- 127 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lawrence of Arabia

About this book

Lawrence of Arabia is widely considered one of the ten greatest films ever made - though more often by film-goers and film-makers than by critics. This monograph argues that popular wisdom is correct, and that Lean's film is a unique blend of visionary image-making, narrative power, mythopoetic charm and psychological acuteness.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lawrence of Arabia by Kevin Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Lawrence and Lawrence

I do not often confess it to people, but I am always aware that madness lies very near me, always.

TE to H. S. Ede, 3 January 19354

Titles and Names

There are incomparable splendours in store, quite soon, yet the film’s overture is simple to the point of self-effacement: a single, static overhead shot of a middle-aged man preparing to ride his motorcycle. If it were not for the grand landscape format of the image, and a luminous, almost golden glow that suffuses it, we might be watching something quite dour and drab and social-realist. The orchestral score, meanwhile, soars and strains, in a manner we would find incongruous to the point of bathos if we did not know, or could not guess, that it is less a direct accompaniment of this mundane sight than a promise of stirring matter ahead. Then the written credits corroborate what most of us already know: this movie is Lawrence of Arabia, and our motorcyclist must be Lawrence of Arabia himself.

Or is he? A pedant might say no. ‘Lawrence’ himself might have said no, angrily … As we soon discover, the character played by Peter O’Toole is about to take his fatal motorbike ride; the date must therefore be 13 May 1935, and on that day the man with the bike went by the legal name of Mr T. E. Shaw; his friends usually called him ‘TE’, and that seems to have pleased him best. … (TE died in hospital, never having regained consciousness, on 19 May.) Until very recently, before his retirement from the Royal Air Force at the age of forty-six, he had officially been A/c 1 338171 Shaw, T. E., and was a stickler for using his service number. Noël Coward made an affectionate joke about it, in a letter that began ‘Dear 338171 (May I call you 338?) …’.5

Names have weight, and the small man who bore the name ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ often did so as one might bear an uncomfortable, at times an agonising, burden. He tried everything he could to shed that name and all the myths it conjured up, including brutal renunciations of everything he cherished, from the life of the mind to bodily privacy. Spurning all attempts to make him into a grand public man, he enlisted pseudonymously in the ranks, where he tried for a while to become a complete automaton: ‘mind-suicide’ was one of his terms for this grand refusal.6 One way of telling TE’s life story would be as a kind of quest for his ‘true’ name.

His father was called Chapman – ‘Chapman of Arabia’ does not quite have the proper lilt – but adopted the family name ‘Lawrence’ when he left his wife and went to live with the woman who would bear him five illegitimate children, including Thomas Edward – ‘Ned’ or ‘Neddy’ – on 16 August 1888. (16 August, as TE liked to remember, was also Napoleon’s birthday.) TE would always sign letters to his mother as ‘Ned’ or simply ‘N’, and in his later years he seems to have toyed with the idea of resurrecting the ‘Chapman’. Had he done so, he would have been the second Chapman in English literary history to have translated Homer’s Odyssey.7

During World War I, 2nd Lt Lawrence (subsequently Captain, Major, Lt Colonel and ultimately Colonel Lawrence) became known to his Arab comrades as ‘Aurens’ or ‘Lurens’ or ‘Runs’ or more wittily as ‘Emir Dynamit’: King Dynamite. It was the American showman Lowell Thomas who created the ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ name and cult – Thomas also referred to him as the ‘White King of the Arabs’ – and when TE fled from this glamorous legend into the RAF, he became 352087 A/c 2 John Hume Ross, until an officer discovered and betrayed him. John Hume Ross remained the name on his cheque books for the rest of his life, and he used it as the nom de plume for his translation of Le Gigantesque, a novel about a redwood tree.

He took the name ‘Shaw’ in 1927 – not, he said, with any thought of his good friend George Bernard Shaw, nor his even closer friend Mrs Charlotte Shaw, the playwright’s wife, though some have doubted his denials. He served in the Tank Corps for three years as 7875698 Trooper Shaw, T. E. Thanks to his passion for Brough motorbikes, he became known to his fellow rankers as ‘Broughie’ Shaw. In his role as a writer, he used various pseudonyms, including ‘CD’ or ‘Colin Dale’ (after the underground station Colindale, the last he had used before his departure to Karachi, where he served from 1927–9). When he wanted to book a room at the Union Jack Club, he used the trusty adulterer’s standby of ‘Smith’ – 353172 A/c Smith.

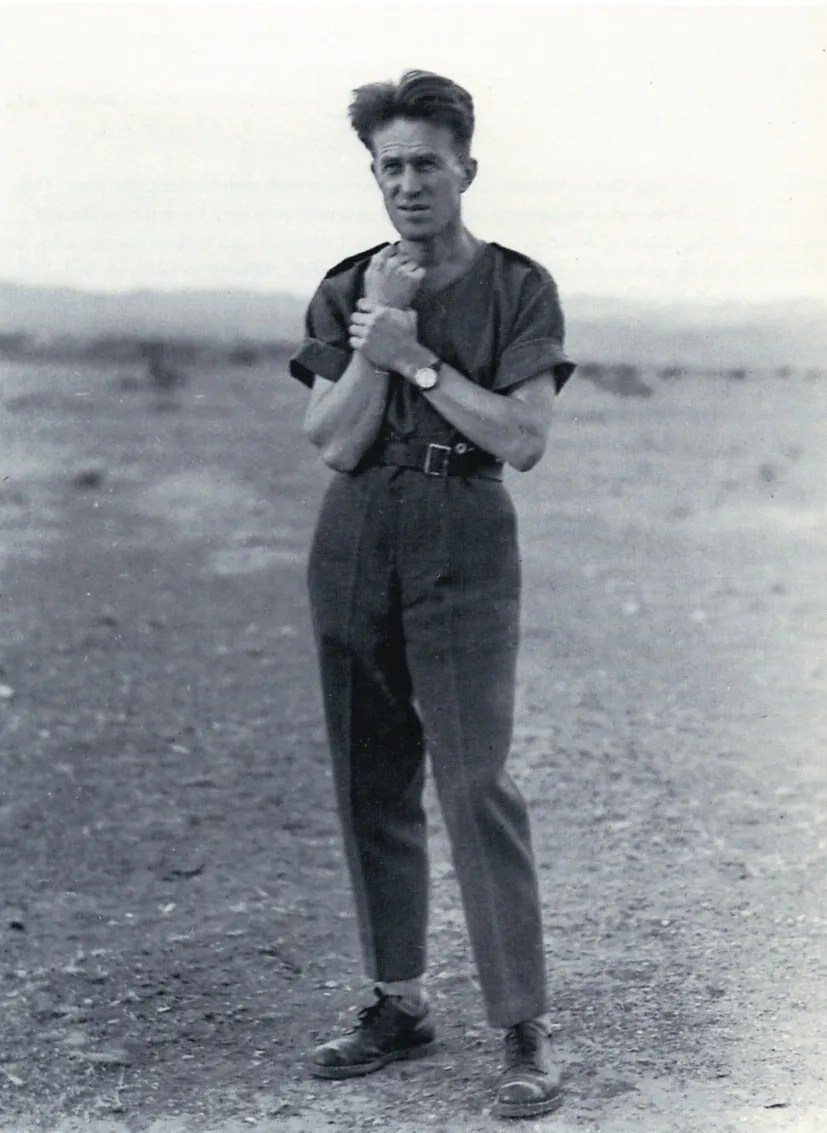

Aircraftman Shaw at RAF Miranshah, 1928

Ezra Pound addressed him, with heavy jocularity, as ‘Hadji ben Abt el Bakshish, Prince de Meque, Two-Sworded Samurai’.8 Sir Ronald Storrs called him ‘the Uncrowned King of Arabia’, and after his death the Turkish press, no friends to his reputation, called him ‘King of the Desert’ – metaphors, to be sure, but with some grounding in fact. His noble friend Prince Feisal awarded him the honorary title ‘Prince of Mecca’.

And so on. What are we to make of this? It does not require great psychological penetration to guess that a man who chafes and fidgets against the confines of a single, definitive name is likely to be complex, restless. Troubled?

Identity and Reality

Very little of that biographical information finds its way directly into the film.9 Yet the screenwriter, Robert Bolt, was well versed in the Lawrentian lore and well aware of what it implied for his task: ‘… of course the whole story of Lawrence is a man trying to find an identity for himself – Aircraftsman Shaw, Sheik this, Colonel Lawrence of the secret service.’10

Lean’s most self-consciously surreal effect – the ship in the desert

Just so: and Bolt’s screenplay for Lawrence turns again and again to the vexed question of who Lawrence might be. In this regard, one of its key scenes – a strange, trance-like sequence which owes much to pictorial surrealism11 – is the moment when Lawrence, almost at the end of his tether, finally reaches the Suez Canal after his disastrous crossing of the Sinai desert. A British serviceman calls out: ‘Who are you?’ (The line, interesting to note, was dubbed by David Lean.) Almost every sequence of the film proposes a subtly different answer to that question.

Who was he? On the positive side, Lawrence is shown as brave, stoical, visionary, tenacious, chivalric and innovative: a brilliant military strategist, a man quite free of the stupid racism of his brother officers (who cheerily call their Arab allies ‘wogs’) and of their antiquated notions of warfare; a scholar and aesthete; a superb linguist12; a compassionate man who hates injustice and sneers at pomp; a humble and exact participant observer of Arab societies who can quote the Holy Qu’ran by heart. On the negative: insubordinate, gauche, scruffy, sarcastic, narcissistic, foppish, silly, gullible, overweeningly arrogant, capricious and, in the long run, murderous – the instigator of and willing participant in an appalling massacre. Above all, Bolt’s Lawrence seethes with neuroses.

Given this intense complexity, one of the things that is truly remarkable about Bolt’s screenplay is how very tight-lipped it is on the subject of its hero’s ‘back story’ – or its ‘forward story’: all that the uninitiated viewer will know about Lawrence’s fate after Arabia is that he will ultimately die in a motorcycle accident. We learn from Lawrence’s encounter with Murray that he is ‘well educated’; from a fireside chat with his guide Tafas that he is ‘different’ from his fellow countrymen; from a similar nocturnal talk with Sherif Ali that he is the bastard son of ‘Sir Thomas Chapman’ … and that is about all.

Earlier versions of the screenplay, by other hands, had begun with Lawrence as an undergraduate at Oxford, or as an excavator on the British Museum site at Carchemish on the Euphrates. Biographies often begin with the powerful influence of TE’s mother, and the fundamentalist religious atmosphere in which he was raised. The average present-day screenwriting tutor might call Bolt’s elisions sloppy workmanship, but given the nature of its hero – initially a stranger to himself, as well as to the audience – it is entirely apt. Bolt’s Lawrence is a vivid psychological portrait, but the film has requirements greater than mere portraiture. It is epic, and tragic, not only biographical.

Epic: a sustained poetic narrative about the birth or fate of nations. Tragedy: the genre of an outstanding individual, a hero, destroyed by some fatal flaw. We do not need to know what Hamlet studied at Wittenberg; we do not need to know that Lawrence – a Hamlet forced to play the part of an Achilles – had once been a mediaeval historian, a dreamer over troubadour poetry, a connoisseur of crusader architecture and a follower of William Morris. The film is at once scathing about myth in its modern sense – the wilful fabrication of useful illusions for mass consumption – and a potent i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Lawrence and Lawrence

- 2. 1919–39

- 3. 1945–61

- 4. Shoot Part One: Jordan

- 5. Shoot Part Two: Spain, Morocco, England

- 6. Release and Reactions: 1962

- 7. Reputation and Restoration: 1962–2007

- Notes

- Credits

- Select Bibliography

- eCopyright