- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the conference Africa and the History of Cinematic Ideas held in London in 1995, film-makers, cultural theorists and critics gathered to debate a range of issues. Views were exchanged on such topics as imperialism, and the problems of distribution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

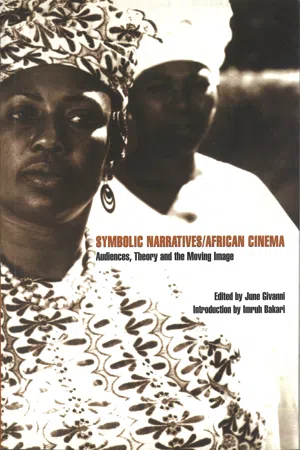

Yes, you can access Symbolic Narratives/African Cinema by June Givanni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Contexts

Chapter 1

Introduction: African Cinema and the Emergent Africa

Imruh Bakari

African cinema at the centenary of cinema in 1995 was widely acknowledged as a cinema that was still 'embryonic even though it has contributed some major works to the universal film heritage'.1 The production of the first films which have established this cinema coincided almost precisely with that epoch when African nation-states were born, and sought to establish themselves within the arena of global politics. The founding of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963 marks this period. The organisation's member states incorporated the entire continent, but the agenda was arguably set by the events in sub-Saharan Africa where, with the exception of Algeria in North Africa, the most volatile and sustained anti-colonial struggles were enacted.

The year 1963 also witnessed the first major film by the Senegalese Ousmane Sembène, Borom Sarret. Though not the first film ever made by an African, its significance lies in its approach to the representation of African life and society, one that was distinct from the hitherto established empire, colonial and ethnographic films popularised by Hollywood and the cinemas of Britain and France for example. Sembène's film was also significant in terms of the alternative narrative conventions which it offered. It suggested a way of storytelling which seemed to indicate the possibility of a distinct identity and aesthetic for a new African cinema.

Of paramount importance however, Sembène and his 'age mates' aimed to establish a new relationship between African audiences and the cinematic image. Over the years their intentions have been voiced at various fora, and have also been the motivation for establishing in 1969 and 1970 respectively, the bi-annual pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou (FESPACO) and pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI). It is in this sense therefore that 'African film-making is in a way a child of African political independence'.2

Since Borom Sarret the idea of an African cinema has gained momentum as a significant number of filmmakers from the diverse cultures and states of the African continent have established themselves internationally. Following Ousmane Sembène, the films of Med Hondo, Haile Gerima, Souleymane Cissé, Kwaw Ansah, Idrissa Ouedraogo, Gaston Kaboré, Safi Faye, Djibril Diop Mambéty and others have become prominent among the body of work now regarded as constituting African cinema.

Much has been written about these filmmakers and their films charting both their growth and their impact on world cinema. In the first instances the apparent objective was to provide some insight into the background of the filmmakers and the conditions under which the films were being produced. Angela Martin's African Films: The Context of Production exemplified this approach.3 Here the concern was to identify the filmmakers and to locate them within an Africa which was to the international audience generally unfamiliar and incomprehensible. Martin's dossier was principally a collection of writings by various scholars who provided African perspectives on the history of the continent, its colonial experience and anti-colonial struggle, its perceptions of the media and film industry, and an indication of film production initiatives as part of the process to counter the pervasive legacy of 'underdevelopment'. Profiles of national experiences and individual filmmakers suggested a complexity beyond the scope of this publication. African cinema revealed itself as not only the 'last cinema', but also one that was sophisticated, yet paradoxical and problematic.

There is no doubt that the cultural and political reality of the continent and the films produced significantly challenged and often contradicted established approaches to cinema. However, international audiences and writers within the North American and European tradition of film theory and criticism inevitably approached African film through what Teshome Gabriel has termed a 'cultural curtain'.4 The challenge was therefore to understand African cinema on its own terms, and to identify the influences and discourses at work within it. Significantly this was not a naive cinema in the sense of a naive art. The filmmakers were not returning to the origins of cinema to re-create their versions of the first Lumière exhibitions. What was to be confronted was a sophisticated and studied use of film technology and conventions to produce films articulating the very modern experiences of contemporary African societies.

The issues thrown up by African films were incorporated into debates around the wider concerns of cinema in the 'Third World'. As the ideas discussed in Questions of Third Cinema indicate,5 the notion of Third Cinema which was formulated in response to developments in Latin America was extended and utilised to provide analytical tools for advancing a critical debate on African cinema. Towards this end important contributions have been made by a number of scholars including Teshome Gabriel, Manthia Diawara, Ferid Boughedir, Frank Ukadike, Haile Gcrima, Mbye Cham, Clyde Taylor, Françoise Pfaff, Ella Shohat, Robert Stam, Pierre Haffner and Guy Hennebelle.

However, African cinema by its intrinsic nature remains problematic. While filmmakers continue to pursue their aspirations, they do so within the highly charged arena of Africa's political economy. What becomes apparent is the paradoxical relationships which must of necessity be negotiated between various means and ends; the filmmakers' international reputation and their domestic existence; and the radical aspirations and the diverse contemporary realities within African societies. Here is to be found 'the contested and dynamic terrain, one that is in constant flux, and continually subject to myriad internal pressures and demands as well as to the effects of a constantly changing global political and media economy'.6

In this global environment the marginalisation of Africa and African opinion is a standing order. The widespread and critical economic circumstances of African nation-states ensures that filmmakers remain collectively disempowered within their respective countries. In effect the circumstances which inform the issues of African cinema debated over the years still remain largely unaltered. There has in fact been very little positive change towards developing a viable infrastructure, providing production finance, and reaching audiences across the continent. In other words, the development of a dynamic African film culture has been acutely inhibited by the postcolonial social and economic condition.

For the filmmakers therefore, the impact of conditions within Africa as well as the prevailing dominance and influence of the international film industry have become points of contention, anger and frustration. With this comes an expressed opinion that the perception and agenda of African cinema is disproportionately determined by the response and reception of African films outside of the continent. In North America and Europe in particular, the work of African filmmakers has been widely acclaimed in arts and academic circles. At international festivals such as Cannes and London, African films have maintained a significant presence. There are also a number of festivals and events, some regular, others occasional, dedicated to or featuring African films.7 While these have brought the work of important directors to international audiences, the effect on the development of African cinema has been regarded with ambiguity.

One rather stark reality has been the relationship between France, through its Ministry of Co-operation Bureau of Cinema, and its former colonial territories.8 As a result of this privileged access to production finance, 'francophone' filmmakers have been able to establish a predominant presence in African cinema. After a number of relatively consistent years the unreliability of this dependency, and the inability anywhere else to establish a viable film production strategy, has placed the issues of African cinema's existence and survival in a critical light, so much so that at the centenary of cinema there was a significant body of opinion which held that 'in spite of the increasing number of African filmmakers and films, in spite of their aesthetic innovations, it is sad to observe that African cinema is at a stand still'.9 The conference Africa and the History of Cinematic Ideas took place against this background. Ironically (and some would say inevitably) the seminal inspiration was not the concerns emanating from Africa or African filmmakers, but the desire of a group of British institutions and individuals to celebrate the arts of Africa in the UK.

The task of planning this cinema event was by no means an easy one. Inevitably the Editorial Group had to make evaluative decisions and develop a rationale for what was finally agreed. In the process of devising the programme it became apparent that in many ways this was a conference waiting to happen. An awareness of the predicament of African cinema came into focus. Like a giant octopus which had wrapped itself into an intriguing web, the idea of African cinema was at once challenging and uncomfortable. The challenge of reconciling the cinema experiences of Egypt, Senegal, South Africa, Burkina Faso, Ghana and Nigeria, for example, in a notion of African cinema was regarded as the inescapable point of reference for a meaningful critical and contextual framework. In grappling with these issues the idea of an African identity presented itself through the prism of the colonial legacies and cultural diversity which has shaped contemporary national identities, along with the ideas of pan-Africanism and diaspora which exist simultaneously, often in contestation.

In view of the acknowledged centrality of cinema and the mass media in popular culture and contemporary society as a whole, African filmmakers have found themselves very much at the forefront of debates around these issues. Addressing African cinema in this context therefore gave the conference a prominent profile within the 'africa 95' season. With this came not only high expectations, but equally a sense of cynicism and exasperation at the idea of yet another conference/festival on African cinema. Indeed there was an awareness that similar sentiments extended to the idea of 'africa 95' as a whole. The objective, however, was to devise a conference that would adequately respond to the complexity and diversity implied by the notion of African cinema. The central question of what is at stake when the words 'Africa' and 'cinema' are brought together became an important point of departure. Broad references to the seminal ideas of the Congolese scholar V. Y. Mudimbe helped to focus and shape the conference.10 Appendix A indicates the outline of the agreed programme, its keynote speech and panels; and the rationale for the preferred approaches to the critical issues and questions.

In her paper, Professor Sylvia Wynter presented what is no less than a substantial archaeology of the location of Africa within the Western tradition of philosophical ideas, and a perspective on the relationship between these and the question of African cinema. Wynter's paper Africa, the West and the Analogy of Culture: The Cinematic Text after Man (Chapter 2) is a challenging exposition and reformulation of many of the seminal ideas which have informed the ongoing debates around the work of African filmmakers. As Ngugi Wa Thiong'o observes in his reflection on the conference, the core ideas being expressed are responding to the acknowledged importance of the cinema, as an aspect of the mass media, in the contemporary world. The principal concern of Sylvia Wynter is therefore its role in securing and consolidating the hegemony of Western (Euro-American) ideology by ensuring and perpetuating the continued submission of Africa and its people to its single memory. The cinema is also a site of resistance and affirmation, thus in response to the question of what is at stake in the formulation of 'African cinema', Wynter explores not simply the oppositional location of an African cinema, but more importantly what could be termed its historically determined redemptive function.

The opening clarifications are pertinent in signalling the need to interrogate the formative ideas which construct the ideological bedrock of the dominant approaches to film theory and criticism. Our attention is drawn to the taken-for-granted commonsense notions which are ingrained within even radical theories of culture and society, including I would suggest contemporary postmodern thought. Here it can be argued that the implicit logic of postmodern discourse, like other post-Enlightenment discourses, locates the African as 'Other' and as a symbol of otherness. Wynter's argument suggests that this is rationalised as a normality within the seminal notion of 'Man', within the definition and evolution of the culturally specific meaning of human society constructed in the course of the historical ascendancy of modern Western society. The idea of 'after Man' therefore is employed to signify a transformative agenda, and the necessity for a new symbolic or...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Part One: Contexts

- 1Introduction: African Cinema and the Emergent Africa

- 2Africa, the West and the Analogy of Culture: The Cinematic Text after Man

- Part Two: Arguments

- 3The Iconography of African Cinema: What Is It and How Is It Identified?

- 4Is the Decolonisation of the Mind a Prerequisite for the Independence of Thought and the Creative Practice of African Cinema?

- 5What is the Link between Chosen Genres and Developed Ideologies in African Cinema?

- 6African Cinema and Postmodernist Criticism

- 7Information Technology, Power, Cinema and Television in Africa

- 8Can African Cinema Achieve the Same Level of Indigenisation as Other Popular African Art Forms?

- 9Audiences and the Critical Appreciation of Cinema in Africa

- Part Three: Reflections

- 10Weapons of Resistance

- 11The Homecoming of African Cinema

- Part Four: Information

- Appendix A Conference Structure

- Appendix B Conference Screenings

- Index

- eCopyright