (published in English as Heavy Metal) that had attracted some of the form’s most innovative creators. Heavy Metal artists produced visually dense science fiction fantasies with baroque designs, airbrushed colour and elaborate linework, as well as highly exaggerated scenes of violence and sex. The aesthetic of Blade Runner derives heavily from a number of these creators: Moebius’s compacted urbanism, Philippe Druillet’s saturated darkness and Angus McKie’s scalar exaggerations come easily to mind.

Disagreements between Fancher and Scott were multiplying, however. While Scott continued to elaborate on the atmospheric world outside the windows, he was also winnowing down the complexity of the story, and Fancher was resisting. With the start of shooting only two months away another writer, David Peoples, was hired to complete the script. Peoples was an editor and aspiring screenwriter: he had edited the Oscar-winning 1977 documentary Who Are the Debolts? (And Where Did They Get 19 Kids?), co-written and co-edited The Day After Trinity in 1980, and would later script Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992). Peoples said that ‘Ridley was sort of heading toward the spirit of Chinatown. Something more mysterious and foreboding and threatening.’14 The actual shooting script was an amalgam of Fancher’s work, Peoples’s December 1980 rewrite and a later partial rewrite by Fancher. Peoples has been credited with tightening the mystery aspects of the screenplay and deepening the humanity of the android adversaries, now known as replicants.

The headlong imaginings of Moebius in Heavy Metal

Scott, revealing an awareness of the textures of science fiction, had been toying with the role of language in his strange new world. He wanted to find new names for the protagonist’s profession as well as his targets – detective, bounty hunter and androids were overly familiar terms, no longer evocative enough. Fancher, rummaging through his library, found William Burroughs’s Blade Runner: A Movie, which was a reworking of an Alan E. Nourse novel about smugglers of medical supplies (‘blade runner’ also sounds a lot like ‘bounty hunter’, Deckard’s profession in the novel). The rights to the title were purchased from Burroughs and Nourse. ‘Replicant’ was the contribution of Peoples, whose microbiologist daughter suggested some variation on ‘replication’. The substitution of unexplained terms such as ‘blade runner’ and ‘replicant’ for more familiar ones was typical of Scott’s approach, which was rooted in an intriguing combination of the specific and the suggestive.

As the script was being finalised in December 1980, Filmways balked at the expense and withdrew from the project. Over the next two weeks, Michael Deeley managed to put together a new financing arrangement. There would be three participants, providing an initial total budget of $21.5 million (later raised to $28 million – up considerably from the original $13 million estimate). The Ladd Company put up $7.5 million through Warner Bros., which was granted the domestic distribution rights for the film; Sir Run Run Shaw put up the same amount in exchange for the foreign rights; and Tandem Productions, a company run by Norman Lear, Bud Yorkin and Jerry Perechino, put up the remaining $7 million for the ancillary rights (television, video, etc.). Tandem also served as completion bond guarantors for Blade Runner, which gave them the right to take over the picture if it went over budget by 10 per cent.15

The Look of the Future

Alien must have been tremendously valuable preparation for Blade Runner. While its story was filled with horror film clichés that existed uncomfortably within the high-technology spaceship settings, the design of the film raised it to another level of importance. Scott divided the design responsibilities, so that H.R. Giger, for example, was only responsible for the design of the alien beings and artifacts. Meanwhile, the spaceship-tugboat Nostromo, with a vast ore-processing factory in tow, was a masterpiece of corridors and cluttered lived-in spaces, and Scott’s hand-held cameras and use of available light gave the film an almost documentary-like authority. The design and casting of Alien raised issues pertaining to race, class and gender, most of which were only briefly suggested by the film’s script. The environment of the film became its most potent site of meaning, even before the appearance of Giger’s stunningly complex alien creature. Alongside the film’s unlikely narrative events, Scott succeeded in creating a masterfully plausible and nuanced space.

The spaceship as factory, drifting in the voids of interstellar space, recalls the Pequod of Moby Dick, which in Melvill...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: On Seeing, Science Fiction and Cities

- 1. Filming Blade Runner

- 2. The Metropolis

- 3. Replicants and Mental Life

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Blade Runner by Scott Bukatman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.