![]()

1

Directing the Western: Practice and Theory

The Western is one of America’s grandest inventions. Like jazz and baseball, two other unique pastimes, it represents a distillation of quintessential aspects of national character and sensibility, and has entertained millions of audiences with its intense aesthetic and ideological pleasures. Such original cultural forms and institutions testify to the American genius for the popular, expressed in a creative interplay of collective ritual and individual will, convention and invention, team play and stardom. The frontier between the personal and the social is archetypal and trans-cultural: yet is there a more American drama than of the individual performance played out within and against the checks and balances of the communal?

However, for years the freedom provided by generic narrative, the interplay of the familiar and the different, was ill-understood with reference to cinema: Hollywood movies were formulaic, empty, the enemy of art. Moreover, when French, English and American critics challenged this mid-twentieth-century mind-set, although genres achieved a measure of redemption, it was essentially as a side effect of the emergence of the director as film author. Genres provided a canvas for the creativity of the individual auteur, functioning as a pre-condition for authorship. Out of this clash of notions of dream factory versus visionaries, came the impulse to honour the tale as well as the teller that characterises my approach here.

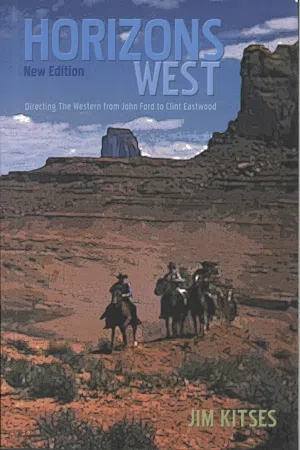

A study of the Western through the lens of its major directors, a study of its major directors within the framework of the genre: such is the dialectical premise that structures this book. John Ford and Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher and Sam Peckinpah, Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood: these film-makers can be seen as constituting a great tradition of the Western genre.

In my view this binocular approach, with an eye on both film-maker and form, is called for precisely because directing the Western as a process is hardly the simple one-way-street application of creative authority by the director that the phrase may suggest. All genres are not created equal: undemocratic as that may sound, the Western does occupy a special place within the American cinema. No other popular film form rivals it in the peak achievements and unsurpassed productivity of its artistic tradition. The genre’s unique centrality to the nation’s history and ideology has provided the fertile ground to inspire, support and shape – in a sense to direct – the careers of some of America’s most accomplished film-makers. Yet the cliché of reviewers that the distinguished film ‘transcends’ its genre provides evidence of a continuing disrespect for popular forms like the Western. In short, my aim herein is not to put forward its practitioners as the magnificent six, the heroic masters who created art out of a lowly popular formula. I come not to bury America’s greatest genre – as so many have over its long history – but to praise it as itself a creative force in the system of its authorship, a dynamic partner especially for those who have returned to the form repeatedly to accomplish their most personal work.

Will we see their like again? The Western has proved unbelievably resilient over a history that stretches back to the very dawn of cinema. Over the years the genre has frequently had its enthusiastic if premature gravediggers. In particular, many opined that a funeral was in order towards the end of the last century. From a peak of popular appeal in the 1950s, when Hollywood production of A-Westerns was at an all-time high and series like Wagon Train and Rawhide dominated American evening television, the genre had begun to decline in the 1970s, and virtually vanished in the next decade.

Once again, however, the Western confounded expectations with another renaissance, high points of which included the production of Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992). Both of these were not only commercial and critical successes but also achieved Academy Awards, a rarity for the genre. Even more impressive in some ways was the remarkable deployment of the form in two smaller, independent films: Maggie Greenwald’s The Ballad of Little Jo (1994) and Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1996). These enterprising, distinguished efforts – the first a ground-breaking Western directed by a woman, the second a revisionist vision from a film-maker closer to the experimental film than Hollywood – illuminate the greater openness and diversity that obtain in a multicultural, post-modern era.

Post-modernising the genre: Dances with Wolves

A marker in the virtual disappearance of the genre was Star Wars (1977), one of the most successful films of all time. George Lucas has been explicit in acknowledging that the Western’s absence was a prime motivating force in the creation of his series. In his eyes, the decline of the genre had created a lack, especially for the young audience, of one of the Western’s traditional forms, the morality tale. The enormous success of his efforts shows how he filled that gap with a vengeance. A generation of moviegoers emerged for whom the characters, narratives and technologies of science fiction are far more familiar than those of the Western, whose own heroes and behaviours appear quaint if not positively alien, as though from a time capsule if not from outer space. Ironically, in some families at least, an alienating divide opened up between parents who had grown up on cowboy fare and the children they dutifully squired to Lucas’s success in an altogether different generic landscape.

Yet in trying to come to grips with the apparent vanishing of America’s oldest and heretofore most enduring of genres, some critics – perhaps following Lucas’s lead – dissolved differences, suggesting that in fact the science fiction movie is indeed the Western in futurist dress. Still others have deciphered the genre beneath the disguise of the road movie: after all, what is the latter about if not the nomadic and the settled, the challenge of the unknown, the quest for America? Frequently heard, such appropriating claims suggest a need to account for a popularity that almost rivals that of the Western of old for these genres by actually perceiving them as Westerns. These arguments depend on the trick of promoting a key component of the genre – its operation as morality play, its journey structure – to the status of a defining feature of the form.

An earlier era took the reverse tack. Anxious to advance a definition of the genre that had meaningful boundaries, critics were troubled when films appeared to stretch the form, denying, for instance, that films with colonial or modern settings could be Westerns. Hewing to the notion of an ideal type naturally led critics to adopt a prescriptive stance. Most famously, the genre’s earliest and most distinguished of theorists, André Bazin and Robert Warshow, both lamented the tendency they saw in 1950s films like Shane (1953) and High Noon (1952) to justify the genre either by bringing to bear content that lay outside traditional themes or an unnecessary aestheticising.1

Those who claim that all of Eastwood’s films are essentially Westerns suggest just how far the pendulum has now swung in the opposite direction.2On the face of it outrageous, such a claim becomes understandable, given – ironically enough – an equally narrow view of the genre as essentially a vehicle for the exploration and validation of masculinity. As the great majority of Eastwood’s films work to construct or subvert a superhero male figure, ipso facto all of his films are Westerns. What such a formulation ignores is the classic structure of agreement between film and filmgoers, the institutional nature of genre that includes the audience as part of the system of production. In such a system, genre conventions function as a means both of meeting audience expectations and of organising their experience and comprehension of the film. Relevant here is an essay on the ‘nouveaux Western’ by Chris Holmlund in her Impossible Bodies: Femininity and Masculinity at the Movies. Holmlund enterprisingly groups Posse (1993), The Quick and the Dead (1995), Desperado (1995), Last Man Standing (1996), and Escape from L.A. (1996) as examples of a latter-day ‘nouveaux Western’ form. The case is principally made on the basis of the heroes, all of whom are seen as referencing Eastwood’s Man With No Name persona, and the films’ concern with machismo.3

Reading these post-modern hybrid action films as Westerns can be illuminating. Obviously, Posse and The Quick and the Dead are in fact revisionist examples of the genre, Desperado is a modern Western and the other films reference aspects of both the traditional and revisionist forms. But pace John Carpenter, Escape from L.A.’s director, who himself muddies the waters by asserting that all of his films are ‘really Westerns underneath’, the questions remain of how the dominant conventions of these various films position the audience and which genre – if any – provides the most relevant context for their reading.4

As with many post-modern films, these ‘nouveaux Westerns’ depend on a sophisticated generic fusion and interplay. Pronouncing a film like Last Man Standing a Western is useful precisely because it highlights how a generic subtext – its source in A Fistful of Dollars (1964) – informs and extends the film’s dominant noir character. This is arguably also a useful polemical strategy, a kind of generic pigeon-holing in reverse (or rather perverse). This tactic is perhaps even more extreme given the futuristic setting of Escape from L.A.. The danger, however, is of obscuring that in structure, action and iconography, it is the noir and science fiction elements that provide a set of conventions and references that shape audience understanding of these films.

But given how post-modern genre fusions hold different sets of conventions in tension and play them off against each other, trying to assert definitive identities can be problematic. Genre boundaries have always been unstable; in post-modern times they have become positively porous. At the same time, bringing to bear genre perspectives can certainly help to highlight which traditions are being drawn on, and aspects of the generic mix. Moreover, it does seem useful to make clear distinctions where we can. In the case of Posse and The Quick and the Dead, the impact of both depends directly on audience awareness of the genre’s traditional white male hero, against whom Mario Van Peebles’s African-American and Sharon Stone’s feminist protagonists are posed. Given its setting and action, it is difficult to see Desperado without an awareness of frontier mythologies: it is clearly post-modern, a pastiche Western. In contrast, it is possible for audiences to view Last Man Standing and Escape from L.A. with minimal awareness of Western referencing, and consequently little sense of that genre as a supervising source of meaning and value.

John Carpenter’s Escape from L.A.: a Western ‘underneath’?

British theorist Steve Neale has argued that Hollywood cinema has always had hybrid genres.5 While certainly true, insisting on the point in the context of post-modern examples characterised by pastiche and recycling represents a conservativism that tends to deny the feverishness and pervasiveness of current practice, as well as its often multicultural energies. The Westerns of a new millennium have clearly displayed this treatment. Thus the...