eBook - ePub

Bombay

About this book

A Landmark in recent Indian cinema, by acclaimed director Mani Ratnam. In January 1993 sectarian rioting left 2,000 Hindus and Muslims dead in Bombay. Only two years later Mani Ratnam's audacious Tamil film Bombay (1995) used these events as a backdrop to a love story between a Hindu boy and a Muslim girl. Bombay was condemned by Muslim critics for misrepresentation and it was embroiled in censorship controversies. These served only to heighten interest and the film ran to packed houses in India and abroad. Lalitha Gopolan shows how Bombay struggles to find a narrative that can reconcile communal differences. She looks in detail at the way official censors tried to change the film under the influence of powerful figures in both the Muslim and the Hindu communities. In going on to analyse the aesthetics of Bombay, she shows how themes of social and gender difference are rendered through performance, choreography, song and cinematography. This is a fascinating account of a landmark in recent Indian cinema.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Production, Censorship and Reception

Toward the end of 1993, Ratnam went to Bombay to learn firsthand the magnitude of the riots. The trip included long conversations with Padamsee, who played an active role in the formation of Citizens for Peace, a spontaneous response to the riots; Asghar Ali Engineer, who has devoted many years to keeping alive the idea of a secular India; as well as other community leaders from the English-speaking sections of Bombay, whose secular aspirations have been betrayed, and, in effect, propelled several of them to initiate various peace-keeping efforts.

Ratnam also visited Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum and the setting of Nayakan, to meet the poorest and hardest-hit victims of the riots. Listening to the victims’ accounts, it was slowly becoming clear to him that there was no consistent story about the rampant violence. Several of them had not only suffered aggression but also had not hesitated to retaliate. In a small way, the inability of the victims either to take full responsibility or categorically blame a certain segment of society surfaces as a predicament in the film. In the final reckoning, the film remains a liberal response to the Bombay riots, blaming both Hindus and Muslims equally without ever recognising the societal inequalities that mark Hindus as the dominant population group and Muslims as the beleaguered and economically disadvantaged minority.

Although Ratnam encountered a cross-section of Bombay on this trip, he did not meet with members of the Shiv Sena, which had unabashedly admitted targeting Muslims. The party’s interests in the film would adversely affect its release, but that story will have to wait to be told.

Several of his encounters and stories from this trip obtained in the film: Dileep Padgaonkar, the journalist who had persevered in providing the detailed accounts of the riots that eventually emerged as the founding document for civil rights activists and the courts, was undoubtedly a thinly disguised model for the character Shekhar; and a police officer who had shown impartiality with the marauding mobs and had not been afraid to prevent them from committing further acts of violence became the model for the harried officer who tries to defend his position when interrogated by Shekhar after the first blast.

Besides trying to document stories, Ratnam was piecing together the visual look of the city in the aftermath of the riots. In keeping with this idea, the yellow hues that had evoked the 1950s in Nayakan were replaced by the colour palate that he conceived for Bombay: serene blues to open the film in southern India, vibrant reds for the volatile Bombay cityscape, black for the riot-infested parts of the narrative, and a slow change from black to blue as reconciliation takes place. In addition to composing the colour scheme, Ratnam also borrowed from the vivid, yet melancholic, images of news photography: the abandoned car, the twisted metal, the gutted buildings and the forgotten corpses, whose images appeared on the covers of national newspapers and were subsequently collected in Padgaonkar’s book.8 While news photographs served as a primary source for the visualisation of violence, Ratnam was also aware of the documentary films that had sprung from these events and recorded with great vigilance the violent events of December 1992 to March 1993. Among the films that confronted hostile mobs, who had little compunction about destroying film equipment or attacking the photographer, Ratnam was drawn to Suma Josson’s Bombay’s Blood Yatra (1993) as emblematic of the on-the-ground reporting of the riots.

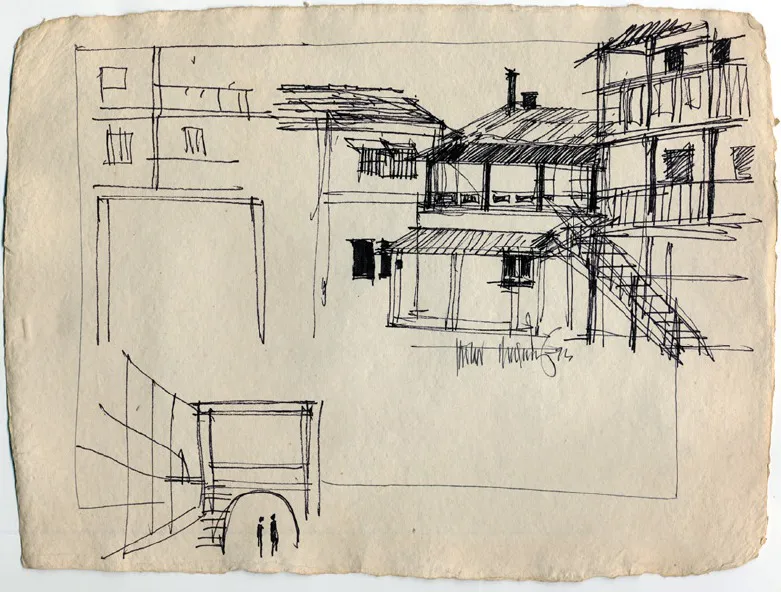

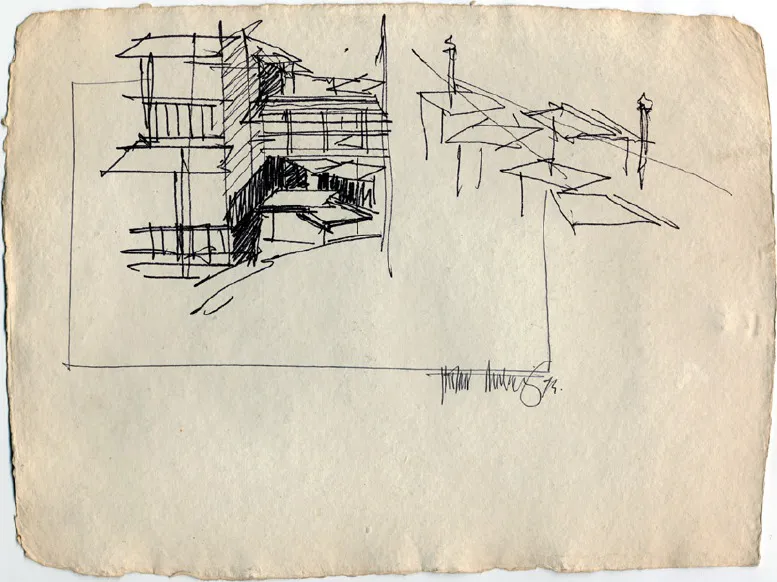

Armed with details, both visual and narrative, Ratnam returned to Madras to start production. Although the film was about Bombay, Ratnam constructed his set in Madras, where he could exercise greater control; at the end of shooting, he had spent only three or four days in Bombay. Once again, he called on his art director, Thotta Tharani, who had helped create the Bombay cityscape for Nayakan, to erect a set on an empty lot of the Campa Cola estates in Guindy. For 30 lakhs of rupees, Tharani produced extensive sketches of a Bombay neighbourhood, with shops squeezed next to each other, apartment dwellings standing cheek by jowl, layers of clothes hanging out to dry from every window and balcony, and a frenzied collection of billboards. It is to this Bombay that Shekhar wants to escape from his bucolic village, and it is this Bombay that welcomes Shaila. Although the set Tharani constructs for Bombay is not the large slum that we see in Nayakan, it is still close to the red-light district, an economically precarious neighbourhood inhabited by sex workers, immigrants from the south and Hindu fundamentalists – a ragbag of characters who surround Shaila and Shekhar’s home.

Sketches of the set for Bombay by art director Thotta Tharani

While the sprawling grounds of the Campa Cola factory were ideally suited for the street and neighbourhood scenes, Ratnam chose an abandoned building in the Express Estates, also in Madras, for the interior shots of Shekhar and Shaila’s apartment (when the building was torn down in December 2003, obituaries recalled its role in Ratnam’s films). The Indo-Sarcenic architecture in the Express Estates, with its tall columns and high ceilings, appears in several of his films, including as Nayakan’s home and as the hospital in Alaipayuthey. In a delightful play of spatial discontinuity, Ratnam used the interiors of a house on the perimeter of Madras for the scenes in Shaila’s family home; an impressive feudal mansion in Pollachi, seen in the Tamil film Thevar Magan (1992), as Shekhar’s parents’ home; and Kasargod for the opening scenes in the fictitious village of Maanguddi, whose causeway and bridge appear once again in Alaipayuthey. Ratnam is not alone in creating a diegesis in the form of a geographical jigsaw puzzle; film-makers have long been aware that continuity in cinema need not be limited by a theatrical mise en scène; the cut can transport us from Kasargod to Pollachi without missing a beat of Shekhar’s desire.

It was logical to invite cinematographer Santosh Sivan, who had filmed Roja and seemed to exhibit a particular sensitivity, to convert topical issues into saleable commercial ventures. But Sivan was shooting Indira (1995), directed by Suhasini, Ratnam’s wife, and was unavailable for this assignment.9 However, choosing a substitute for Sivan was less than straightforward. In the search for an actor to play Shekhar, Ratnam screen-tested Rajiv Menon, a successful cinematographer who ran his own advertising firm, RM Productions, in Madras. However flattering it is to play the hero in a popular film, Menon preferred to pitch for the role of the cinematographer, a career for which he had trained at the Madras Film Institute, and he successfully managed to convince Ratnam of his intentions. Like Sivan, Menon launched his own directorial career after working with Ratnam directing Minsara Kanavu/Electric Dreams (1997) and Kandukondain Kandukondain/I have seen you (2000).

Director Mani Ratnam and cinematographer Ravij Menon on the set of Bombay

Once recruited, Menon had his own ideas for this project. He wanted his cinematography to look distinctly different from Ratnam’s longstanding and successful collaboration with P. C. Sriram, which featured backlighting and was dominated by framed doorways and the colours of dusk. Inspired by the documentation and re-creation of the Vietnam War, Menon took for his models Apocalypse Now (1979) and The Killing Fields (1984) to convey a ‘heightened sense of reality’ that was horrifying yet would be ‘stunning and beautiful’.10 Some of the images of the police action in India were also imprinted on his mind: roads littered with slippers, pools of blood on the tarmac, burning tyres, white and black smoke clogging the air. All of these images governed the visual grammar of violence in Bombay, making it, according to the well-known cinematographer, Ashok Mehta, visually one of the best films, and yet one that surprisingly failed to garner many awards.

Violent film scenes invariably create their own casualities, and Bombay racked up a few despite the special-effects technicians on board. Even before the shoot began, Menon had an accident while hunting for a location: he slipped and fell on a monsoon-drenched path in Kasargod, incurring a deep gash to his forehead. For most of the shoot, a bandage hampered his sight in one eye. More accidents followed for the crew once shooting began: Menon fell over the crane and found himself dangling from a dangerous height; in one of the riot sequences, a bayonet sliced the face of the focus puller, Gaja, who was trying to get a better shot; an actor burned his thighs while trying to smother swiftly moving flames in one of the scenes. These accidents, none of which was mentioned in reviews of the film were recounted with relish by cinematographers as survival stories and the occupational hazards of the profession.

Mani Ratnam directing Arvind Swamy in Bombay

Having lined up a cinematographer, Ratnam next turned to casting the characters. Mahima Choudhury was briefly in the running for the role of Shaila Banu, but Manisha Koirala was a stronger contender. Koirala had recently earned critical attention for her performance in Saudagar (1991), particularly from cinematographer Anil Mehta, who recommended her to Menon. She flew to Madras for a screen test, and Menon’s still photographs convinced Ratnam that Koirala was a perfect fit for Shaila Banu. For the part of Shekhar, Ratnam now looked no further than Arvind Swamy, whom he had cast in Roja. The hunt for the twin boys was resolved in Hyderabad, where the two young actors had appeared in a couple of commercials. Unlike the vast number of children who have appeared in Ratnam’s films, this pair of twins did not care for acting and reportedly spent most of their time during the shoot revelling in the successes of their favourite Indian cricketers Sachin Tendulkar and Vinod Kambli. One of the boys was more receptive to direction, and Ratnam did not hesitate in using him as a body double for his brother in the more emotionally challenging scenes. Several members of the supporting cast were recruited from Ratnam’s stable of regular actors – among them Krishnamurthy, or Kitty, who appeared in Agni Nakshtram and Nasser and Tinnu Anand, who acted in Nayakan. Others, like Prakash Raj, would appear again in Iruvar.

Although Ratnam’s storytelling style is heavily linear, his shooting process is more scrambled, straightened out later in the editing room. For instance, the shooting of Bombay began in 1994 with scenes in the couple’s flat in Bombay followed by scenes of rioting. The film crew then headed to Kasargod in Kerala during the monsoons in June and July to shoot the opening sections of the film, to Bekal Fort for the song ‘Uyire’, and to Madurai to shoot the wedding song at the Tirumala Nayak palace. A short trip to Bombay with a small crew yielded a few images for the ‘Hula Bula’ song as well as the establishing shots that punctuate the film. The shooting ended in Ooty with the ‘Kuchi Kuchi Rakamma’ song. In seven or eight months, Ratnam averaged a shooting ratio of 1:5 film footage, which he regularly edited between shoots, allowing him to have a print ready for release in Tamil, Telugu and Hindi in December 1994. But a series of events involving the Board of Censors in Madras and Bombay, protests from communal groups and instructions from the police delayed the film’s release until April 1995.

Roja’s success ensured advance publicity for Bombay, although some of it was unsolicited. Manisha Koirala had allegedly revealed bits of the plot to a reporter, ignoring Ratnam’s wish to keep it secret. Of course, in reprimanding the actress for compromising the film’s release, Ratnam sparked even more talk. And then there is the notorious story involving the Shiv Sena chief, Bal Thackeray, who had go...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Production, Censorship and Reception

- 2. Genre and Style

- 3. Final Images

- Appendix

- Notes

- Credits

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Bombay by Lalitha Gopalan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.