![]()

‘Do the Right Thing’

No doubt this film is gonna get more heat than any other film I’ve done. I know there will be an uproar about this one. … We’re talking white people and racism in a major motion picture. It will be interesting to see how studios deal with it. This film must have a wide, wide release. I have to have major assurances going in.

Spike Lee1

1

As he suggests in this opening inscription, Spike Lee draws upon a number of skills as writer, producer, director and marketeer to push his films to popular success. But perhaps more than anything else among his many talents and attributes, Lee is an issues-oriented film-maker whose work is always, in some way, grounded in collective, social values. Indeed, the controversies and representational politics of urban blackness are his fortune. All of Lee’s films radically and thematically depart from one another, each marking a break with the style and content of its predecessor, with each film situated in its particular historical moment, attendant set of issues and circumstances of production, with none adhering to a particular formula or genre. Significantly, each of Lee’s films is organised around a social issue, political conflict, or a personal theme, mixed with an insightful rendering of the subtle nuances and rhythms of African American culture and urban life. Additionally, while the Lee strategy of portraying the dramatic tensions built around an array of conflicts with personal and social consequences is hardly new to the film industry, Lee has been quite adept and successful at feeding off the media attention generated by the controversies surrounding many of his productions. Not incidentally, this high media visibility has greatly contributed to Lee’s star persona and public caché as one of America’s most recognisable and prolific film makers, and even the most cursory examination of these debates and polemics is revealing.

The controversy over School Daze (1988) erupted when Lee’s satirically frank depiction of the colour and caste contradictions of black collegiate life (the Wanabees vs. the Jigaboos) didn’t agree with the conservative ‘uplift the race’ vision of the administration of Moorhouse College. Consequently, Lee, a third-generation Moorhouse man, was denied use of the college as a location in mid-shooting schedule. With Mo’ Better Blues (1990) came accusations of anti-semitism, prompting Lee to rebut these claims in the public forum of The New York Times.2 The release of Jungle Fever (1991) raised criticism that Spike Lee’s personally narrow views on interracial romance had doomed Jungle Fever’s adventurous ‘mixed’ couple, while simultaneously fetishising and selling the allure of interracial sex and contrasting skin colours.3 Besides running over studio-imposed budget limits and confronting an array of money issues, the filming of Malcolm X (1992) was further complicated by public debates with a number of black critics (Amiri Baraka and bell hooks notable among them) over just who has the ‘cultural authority’ to film Malcolm’s life, and from what historic, social, political, or gendered perspective.4 In fact, film industry, media and critical strife generated by the production of Malcolm X became so intense that Lee was inspired to inscribe the film’s accompanying production book, By Any Means Necessary: The Trial and Tribulations of the Making of Malcolm X, with the insurgent subtitle ‘with fifty million motherfuckers fucking with you’.5 Closing the decade, Summer of Sam (1999) provoked the ire of some Italian Americans and again raised the perennial ‘cultural authority’ debate over just who has licence to represent a given social collectivity or identity. Bamboozled (2000) further challenged and complicated issues and debates concerning the cinematic construction of blackness by painfully (and playfully) exploring the resurrection of the ‘coon’ stereotype and minstrelsy in the media. Broadly then, Spike Lee’s features reveal a restless, developmental experimentation and creativity over what is an ongoing, successful and fast-moving trajectory of issues-focused films made increasingly popular by media-hyped public debate and controversy.6

Malcolm X

Summer of Sam

As Lee refuses to dwell long on any specific genre, formula or style, a few constants feed his vision and sustain his work: his commitment to depicting an intimate, nuanced view of contemporary African American culture; his engagement with hotly contested issues of politics, social power, and identity; his persistence at maintaining his momentum over a series of films as he says ‘like the white boys do’; and his insistence on not being ‘chumped off ’ by the film industry, but on ‘getting paid.7 ’

2

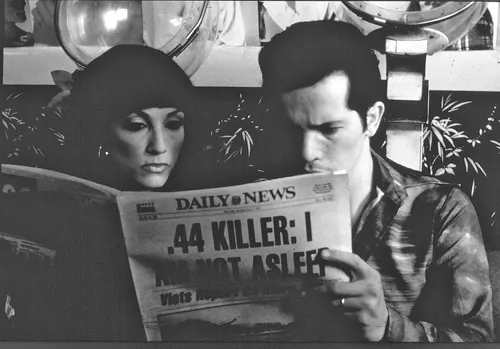

Released 30 June 1989 and falling between the grandly ambitious but somewhat uneven comedy-musical School Daze and Lee’s exploration of jazz, romance and patriarchy Mo’ Better Blues, Do the Right Thing was much anticipated, widely praised, denounced and debated, clearly drawing more media attention than any other film that summer season of commercial releases. In terms of engaging the politics of race, representation, cultural difference and power, Do the Right Thing couldn’t have arrived at a more turbulent and opportune, media-focused moment locally, nationally, internationally. Locally, New York City had already been rocked by a series of racially charged incidents including the dramatic and questioned Twana Brawley rape case, the violent and sensationalised rape of a white jogger in Central Park by a group of black youths, as well as a long ongoing series of starkly racist, mob killings of African Americans, notably including Michael Griffiths and Yusuf Hawkins whose names were invoked in the film’s opening. Adding to the city’s tense mix of race, identity and politics, Lee openly remarked on several occasions that he hoped Do the Right Thing would sway the upcoming mayoral election by convincing black voters to unseat then-mayor, Ed Koch, whom he blamed for New York’s poisoned racial climate. In one of Lee’s many visual details and astute touches that centres the film in the controversies and political contests of the day, the public address of Do the Right Thing’s wall graffiti plays with the slippery, contingent qualities of mass mediated truth. Lee proclaims with situational irony, on one wall, that ‘Twana told the truth’, while declaring with literal intent that the voting public should get out the vote and ‘dump Koch’ on another.

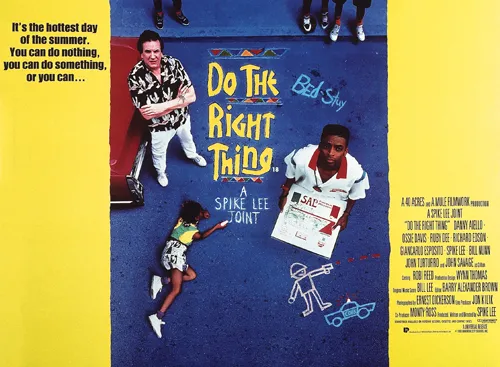

The release poster

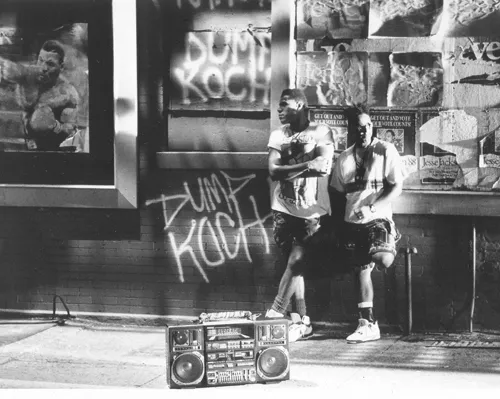

Political graffiti

The charged, political, critical and media atmosphere at Do the Right Thing’s moment of release was, also, partly energised by sharply exploding controversies in the realms of American art and cultural production, as the nation’s political right wing (coincident with a worldwide upsurge of religious fundamentalism) became politically visible and increasingly vocal about policing issues of ‘decency’ in the arts, humanities, and popular forms of cultural production and consumption. With the slow disintegration of the Soviet Union and its alliances, and the fall of the Berlin Wall marking the official end of the Cold War, the United States was left with no grand ideological scheme or external counter-point, superpower enemy, to define, unify and defend its citizenry against. Thus the complex weave of political debates and tensions between America’s Left and Right, rich and poor, white and non-white, straight and gay, tended to sharpen and implode, focusing on escalating struggles over religion, culture, class and an array of identity and group differences.

The specifics of this debate erupted into open strife in the US Congress as legislators fought over the use of public money for what the political and religious Right deemed as ‘indecent’ controversial art, principally funded through the National Endowment of the Arts and the National Endowment of the Humanities. From a Congressional uproar over public funding for Andres Serrano’s sculpture Piss Christ (a crucifix suspended in a bottle of urine), to public outcry and political pressure forcing the cancellation of The Perfect Moment exhibition, containing Robert Mapplethorpe’s controversial homoerotic photos at Washington DC’s prestigious Cochran Gallery, battles over taxpayer funding of the arts raged in both national legislative houses. This battle also rippled through the commercial sector, from Pepsi Cola’s dropping Madonna from a lucrative endorsement contract over the potent mix of erotic fantasy with religious ecstasy in her music video ‘Like a Prayer’ to Martin Scorsese’s unflattering, to some blasphemous, rendering of Jesus in his film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). And on the international front, Iranian clerics issued a death sentence, or fatwa, against renowned author Salman Rushdie for his novel The Satanic Verses which they deemed an insult to Islam.

Across a broad contested terrain, then, the end of the 80s brought America’s right wing discourse on ‘traditional family values’ tagged the ‘culture wars’, aimed at policing the moral content of public art and culture to its highest point of expression and controversy. This high moment of the ‘culture wars’ also had a distinct black dimension to it: some in Congress protested the use of Public Broadcasting System money to fund Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied (1991), a breakthrough, poetic documentary exploring the possibilities of a straight-gay ‘brother to brother’ dialogue, with open proclamations of homoerotic love between black men. Consonant with the same tone of backlash, Langston Hughes’s estate supported by a faction of irate, conservative black literati attempted to block the US screening of Isaac Julien’s short feature Looking for Langston (1988), a dreamy, erotic meditation set in the Harlem Renaissance and celebrating Hughes’s clandestine homosexuality. The end of the 80s also saw an unlikely alliance between some African American civic and church leaders, and America’s white neo-conservatives aimed at proscribing the lyrics and attitudes of young black hip-hop and rap performers. So it was in this time frame and charged atmosphere of political and cultural conflict that Do the Right Thing came to spark more media attention and critical debate than any other film in the history of black American film-making (with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song [1971] perhaps taking a worthy second place).

Always pushing Do the Right Thing’s promotion and his public persona as director, actor, celebrity, that summer Spike Lee loomed large in the media, appearing on the covers of three national magazines including Newsweek and The Nation. But perhaps Lee appeared most tellingly on the cover of American Film, where, signalling his commitment to desegregating yet another American enterprise, he posed in a Dodgers’ uniform (Jackie Robinson’s, no less) leaning forward and set to pitch a wicked, social curve-ball, and in an act of symbolic conflation moved the contested terrain of racial exclusion from baseball of the past, to the ‘now’ of the commercial film industry. Moreover, Do the Right Thing’s social and political influence was deemed important enough to impel both The Oprah Winfrey Show and Nightline to devote entire programmes to the film’s broad reception and social impact. The New York Times ran at least five articles, a symposium of critics and experts on cinema, violence and race, a couple of Sunday features, as well as several reviews of the film. As noted by the flood of reviews, Spike Lee interviews, cameos, bios, photo opps, and various articles weighing the impact of the film’s social, political and aesthetic representations, all the major papers in the country debated Do the Right Thing, taking positions somewhere between, or at, one of the extreme poles of opinion – with the film deemed socially diagnostic and prescient, at one end, or a d...