- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Belle de Jour

About this book

Severine (Catherine Deneuve) is a listless haute bourgeouise wife with a secret afternoon life of prostitution. Her life twists repression and guilt together with uninhibited behaviour, strangled libido with its liberated counterpart. Luis Bunuel was catapulted into cinematic history by his groundbreaking Dali collaboration, Un Chien Andalou, in 1929, but it is Belle de Jour (1967) which inaugurates the extraordinary late phase of his work. It is a film shimmering with reflections on truth, fiction and fantasy, in addition to caustic social insight, as it tells the story of a woman clearing her mind, perhaps, of its ghosts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STYLES OF IMPATIENCE

Buñuel liked to insist that he had no film style, or that the best styles are invisible. These are two not entirely compatible claims, but they point in a single direction: style is not to be detachable, a distraction. Starting from his silent Surrealist films and working through his Mexican works Buñuel converted a mixture of invention and indulged ineptness – too much skill or familiarity with film grammar would be close to capitulation to the mainstream – into a fully intentional ragged poise, a careful flouting of rules of composition and sequence. In their later years he and Gabriel Figueroa, director of photography on Los Olvidados, El, Nazarín (1958), La Fièvre monte à El Pao (1959), The Young One (1960) and The Exterminating Angel, would make jokes and tell stories about their old differences. Roughly, Figueroa knew how to get a wonderful, haunting, harmonious look on the screen, and Buñuel took that as the measure of what he didn’t want – a standard of beauty he could turn into awkwardness. Of course he also left many of the frames to Figueroa’s taste, or made his films out of a combination of their two tastes, so the final result isn’t all awkward – just liable to tip into awkwardness when least expected.

In spite of his claims, then, Buñuel’s film style is visible to anyone who cares to look, best defined perhaps as a form of impatience, a refusal to wait around for glamour or contemplation. It’s the impatience which makes the slow moments stand out – like the shot of the little girl leaving a plague-stricken house in Nazarín, trailing a long sheet behind her. Buñuel is not going to linger on his story or his images, but a whole epidemic is in this picture of a bereft, crying child, and Buñuel knows he needs to stay with this shot, and allow its beauty to confirm its desolation. Conversely, moments like this remind us how brusque and even brutal the rest of the visual action is.

Buñuel’s discreet efficiency in this respect is more persistent than his occasional filmic gags – the egg thrown at the lens in Los Olvidados, the two marginally different takes of the same scene in The Exterminating Angel – but not less disconcerting. The effect not only converts a supposed absence of style into a style that is instantly recognisable, it makes the world on the screen look curiously optional and unstable, however realistically it is set up. Buñuel, the most careful of movie-makers, creates a discreet impression of carelessness not by the speed of his shooting schedule – which is always cited but was not unusual for commercial directors in Mexico or the United States at the time – but by the speed with which he arrives at and leaves whatever scene he is showing. Look at this, the camera says, but look quickly, because it will be gone in a moment. There is nothing here like the exploratory pace of say Visconti, or even Welles or Fellini. What is often thought to be coldness in Buñuel is also an aspect of this speed. He rarely stays long enough with anything to look as if he cares. His care is of another order.

The child and the plague in Nazarín

Belle de Jour was not Buñuel’s first colour film, but it was his farewell to black-and-white. The director of photography was Sacha Vierny, probably best known for his work with Alain Resnais (Night and Fog, 1955, Hiroshima mon amour, 1959, Last Year at Marienbad, 1961), who has also, more recently, done films for Peter Greenaway (from A Zed and Two Noughts, 1985, to Prospero’s Books, 1991). Vierny didn’t work with Buñuel again, and I don’t think we can we make a big interpretative deal out of the conjunction of the three just-named directors – except perhaps to wonder why we think of Resnais and Greenaway as stylists while we see Buñuel as something like the reverse. Vierny, I would suggest, introduces or allows into Buñuel’s work an idea of visual style which would otherwise be quite alien to it, and which becomes part of his signature.

The impatience doesn’t change, or the speed. But the raggedness, the programmatic awkwardness goes. Is Buñuel now less afraid of beauty? He understands, as I shall suggest later, that beauty may contain its own satire, but only, I would guess he thinks, in colour. Beauty in black-and-white often edges towards starkness, austerity. It can become static, but is not likely to become comic. Beauty in colour easily slides towards the calendar or the coffee-table book, towards tones of mush and self-parody – think of a film like De Sica’s Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970). Just the context Buñuel now wants to flirt with, although not exactly to enter. More precisely, Buñuel gets the straight looks of a beautifully photographed world to do a lot of the work that awkwardness used to do for him.

Séverine’s Paris

All the old narrative economy remains. No sooner does a person mention an address in Belle de Jour than we are looking at the street that’s just been named. When a character needs to find out where someone lives we simply see his friend starting to tail the person in question: no following of the following, the character just shows up in the right place, duly instructed between the frames. The Duke in this film, meeting the heroine in an open-air cafe, says he ’ll give her a lift to his château one day. The camera pans to the right across his horse-drawn carriage and up towards the coachmen, as if mildly pointing to the means of transport, and there’s a sudden cut to a shot of the same carriage seen from a quite different angle, coming from the left. The heroine is sitting in it, on her way.

The long-held shot which opens Belle de Jour ends as the camera, after letting an old-fashioned carriage approach, go past and continue on ahead, slowly pans up a row of trees toward the sky. Another director would pause here, allow us to absorb the scenery and make sense of the implied location, particularly after the leisurely, ‘aesthetic’ timing of the rest of the shot. Buñuel cuts before the tree tops are in view, shows us the carriage coming straight towards us in long shot, and cuts sharply from there to a rather strained frontal close-up of the two coachmen seen from a low angle between the figures of the two jogging horses. The effect is untidy, not because the images are not beautiful, but because their beauty has been bundled up too rapidly. Buñuel won’t wait any longer than needed for the story he has to tell, and we are likely to feel, if we feel anything about it at all, that he hasn’t waited long enough. We are already identifying, perhaps without knowing it, Buñuel’s style: away of flinging a world at us, like litter, rather than laying it out, like a lawn.

The landau approaches

The camera takes to the trees

Séverine’s coachmen

Something of this effect is present even when Buñuel slows the action down, as he notoriously does in the shot of the natty black patent shoes on the staircase leading to the Paris apartment of Mme Anaïs, the place where our troubled heroine is to spend her afternoons and earn her sobriquet as Belle de Jour – the name of a variety of convolvulus, Freddy Buache tells us, although I’m not sure either Buñuel or Joseph Kessel knew that. Séverine, the heroine, has already visited Mme Anaïs and arranged to return, but she’s still uncertain about whether she can go through with her plan. The shoes are the form her uncertainty takes on film. The camera waits on the landing below Mme Anaïs’s floor. The legs and shoes of a woman come into view, climbing towards us. We see the hem of her black coat and the bottom of her black handbag swinging lightly in the top corner of the frame. Her steps get slower as she comes up the stairs, and on one step she briefly stops completely. She continues to the landing where we are, and we see her shoes, now very close to us, almost execute a full turn, swivelling neatly towards the direction they came from. Then, with an air of timid decision, they swivel back towards the next flight of stairs. All this in a single shot, which persists as the legs and shoes climb the steps beyond the landing. The next shot is a close-up of the doorbell of Mme Anaïs’s apartment. A gloved hand rings the bell.

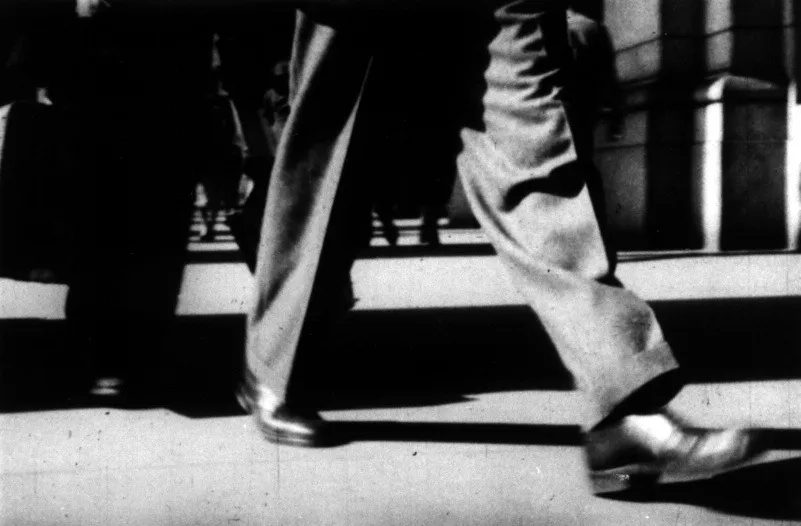

The camera is relatively patient here, but it knows where to wait, and Buñuel has of course decided on the shoes rather than any other piece of the person or her attire. By this stage – after Viridiana and Diary of a Chambermaid (1964) – shoes were an expected part of Buñuel’s signature on film, not so much a fetish as a joke. There is a delicacy in his staying away from Deneuve’s face at this difficult moment, a form of directorly tact, as if the moment were too embarrassing for snooping. But of course there also is the delightful suggestion that these neat little shoes are on their way to misbehave, that a fastidious fashion is about to get itself involved in sleaze. And indeed, a little later, when she is stripped down to bra and pants and being mauled by her first client, Séverine is still wearing the little shoes – a modern Cinderella at the brothel ball. In showing us these shoes on the stairs, as with the abandoned trees at the beginning, Buñuel is working in a kind of shorthand, leaving inferences to us, where another director, most directors perhaps, would have treated us to a considered picture of the state of Séverine’s soul. Imagine Bergman, for instance, showing us shoes instead of faces. The analogy here would be with the two pairs of shoes and legs arriving at a station in Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), boarding a carriage, and finally meeting in a compartment, where we are allowed to see the rest of Robert Walker and Farley Granger. Séverine’s approach to the brothel is more like a scene in a murder mystery than like an episode in any realistic psychology. Although of course Buñuel’s tone is different again from Hitchcock’s, even if both have a touch of comedy: doubts are not the same as suspense.

Travelling feet in Strangers on a Train

This shot also points to another crucial feature of Buñuel’s style. He ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Styles of Impatience

- 2. Production Values

- 3. Buñuel and the Novel

- 4. The Interpretation of Dreams

- 5. Séverine and the Wheelchair

- 6. Late Buñuel

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Belle de Jour by Michael Wood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.