![]()

FILM ANALYSIS

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Now the Queen of Carthage/ will accept suffering as she accepted favor:/to be noticed by the Fates/is some distinction after all./ Or should one say, to have honored hunger,/ since the Fates go by that name also.

Louise Gluck, ‘The Queen of Carthage’

Credit Sequence

Bonnie and Clyde opens with thirty-two sepia tinted photographs interspersed with black and white credits. Accompanying the visuals throughout the credit sequence is the clicking of a camera shutter and, from the point when the picture’s title (after the sixteenth photograph) appears onward, the sound of Rudy Vallee singing the romantic love song, ‘Deep Night’ growing gradually louder. The first fourteen photographs contain an assortment of period portraits of Depression era farm families, much in the style of Walker Evans. We see various shots of parents (and a few grandparents) and their children in different group poses, of ramshackle farmhouses and desiccated fields, and of kids wearing bib overalls and playing on farm vehicles. As the white credits naming the performers and the title appear on the otherwise dark screen, they slowly dissolve to red and then fade into the black background, a grim foreshadowing of the blood and death to come.

Approximately halfway through this series of photographs, the still images shift from family portraits to shots of the historical Bonnie, Clyde and their gang members. At first, these figures seem as innocuous as the farm families, including a jocular picture of three men eating watermelon and another of a young woman posed pensively on a hillside. A violent element soon emerges, however, and then comes to dominate this progression of scenes: in photograph twenty-one, a trio of men stand in front of a shack with their weapons; in twenty-eight, two men lean on the hood of a car cradling rifles; in number thirty, three kneeling men fire their guns down the road at an unidentified object. Finally, the last two photographs juxtapose text with images. Vertical pictures of Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty on screen right are accompanied by short biographies of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow on screen left.

This short credit sequence beautifully contextualises both the film’s characters and its plot. By starting with actual period photographs, Penn firmly situates the film within a particular historical era and simultaneously establishes a beguiling sense of accuracy and credibility for his fictional characters and their actions. In addition, the sequence subtly introduces thematic and visual motifs that Penn interweaves throughout the rest of the movie, including the creation of families, the escalation of violence, the connection between parents and their children, the desperation of the times and the poverty of rural life. Even more importantly, he introduces the concept of visually documenting these moments, of freezing a moment in time and, thereby, preserving it forever. And, of course, he initiates the act of taking staged pictures which plays a significant role throughout the movie.

‘The Things That Turn Up In the Street These Days’: The Meeting of Bonnie and Clyde

Following the credit sequence, the film begins with an unusual visual moment: an extreme close-up of an unknown woman’s lips as she applies lipstick and then licks them to add tantalising moisture. This disorienting image plunges the audience directly into the action, without the comfort of a traditional establishing shot, thus denying the viewer any knowledge of physical place or character identification. (It may also be a sly visual allusion to the famous shot of Orson Welles’ lips in Citizen Kane; that Bonnie’s mouth is shaped into what is generally called ‘rosebud lips’ adds to this possibility.) When the woman rises, we see she is naked, save for a pair of skimpy panties. Penn’s next series of shots clearly expresses this woman’s frustration without a single word. She flops down on the bed, hits the bars and then pounds on them; her face rises until it rests, imprisoned, between the bars and ends with a close-up of her entrapped eyes that provides ample evidence of her crippled mental state.

From here, Penn cuts outside the tacky bedroom and his high-angle shot shows a dapper young man casing a car outside the woman’s home. When she calls out ‘Hey Boy’, he turns to find a naked woman, totally unashamed of her nudity, filling the frame of an upstairs window. Telling him to wait, she hurriedly slips on a flimsy dress and bolts down the rickety stairs. Penn situates his camera at the bottom of the staircase, so that when she dashes out of the house, we watch from a low angle, as if peering up her dress. Arriving breathlessly outside and still buttoning up her dress, the woman is somewhat surprised to find him still waiting for her.

The film’s disorienting opening image

At the invitation of the young man, the couple stroll into town to buy a Coke, and the camera tracks along with them. The man reveals he was in state prison and even chopped off two toes to avoid a work detail. Ironically, he was paroled the next day, so his sacrifice represents the first darkly comic moment in the picture. Even though this is Main Street, it is almost totally deserted, filled with abandoned buildings, empty stores and boarded-up businesses – including a closed movie theatre. Again, Penn shows the woman trapped within the frame. As she circles the soda bottle invitingly with her lips, she is pinioned between the man swigging his Coke – an unlighted match bouncing up and down on one side of his mouth – and the gasoline pump of a vacant gas station. ‘What’s it like?’ she asks of the armed robbery that got him a stretch in prison. ‘It ain’t like anything,’ he replies.

This short verbal banter, like so much of the seemingly casual dialogue in this first sequence, provides valuable clues to each figure’s character that will be developed and elaborated as the film progresses. The intellectually curious woman wants specific information about how things feel, particularly those actions which promise excitement and the possibility to break out of her boring life. She appears emotionally inquisitive and intellectually capable of delving beneath appearances to deeper concerns. The man, however, lacks her capacity for thinking beyond the surface of events; he answers her open-ended question with the most mundane, amorphous and, ultimately, useless information about these sensations. Throughout the film, this pattern emerges over and over again. The innately perceptive Bonnie struggles to express the significant implications and emotional toll their activities exact on their relationship, while the basically inarticulate Clyde rarely raises his consciousness beyond planning the physical details of their life together. In fact, in the first crime committed after they meet, it is Bonnie who challenges Clyde with not having the ‘gumption’ to use the gun, daring him to rob Ritters corner grocery store.

Following the grocery store hold-up, they steal a car and, accompanied by Flatt and Scrugg’s bluegrass rendition of ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’, make their getaway, after finally introducing themselves to each other and the audience. Careening from side to side down a dusty road in their stolen vehicle, an obviously stimulated Bonnie excitedly hugs and kisses Clyde as he steers around oncoming vehicles and struggles to keep the car on the road. Finally, he parks in a deserted patch of green, first cajoling her ‘to slow down’ and ‘take it easy’, then thrusting her aside and demanding that she ‘cut it out’, and finally bolting from the car and limping away into the field. ‘I ain’t much of a lover boy,’ he tells her. ‘I never saw the percentage in it.’ ‘Ain’t nothing wrong with me’ he quickly adds with a goofy grin, followed by ‘I don’t like boys or anything’ as he tries to extract his head through the window and comically bangs it on the car roof. The flustered Bonnie, lighting her cigarette, can only muster the observation that ‘Your advertising is just dandy. Folks just never guess you didn’t have a thing to sell.’

This sequence releases the suppressed sexuality which has oozed, barely contained, just beneath the surface from the film’s opening moments. Bonnie’s enticing nakedness in her bedroom, Clyde’s bouncing phallic toothpick, Bonnie’s seductive soda drinking and her salacious caress of Clyde’s strategically placed pistol, her mauling of Clyde as he drives the getaway car, all charge the film with a pervasive eroticism which seems destined to culminate in sexual intercourse immediately following the hold-up. But it doesn’t. Instead, Clyde, in one of his few effective rhetorical flourishes, mesmerises Bonnie with his plans for them, capturing her with a picture of wealth and fame that makes the satisfaction of mere animal appetites pall in comparison to the world they will inhabit as glamorous criminals. What Clyde offers Bonnie stretches far beyond the physical gratification he is incapable of providing her. His captivating vision of how she can escape her drab surroundings, of who she could become and of what she deserves in this life transcend his physical failure, though his impotence will create ripples of discontent and disappointment for the rest of the picture.

Penn now cuts to a greasy, nondescript diner where Clyde tells Bonnie the story of her dreary existence as a waitress. He correctly surmises how every day she returns home from the dingy restaurant she hates, stares into the mirror and desperately wonders, ‘When and how am I ever gonna get away from this?’ At this point, Penn incorporates one of the subtle, soundless moments of realisation that fill this movie. An older waitress, sporting garish red hair and witlessly snapping her gum, brings the couple their food. Noticing the spit curl hugging her ear, a parallel style to Bonnie’s hairdo, Clyde authoritatively tells his new partner, ‘I don’t like that. Change it.’ She obediently complies. The figure of the older waitress contains the potential future of Bonnie Parker if she refuses to alter her fate. Her life will consist of greasy food and dumb truck drivers, a joyless existence that will extinguish all the sparks of creativity and intelligence she clearly possesses. Given this fleshy prophecy, we immediately understand why Bonnie opts for crime over tedium, no matter what the consequences. They exit the restaurant, steal another car and head down the road.

‘We Rob Banks’: On the Road with Bonnie and Clyde

This short sequence extends some of the ideas expressed in the early scenes and establishes a visual construction that dominates the film and, in fact, has already appeared in previous scenes: windows and mirrors. While he claims that he sleeps outside to stand guard, Clyde clearly hesitates to put himself in a situation that might suggest the possibility of physical intimacy. His sexual hesitancy, however, is replaced by a swaggering bravado when he talks about his prowess with a weapon. For Clyde, this expertise and marksmanship compensates for his lack of sexual potency. One could even view the escalating violence that ensues as his most powerful means of establishing a sense of traditional manhood and his most effective strategy for keeping Bonnie by his side. The breaking of glass comes to represent the fragile boundary between the inside and the outside worlds inhabited by the Barrow gang as opposed to their enemies and fans. Earlier, we saw Bonnie’s fascination with her own visage in the bedroom mirror, and this preoccupation with style and image will grow as the film evolves. At this point, however, both images are underplayed and seem more naturalistic than expressionistic.

Bonnie’s natural talent for gunplay

Finally, there is Clyde’s braggadocio introduction of their occupation: ‘We rob banks.’ Of course, they have not yet robbed a bank, and their initial attempt in the next segment will be a conspicuously comic failure. It is more important to note that Clyde spontaneously identifies with the dispossessed homeowners forced by the banks to relinquish their property, pack up their families, cram their belongings into dilapidated trucks and set out in search of a place to make a living. Throughout the film, Clyde and his gang make clear distinctions between people and institutions. The latter represent a faceless, heartless expression of governmental ineptitude and failure, the former the human face of this political tragedy. Thus, their bank robberies represent more than simple greed or even economic desperation; they symbolise a frontal attack on the cruel policies that have humiliated the people and destroyed the backbone of rural America’s social and economic organisation.

‘There Ain’t No Money Here’: The Farmers State Bank Robbery

Penn constructs this first foray into bank robbery along decidedly comic lines, but the responses of the characters reveal much about their personalities. Clyde is jumpy and jittery, obviously nervous. Penn undercuts his natty outfit by inserting an errant collar point that sticks straight out, giving him the appearance of a freshly scrubbed little boy self-consciously awkward in his best Sunday outfit. Bonnie, on the other hand, has exchanged the flimsy, sexually suggestive beige dress with the plunging V-neck collar she wore in the first scenes for a far more sophisticated ensemble: stylish, high-neck grey sweater, jaunty midnight blue beret and matching blue scarf with grey lines and patterns. With her perfectly coiffed hair and flawless make-up, she is clearly dressing for success in her new profession. (Where she found these clothes in backwater Texas remains a mystery.)

Besides the obvious social commentary concerning the failed bank which ‘guarantees’ its customers fiscal security, two elements in this short sequence remain important: the characters’ response to the miscalculation and Penn’s continuation of the glass imagery. By dragging the teller out to Bonnie waiting in the car, Clyde demonstrates that impressing her remains his foremost objective. Whether by spinning dreams, robbing banks or shooting guns, Clyde continually strives to compensate for his lack of sexual prowess, here forcing the bank clerk to absolve him of responsibility for this mistake. Bonnie, with her greater sense of the absurd and deeper personal perspective, immediately grasps the irony of the situation, while Clyde remains fixated on more concrete concerns: their financial condition.

The most interesting visual moment in this sequence occurs as Clyde hauls out the clerk to explain the mishap to Bonnie. Penn keeps the audience inside the bank looking through the window at what is going on outside, again framing an essentially silent scene. He never allows us to hear the explanation and forces us to view the interaction played on a screen limited by the parameters of the bank window. So, in effect, he stages a silent film moment within a contemporary talking film: we watch the action through two distinct screens, one inside the theatre and one inside the frame’s action. And, of course, Clyde’s destruction of the bank window, with its fraudulent claims of fiscal stability and capital ($70,000), essentially breaks the transparent wall that had earlier been established between actors and audience. He literally shatters the theatrical illusion, simultaneously exploding the artistic construct (the screen within a screen) and the social deception (financial protection).

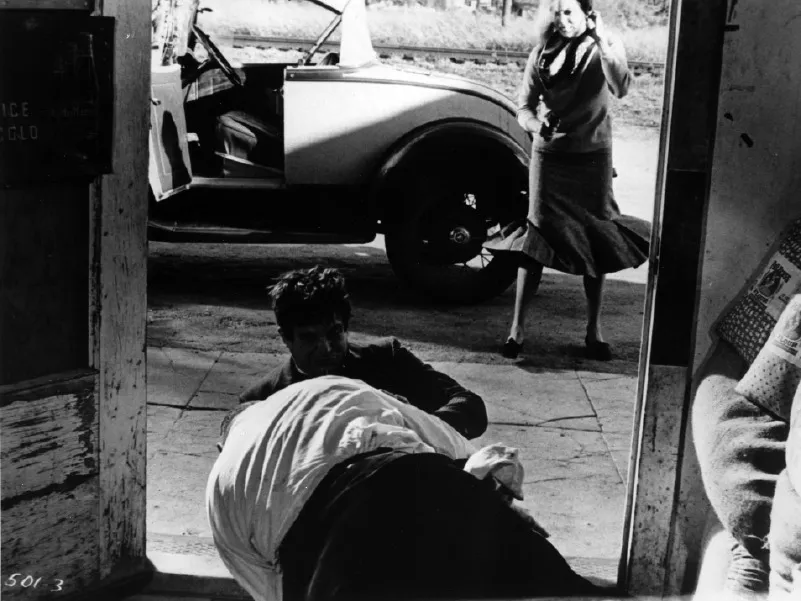

Violence in the film steadily escalates until the final explosion of bullets

‘I Ain’t Against Him’: The Grocery Store Robbery

This brief scene initiates the slow escalation of violence in the film. In Clyde’s earlier hold-up of Ritters grocery, as well as his firing bullets into the windows of the abandoned farmhouse and the failed Farmers Bank, no one was hurt. Here, however, there is a victim, though no one is killed – yet. During the robbery, Clyde fails to understand that he is stealing from the same type of people with whom he claimed allegiance earlier, those blue-collar workers desperately trying to eke out a meagre living and avoid bank foreclosure on their property. His boyish grin as he nonchalantly waves the gun and presses the store clerk for peach pie presents his disingenuous illusion of himself as a dutiful husband out shopping for the wife and kids at the corner store. So it totally shocks him when the butcher attempts to chop off his hand and refuses to let him leave the st...