![]()

II

THE APPARATUS

![]()

5

The Frame and its Dissolution

[T]hose who acknowledge only the projected ‘movie’ as a source of their metaphysics tend to impose a value hierarchy which recognises the frame and the strip of film only as potential distractions to the flow of a ‘higher’ process, that temporal abstraction ‘the shot’.1

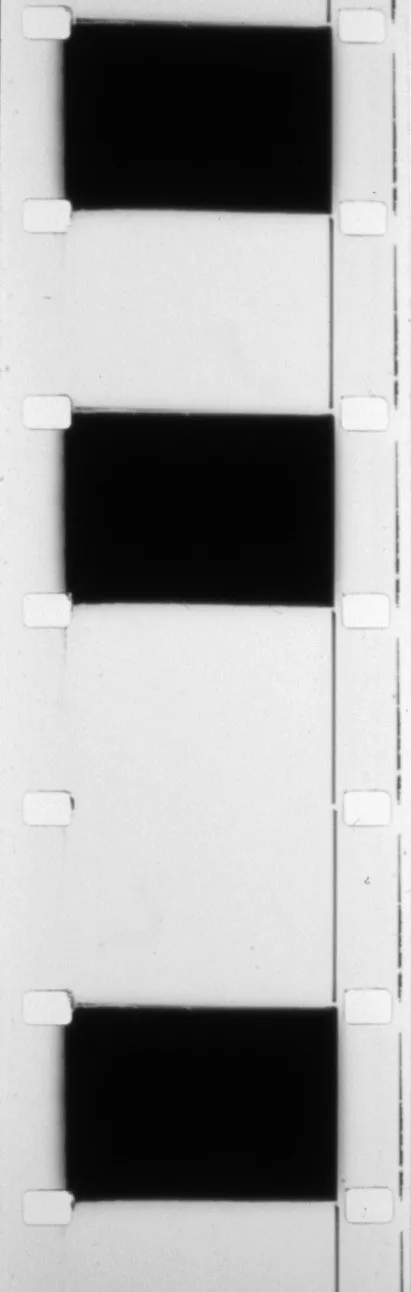

The cinematic apparatus comprises the camera, lenses, tripods and hands, the film strip and the projection event: screen, light, sound, image. It also includes the audience and their interpolation or placement within the projection event (see Chapter 4). But it is the frame, flashed twenty-four times per second onto the screen, that brings the experience to life. The illusion of movement thus generated is at the heart of the viewing experience, and this is why, for a number of film-makers, it has come to represent an obvious starting point. The frame is the fundamental unit of image, duration and rhythm. The concern with the frame also constitutes a rejection of commercial cinema’s disinterestedness in the peculiarities of the mechanisms that give rise to the image. Cinema is concerned with sustaining illusory worlds, and so any technology by which this can be achieved is all right. The frame is overlooked in favour of frames, because it is frames, and not the frame, which sustain the illusion. The discussion herein is confined to works which explore the film (as opposed to the video) frame which has notably been passed over by video artists – partly, perhaps, because the video frame is not isolatable in the way the film frame is. It does not exist in the way the film frame does, and thus cannot be treated as a fundamental unit of form like the film frame.

Film-makers as different in approach as Stan Brakhage, a lifelong sole practitioner of film, and Tony Conrad, the musician and occasional film-maker, have identified the frame as a starting point. Although irreducible, however, it is also the nexus of one of the basic dichotomies at the heart of the moving image, for the celluloid moves, but the images do not: image movement is merely an illusion in the eye of the beholder, an effect of the ‘persistence of vision’. The very technology of the camera and projector seems to embody this paradox: a feed roller winds the film through the camera at a constant speed, while the claw pulls frames intermittently into and out of the gate, where they are exposed/projected. Indeed, every pulling of a frame into the gate is simultaneously a pushing of a previous frame out of the gate, so there is a push/pull dichotomy within the constant/intermittent one.

The Flicker

One of the most prominent features of films in which the frame is taken as the basic building block of a film is the flicker effect, and Tony Conrad’s emblematic film The Flicker (1966), although not the earliest example, is a good starting point, because Conrad explicitly stakes his claim on the flicker film as a valid avenue of enquiry. After graduating in mathematics from Harvard University in 1962, Conrad moved to New York, where he worked on the soundtracks of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963) and Normal Love (1963) and Ron Rice’s Chumlum (1964), all classic films of the New York underground period. Although Conrad acknowledged the influence of Smith and Rice on his own work, he was much more influenced by the frenetic slapstick of Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le Metro (1960) than he was by the loose and laconic works of the former. His ideas about film emerge from his intensive period as a musical collaborator with the early minimalist composer/performer Lamonte Young. The concept of ‘stasis’, embodied in the long pulsating drones produced by the quartet (which included Young’s wife Marian Zazeela, and John Cale, who went on to join the Velvet Underground) finds a corollary in Conrad’s flicker films:

our music is like Indian music, droningly mono tonal, not even being built on a scale at all, but out of a single chord or cluster of more or less tonically related partials (harmonics). This does not only commute dissonance, but introduces a synchronous pulse beat.2

Conrad describes the effects of the music thus: ‘pitched pulses, palpitating beyond rhythm and cascading the cochlea with a galaxy of partials, reopen the awareness of the sine tone – the elements of combinatorial hearing’.3

The idea of palpitations beyond rhythm describes perfectly the effect of the flicker film. The Flicker ought to be rhythmical, composed as it is of sequences of regular numbers of black and white frames. Indeed in its unprojected formit can be seen to be so. But because the eye cannot quite keep up with frames alternating at or close to twenty-four per second, the frames blur into each other, producing ‘palpitations’. The idea of ‘combinatorial hearing’ transfers readily to films like The Flicker, in which it is the combination of frames which produces specific effects in the viewer, rather in the way that harmonics combine to produce timbre, the tone ‘colour’ of musical instruments. This is in contrast to movies, where shot combinations produce semantic ‘effects’, but rarely perceptual ones: the frame-by-frame combinatorial process is absent.4 In planning the film, Conrad made simple numerical calculations to work out the sequences of black and white frames, but this is not a constructivist or system film:

I did not use an overall mathematical composition or systematic device. Math was used only to compute what certain patterns would look like so that I could pick from them which ones seemed to be the most interesting. The whole film is made up of these black and white frames in order to most vividly embody the concept of pulse modulated light ... There are forty-seven different patterns; some of them were repeated a number of times. Each pattern is based on a twenty-four frame per second (24fps) scheme so that I looked at each pattern in terms of both the number of alternations and the duration (or reiterations actually) of black and white frames.5

What emerges in these remarks, then, is a tension between flickering/pulsing, and duration. This is something which characterises a range of flicker films, but which is particularly developed in the semi-flicker films of Peter Kubelka, discussed below.

Paul Sharits

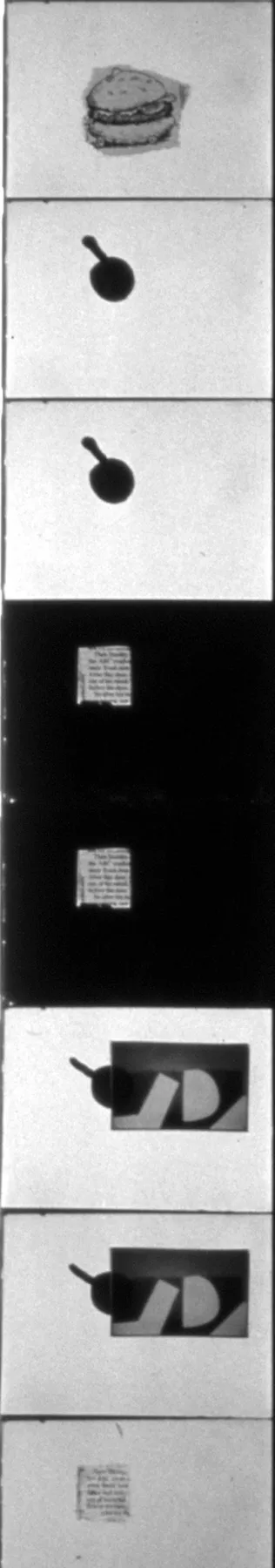

In the same year as Conrad produced The Flicker, Paul Sharits, a graduate design student in Indiana who then became associated with the Fluxus group of artists in New York, was developing his own flicker films. His earliest pieces, such as Word Movie/Flux Film 29 (1966), have images, or text as image in this case, but by the end of this very productive year Sharits had moved into abstract colour work. His films exploit the persistence of vision in a very particular way. Film is a presentation of twenty-four discrete frames per second. The persistence of vision bridges the gap between frames, the moment of blackness when the shutter is closed while the next frame is drawn down into the gate. In Sharits’ films, persistence of vision creates a collision between one frame and the next: one frame is superimposed on its predecessor on the retina. Thus the eye mixes the frames, creating other levels of visual phenomena; complementary colour afterimages, frame ghostings and pulsations, colour mixes and variable degrees of flicker. To some extent all films are constructed inside the viewer’s head, but in Sharits’ films one could say that to a large extent what goes on inside the viewer’s head is the film, and what appears on the screen are mere frames: if the viewer saw those frames only as discrete coloured rectangles, the experience would be massively diminished. There is a qualitative difference between Tony Conrad’s work and Sharits’, that is something like the difference between Bridget Riley’s black and white paintings and her subsequent colour ones. Although The Flicker is a black and white film, it generates colour phenomena in the viewer’s brain. Because it is composed of uniformly contrasting black and white frames it has a more pronounced flicker than Sharits’ films, where adjacent frames may be of different colours but a similar level of brightness. Sharits varies not only the frame-to-frame colour dissimilarities but also the degree of light/dark contrast between adjacent frames, such that the degree of flicker ranges from pronounced to almost imperceptible.

In some of Sharits’ earlier films, such as Peace Mandala End War (1966), representational images alternate with colour frames. These films are polemical, setting out an equivalence between image as representation and image as colour field: ‘Film ... unlike painting and sculpture, can achieve an autonomous presence without negating iconic references because the phenomenology of the system includes “recording” as a physical fact.’6 Equally, these films demonstrate the process whereby individual frames are inflected by their neighbours. Later in 1966, with Ray Gun Virus, Sharits had abandoned the polemic, settling instead into a more subtle and exploratory dialectic between frames of filmed coloured textured surfaces and frames of pure coloured light which were textureless apart from the grain (see PLATE 10). As well as the colour effects that the film generates there are also textural afterimages which carry over into the non-textured frames and vice versa. This carry-over often appears in negative or in a complementary colour, so that one is aware of two layers in the image, but sometimes a texture seems to transfer itself to the textureless frames, creating a compound image which exists only on the retina.7

One can draw an analogy between Sharits’ films and Elsworth Kelly’s shaped, monochromatic paintings. Individually they generate many of the phenomena described above, and when several are seen in a row, further effects result from the interactions of the different pictures. The distinction that can be drawn between what something is and what it does, is dramatised in both Kelly’s and Sharits’ work. Apart from the work of people like Kelly and Bridget Riley, most paintings, certainly figurative ones, are more about what they are than what they do. Feature films are only about what they do. Sharits’ films both are and do, and he has dramatised the question of the relationship between what they are and what they do by producing pictorial versions of some of the films, in which the filmstrip is sandwiched between sheets of perspex. One can look at either and see it equally as what it is, at the same time as wanting to see what it does when projected. This wanting focuses one’s attention on the material/epistemological duality of the film/experience.

In order to expand the possibilities of the abstract language he was developing, Sharits went on to make a series of films for a projector from which the claw had been removed, so that the film was in constant motion throughout its passage through the projector (see Chapter 3). Thus he was able to create true movies, in that the images were actually moving on the screen, as well as on the retina. By this treatment, however, the frame surrenders to motion and blurs into a stream of coloured light.

Intermittent flicker

If Sharits’ films represent an extreme in terms of abstract optical film, they are also paradigmatic because every frame is different, and therefore every frame is a shot: the frames are the images and this is one way in which his film...