- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Unforgiven

About this book

In this work, Edward Buscombe explores the ways in which 'Unforgiven', sticking surprisingly close to the original script by David Webb Peoples, moves between the requirements of the traditional Western, with its generic conventions of revenge and male bravado, and more modern sensitivities.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Unforgiven

1

Unforgiven opens as it closes, with a sunset. Outlined against the red sky, a man is digging a grave beside a lonely shack on the prairie, beneath a solitary tree. Sunsets have a special resonance in the Western. It’s the time of day by which you have to get out of town or else, a tradition that goes back at least as far as Owen Wister’s seminal novel, The Virginian, first published in 1903. In ‘Duel at Sundown’, the title of a 1959 episode of the TV series Maverick in which Clint Eastwood appeared as a boastful gunslinger, he gives James Garner just such an ultimatum. But there’s more to it than that. The sun sets, after all, in the west; that’s the direction across the map the pioneers are always travelling, but it’s also metaphorically the direction we’re all travelling (‘We all have it coming, Kid’). One way or another, Westerns are always about death.

Sunset and autumnal leaves

Hence the mood of melancholy with which so many of them are tinged. But this may also derive from the fact that Westerns are set in the past, a past that is gone for ever, cannot be recovered, and so there is often a sense that something has been lost. In the 1960s the mood of nostalgia deepened. Robert Aldrich went so far as to make a picture called The Last Sunset (1961), a title that doubly emphasises that sense of something passing. The following year Sam Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country (1962) set the tone for much of what was to follow later in the decade. Two ageing gunfighters, played by veteran Western actors Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea, get together for one last mission. The west is changing, leaving them behind, relics of an earlier, more chivalrous era. At the end of the film McCrea is shot in a heroic gunfight. As he lies dying the camera cranes upwards to the golden yellow autumn leaves of the Sierras, a metaphor no less elegiac than a sunset. There’s an echo of this autumnal foliage in a beautiful lyrical scene early in Unforgiven, when Ned and Will have just joined up with the Kid and the three ride through a lush and verdant landscape where the trees are turning red and gold, a magical moment before the darkness and storms that lie in store.

During the 1960s, nostalgia extended from regret at the passing of the west towards the genre itself. The production of Westerns in Hollywood fell steeply, down to a mere eleven in 1963, barely 10 per cent of what it had been ten years earlier. For a time this decline was masked by the unexpected phenomenon of the Italian Western, in which, as everyone knows, Clint Eastwood made his name as The Man with No Name. John Ford, informed by fellow Western director Burt Kennedy that Westerns were now being made in Italy, could only respond ‘You’re kidding.’1 But the several hundred spaghetti Westerns made in the middle of the 1960s helped revive Hollywood’s own contribution, not so much in terms of absolute numbers, which remained stuck at an annual figure of twenty or so, but in terms of themes and styles. Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, coming at the end of the decade, is inconceivable without the stylised violence and ideological disillusion of Sergio Leone’s films.

Yet the revival was temporary. As the 1970s progressed, the Western slipped to the margins of Hollywood production. There may be many reasons for this. Audience demographics were changing, with younger filmgoers finding the genre old-fashioned compared to science fiction or the newly reinvigorated horror film. The death or retirement of the genre’s greatest stars accelerated the decline. Ride the High Country had been Randolph Scott’s last performance. None of the other major stars continued beyond the 1970s. Henry Fonda’s last Western was an Italian production, Il mio nome è Nessuno, in 1973. John Wayne and James Stewart made their last Western together, The Shootist, in 1976. It was directed by Don Siegel, and its story, of an elderly gunfighter who knows he is dying, could scarcely be more appropriate, either to Wayne’s own career (he was in fact dying of cancer at the time) or to the melancholy mood of the genre.2

John Wayne in The Shootist (Don Siegel / Dino de Laurentiis, 1976)

The ideological framework within which the Western has had to work has shifted markedly since John Ford’s high-water mark in the mid- 1950s; already by the 1970s many of its certainties were being undermined. In particular, the central figure of the hero, confident in his masculinity and physical prowess, the man who knows what a man’s gotta do, was threatened by an alliance of forces, of which feminism was only the most directly challenging. Even in the 1950s deep-seated faults in the bedrock of American society were causing cracks to appear in the previously impregnable carapace of the male hero. In the remarkable series of Westerns directed by Anthony Mann and starring James Stewart, beginning with Winchester ’73 in 1950, the Western hero is a troubled figure, in the grip of powerful, even irrational obsessions, his emotions barely under control. In the middle of the decade, John Ford’s magisterial The Searchers (1956) cast John Wayne, the embodiment of all that was most dependable and uncomplicated, as a man driven near to madness by his hatreds. Even works by lesser directors, such as Edward Dmytryk’s Warlock (1959), featured heroes, in this case the saintly Henry Fonda, whose motivations were complex and actions not always admirable.

John Wayne in The Searchers (John Ford / C. V. Whitney Pictures, 1956)

By the 1970s, heroism itself seemed a troubled concept. Westerns were now full of anti-heroes such as the comic figure of Jack Crabb in Little Big Man (1970), forever changing sides in an attempt to avoid confrontations. Robert Altman’s demythologising Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976) exposed the venality and cynicism involved in the creation of William Frederick Cody, who first saw the full possibilities of the west as a commodity, as packaged entertainment. Mel Brooks’s irreverent satire, Blazing Saddles (1974), sent up the whole genre. There had been parodies before, but they had been affectionate; for Brooks nothing was sacred. The historical foundations of the genre also came under systematic attack in films that debunked the real-life figures that previous decades had so assiduously built up. In Doc (1971) it was Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, in Dirty Little Billy (1972) Billy the Kid, in The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (1972) it was Jesse James.

In the parallel field of the history of the west, the triumphalist version of western history informed by the notion of manifest destiny, the idea that the white race had a God-given right, even a duty, to expand into the lands which it misleadingly called ‘virgin’ but which were already the preserve of native or Latino peoples, was already being questioned in the 1970s. Possibly this was propelled by events in Vietnam, which undermined America’s imperialist ambitions. In 1987 Patricia Nelson Limerick’s The Legacy of Conquest mounted a full-scale assault upon the theories of westward expansion that had so far dominated the field and which originated in the so-called ‘frontier thesis’, first formulated by Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893. Limerick charged that this account (which saw America’s social and political virtues, identified as adaptability, ingenuity and energy, as deriving from the free and easy life of the frontier) left out a great deal, in particular the contribution of women and of ethnic minority groups, and was over-celebratory, ignoring much in the history of the west that was shameful or disastrous.

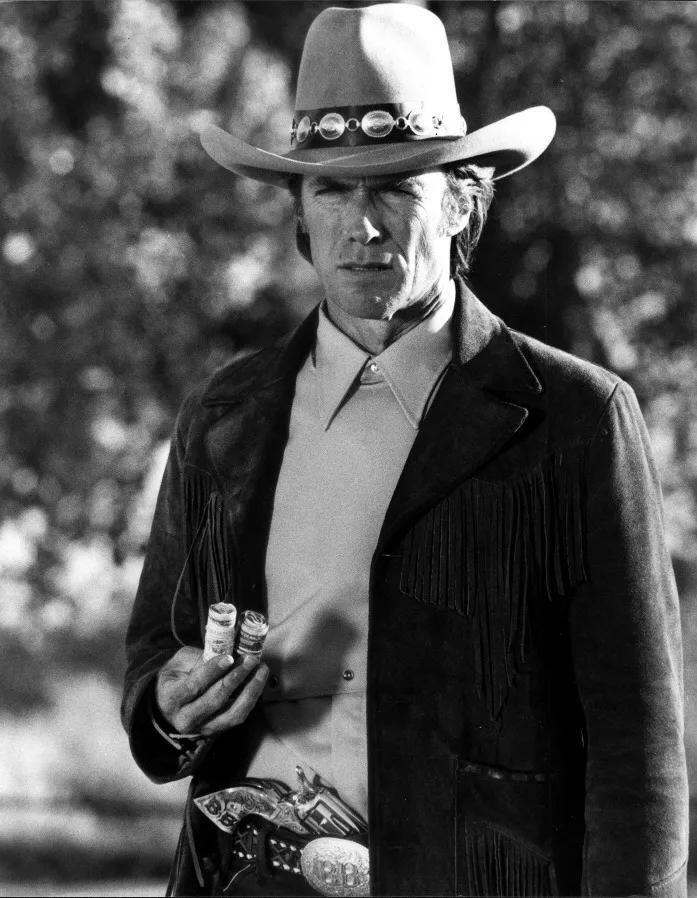

In this context, it seemed, only Clint Eastwood had the necessary star power and vitality to ensure the Western’s survival. From his first leading role in a Hollywood Western, Hang ’Em High in 1968, he was to make a total of ten Westerns up to Pale Rider in 1985. If this could scarcely compare with the productivity of earlier stars (Randolph Scott made no less than thirty-nine Westerns between 1945 and 1962), it meant nevertheless that Eastwood was almost single-handedly carrying the genre upon his shoulders.3

Hang ’Em High (Ted Post / Leonard Freeman Productions, Malpaso, 1968)

There is hardly space to trace in detail Eastwood’s career as a Western hero,4 but what is most striking, beyond the deepening of the actor’s and director’s craft that has marked his progression, is the extent to which he has been alert to the shifts of tone and perspective which have been forced upon the genre over the past third of a century, as the result of changes both within the cinema and without.

Josey with entourage in The Outlaw Josey Wales (Clint Eastwood / Warner Bros. / Warner Home Video, Malpaso, 1976)

As the above dates suggest, the Western film was in some respects in advance of the historians on the question of manifest destiny, having already done something to redress past imbalances in respect of the Indians and other ethnic groups, and readily acknowledging that the west was often a dark and dirty place. Eastwood’s Westerns were alert to these currents from an early date. As we shall see, the role of women in his films, including his Westerns, underwent a subtle development over time. But in other respects too his films did not simply recycle the traditional versions of the Western myth. In The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) Eastwood as the eponymous hero, starting as a loner, as Western heroes traditionally are, gradually collects around him a disparate group of individuals, who include several women, an elderly Cherokee with a delightfully ironic take on the role of the Indian, and a stray dog. Bronco Billy (1980), set in the present day, has Eastwood playing the owner of a wild west show whose innocent, even childish belief in ‘Western’ values is tested almost to destruction by the cynicism of those around him. In Pale Rider, Eastwood’s last Western before Unforgiven, his role is certainly heroic, leading a group of gold-miners in their struggle against a heartless corporation. But there is something ultimately unhealthy about the hero-worship he attracts, in particular from a young girl who convinces herself she is in love with him, while in its focus on hydraulic mining and the damage it does to the environment, the film echoes the increasing consensus of the ‘new western historians’ that economic development in the west was frequently rapacious and destructive.

Bronco Billy (Clint Eastwood / Warner Bros., Second Street Films, 1980)

Little Bill is confronted by Alice

Hydraulic mining in Pale Rider (Clint Eastwood / Malpaso, Warner Bros. / Warner Home Video, 1985)

What all these films indicate is that Eastwood has been alive to the changing social milieu in which the Western...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Unforgiven

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Unforgiven by Edward Buscombe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.