![]()

L’Argent

What is L’Argent? A warning sign? A contest between the evil of which men are capable and the infallible beauty of reality? A cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked capitalism? A plea to the world at large to look beyond self-interest? An investigation of the formation of evil?

Why L’Argent?Why would a director in his eighties, a moment when most other film-makers attain a peaceful equilibrium, devote his energies to this particular story? Why would an artist who has, in Durgnat’s words, remained within the ‘sacred sphere’, take a polemical late Tolstoy story (after a career devoted to Dostoevsky) and all but strip it of its redemptive second half?

L’Argent is a film whose every instant feels so utterly alive that it would be hopelessly reductive to boil it down to a trajectory or set of trajectories, whether thematic or formal. It is easily the fleetest of Bresson’s films, almost rocketing past its multiple characters and locations during its brief running time. For the first time, Bresson has set his hero down in the centre of ongoing action, rather than engineered the action around him. And also for the first time, the hero remains an enigma from start to finish. But in fact, we can’t know Yvon in the way that we come to know Fontaine or Michel (from a respectful distance), because he can only be a cog in the machinery of this story, cast aside by the virus of usury and self-protection whose progress it charts. Paradoxically, it is his story by virtue of his diminishment. Does Bresson suspend the possibility of redemption for Yvon? Not exactly. But by shifting the focus from his hero to the forces that overpower him, the difficulty of attaining redemption is given more of a place than redemption itself. What is it, precisely, that constitutes this difficulty?

If there’s one thematic strand that Bresson pulls from the fabric of Tolstoy’s novella, it’s the opposition of city and country, the cold, man-made functionality of the former versus the natural, oxygenated simplicity and wonder of the latter. But whereas in Tolstoy that opposition develops into an intense hatred of the city and all that it stands for, in Bresson it remains an opposition and nothing more: the plain fact of things, both manufactured and organic, and the way people behave around them speak for themselves.

L’Argent opens with a shot of a cash machine’s metal door gliding shut after an unseen transaction, over which the credits roll. Once the door closes, the reflection of a bus runs across the cold steel, accompanied by the sound of the motor. But then, even though the sound of passing traffic continues on the soundtrack, the only thing we see reflected on the door is a solid white streak. An apparently simple image is not so simple after all. Why would Bresson go to the trouble of filming the reflection of a bus passing and then leaving nothing but a white streak in the image, while continuing with the sounds of passing cars? And, since we’re obviously on a commercial street, where are the sounds of footsteps, the chatter of passing people, and the odd, incidental sounds that fill any cityscape (sirens, beeping horns, clanging objects, etc.)?

Close analysis is often scorned by regular cinemagoers, for the simple reason that it prompts its own way of looking at a film, miles from the experience of just sitting and watching a movie. More often than not, analysis leans on metaphor and interpretation, the pursuit of interlocking patterns, a mechanical process at work behind the film that has next to nothing to do with the way that an artist proceeds when he or she is producing something interesting. The physical shock of Bresson forces you into another way of thinking.

On the previous occasions when Bresson has filmed cityscapes (Pickpocket, Une Femme douce, Four Nights of a Dreamer, The Devil, Probably), there is rarely any chatter on the soundtrack, nor are there many stray sounds: our ears become quickly tuned to the subtly disquieting sound of cars in motion. It has a great deal to do with his desire to focus the audience’s attention (which he shares with Hitchcock) through repetition and patterning. Throughout L’Argent’s first half, the sound of traffic provides a sensorial bridge between scenes. What many other film-makers choose to do with images, Bresson does with his soundtrack – he often either fades down from one sound and into another, or executes a sonic ‘dissolve’. But more to the point, a central fact of Bresson’s art, beginning with A Man Escaped, is the sense of action as an uninterrupted flow, largely accomplished by bridging sequences through sound. This practice became even more refined after Une Femme douce, Bresson’s first film in colour, since he decided that colour dissolves looked artificial and wrong.

Visually, on a shot-by-shot basis, Bresson likes to imprint a singularized action on a given space, like a charcoal line on a blank sheet of paper. The body is either traced in its stillness, or draws itself across the screen in a quick, decisive movement. When one discusses ‘rhythm’ in Bresson, it’s closer to the idea of rhythm in painting, much more than a question of ‘pace’, the actual rhythm of action, as in a film by Scorsese or Coppola, or of shot length, as in Antonioni. In Bresson, and this is a trait that he shares with Hitchcock, the length of a shot has less to do with tempo than it does with sensorial emphasis: it’s never a question of a character simply living a moment in time, as it is in most films, but the way one (i.e. Bresson) would experience the feeling of living such a moment. The shot of Yvon’s hand as it releases the waiter’s arm during the scuffle in the café has a family resemblance to the shot of Martin Balsam ‘falling’ down the stairs in Psycho – both are a-temporal, disjointed from any reasonable space–time continuum, and oriented around a particular sensation. The difference is that Hitchcock is strictly functional, never more so than in Balsam’s murder scene, which produces a bizarre funhouse effect that seems completely unintended. In Bresson, the texture, the light, the aura of the moment, the sense of depth produced through sound all come into play. It’s not just people who are bound to objects in Bresson; rather, everything is bound to everything else, and the focal point becomes the absolute acuity of perception itself. This is not lost on the majority of writers who have tackled Bresson either critically or theoretically, but it’s always posited as a matter of ethics, or morality, or spirituality. There’s no denying the aptness of such claims, but they tend to detract from the aesthetic excitement and sensual impact of Bresson’s art.

The café scuffle; Martin Balsam’s ‘fall’ in Psycho

One could neatly sum up the opening by stating that Bresson is digging right into the fact of money, the world around it reflected by and sounded against the steel barrier that keeps it protected. But such a summary ignores the surprise of the cold steel, the sudden excitement of a decisive image, and the magnetizing power of the world around us.

A family dynamic described within seconds

The action of the film proper begins with the opening of a door, the first of many in the film and a constant motif throughout Bresson’s cinema (‘Doors opening and closing are magnificent,’ Bresson told Ciment, ‘the way they point to unsolved mysteries’).10 Norbert, the film’s equivalent of Tolstoy’s Mitya, enters his father’s study to ask for his allowance and then for an advance on the following week. Norbert (Marc Ernest Fourneau) is a porcelain-skinned boy with large, liquid eyes, and a limpid gaze – a perfect bourgeois innocent. His father, far from the monstrous tyrant of Tolstoy’s story, has the self-important air of a banker turning down a loan. Norbert appeals to his mother, a chic creature who obviously defines herself by her looks. Anyone who complains about the lack of acting in Bresson should take careful note of such a scene, in which a whole family dynamic is described within seconds, with a minimum of screen time and detail: preoccupied parents who live in cold luxury and maintain an even emotional tone (dictated by the father) that they’re not used to having disturbed; a boy who feels that he’s owed whatever he wants but has enough sensitivity about him to quietly defer to his parents. It’s a world away from Tolstoy, carefully observant where he is slyly judgemental, and it’s a good lesson in how much most film-makers fail to leave out of a scene, obscuring the essential details that are already there.

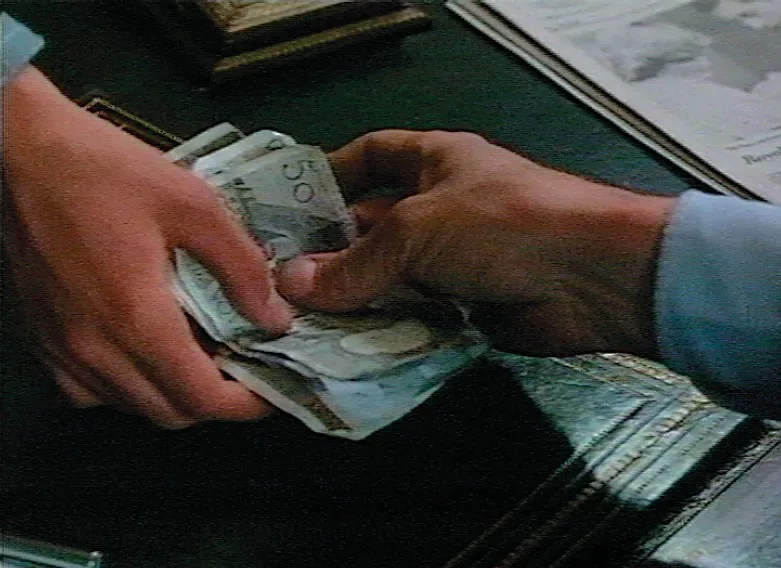

When Norbert’s father hands him the money for one week’s allowance, Bresson shoots the bills in close-up – the exchange of money will be shot in close-up more or less throughout the entire film. One could say that money in this film is a little like the parasite that gets transferred from one character to another via sexual contact in David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1974). But because of the equanimity that Bresson brings to the filming of all objects, money is never imbued with a sense of evil in L’Argent. Bresson is filming a man-made dilemma, and any supernatural or divine influence on events can only be inferred through an interpretation of their overall pattern. After asking his mother for the money, Norbert gets on the phone with his friend Martial (Makhin), and slams it down (Bresson carefully records the decaying ring) as he walks out the door and hops on his mobilette. Here, Bresson executes a sonic fade-out as Norbert rides away, something he will repeat continually throughout the film.

We begin the scene at Martial’s house with a close-up of a watch, which Norbert intends to pawn. The boy who plays Martial is a fair-haired, dark-eyed, proto-malemodel type, with a sybaritic posture and the hint of an ever-present smirk creasing the corner of his mouth. Thus far, Martial is the character who corresponds most closely to his literary prototype, with the crucial difference that he does not appear to be a wastrel. In his Film Comment piece on The Devil, Probably, Olivier Assayas refers to the ‘timeless bohemia’ that Bresson created for that film, with its scenes of hippies strumming their guitars on the banks of the Seine.11 In L’Argent, Bresson performs a similarly abstract operation on an entirely new generation of young people. ‘Perhaps you recall that at [the time of The Devil, Probably] quite a few young people were burning themselves alive,’ Bresson told Ciment. ‘Not anymore. The present generation is not remotely interested in that. Very odd. To them it’s all normal. They belong to an era in which the fact that we are ruining this earth of ours is not shocking.’12 Bresson is of course referring to a cross-cultural phenomenon that anyone who lived through the 1980s should be able to name easily enough – young fogeys, les jeunes cadres dynamiques, yuppies. Just as in The Devil, Probably, only through even more minimal means, he is representing a generational formulation of the world rather than its iconography – Bresson is far removed from the mass cultural preoccupation with labels, styles, ‘events’. And his dramaturgical form, as always, has a distinctly nineteenth-century flavour. What is completely up to the minute is the unconscious tunnel vision, the instantly conveyed feeling that an unfulfilled material need requires immediate action. And Bresson gets the two yuppie prototypes perfectly: the Martial type, completely mercenary, and the Norbert type, the innocent who takes marching orders in wide-eyed silence. The evolution from the student artists in Four Nights of a Dreamer to the unkempt long-haired lost children of The Devil, Probably to the clean-cut, well-dressed bourgeois types of L’Argent is striking: what other modern film-maker has been more sensitive to the youth around him?

There’s always a great beauty to the handling of objects in Bresson’s cinema, with careful attention to weight and volume, and a slowness that gives the action a clarity resembling the ceremonial handling of bread and wine in the preparation of the host (perhaps another reason that Bresson’s cinema is often tagged as religious). Bresson carefully films the action of Martial opening a book, taking a 500-franc bill out and handing it to Norbert (in a match cut) to hold up to the light (‘Pas mal,’ says Norbert, like a kid who’s seen too many gangster movies trying to impress his cooler friend), so similar to Michel’s practice scenes in Pickpocket or Fontaine’s handling of the spoon in A Man Escaped. This is followed by a curious little exchange, in which Norbert leafs through a book of nudes. Martial peers over his shoulder and says, ‘The body is beautiful.’ The exchange originates in Tolstoy’s novella, in Makhin’s references to his beautiful girlfriend, which provides the whole motivation for going to a photo shop and buying a frame in the first place. What counts here is the sense of detachment, the feeling that Martial is a salesman whispering the words in Norbert’s ear, urging him to make a purchase.

The innocent Norbert taking instructions from the sybaritic Martial