![]()

1 Power Pop

Pixar Studio’s 1995 film Toy Story, like many great works of popular culture, sustains a dynamic vitality, at times even vulgar and anarchic. It proved instantly appealing to audiences, who continue to find the film engrossing and invigorating. Through its wild innovations and surprising story, the film engages a utopian spirit of freedom and imagination, suspending us from our conventional expectations by celebrating our capacity to dream (toys springing to life). The film galvanises our facility to envision alternative realities and different perspectives, seeing the world afresh from another scale and conjuring up our own memories and spirit of childhood play.

It became the top earning film of 1995 and racked up three Academy Award nominations, including one in the Best Original Screenplay category, a first for an animated feature. The film’s commercial and artistic success launched computer animation as an exciting new medium, creating a successful alternative to Disney that inspired more companies to invest in animated features, thereby contributing to what many considered a new golden age of animation.

Toy Story’s two sequels distinguished themselves no less than the original, as the central themes of the first film gained even greater emotional depth in each iteration. The second film demonstrated a capacity to combine surprising and enticing action while remaining faithful to the original’s expressive currents. The third film developed the original movie’s theme of loss into a stirring exploration of maturity and closure.

Playful in its own artistic expression and experimentation, Toy Story celebrates the free rein of play. All types of play surge through the film: creative play, play-acting, devious play, artistic play. Play remains one of the film’s core themes and values. For the main characters, getting played with amounts to their raison d’être. In turn, to inspire their artistic work, the film’s artists revisited their own childhoods, recalling the inventive and sometimes twisted play they themselves engaged in as kids.

Compared to Disney’s great animated features, with their fine arts style and fairy-tale naturalism, Toy Story looks like a veritable work of Pop Art, dominated by glossy, brightly coloured commodities, the film’s artists relishing in their glimmering, reflective surfaces: vibrant toy packages with shiny, transparent windows; glowing primary colours; rounded, precisely moulded, industrial plastic forms. As with Andy Warhol and other Pop Artists, the Pixar film-makers sought to counter or challenge the dominant conventions that had developed in their respective mediums. Representing the commercial world around them (the world of movie or television tie-ins and the crass commercial drive of toys aimed at the impulses and imaginations of children), rather than the sanctified and sacral realm of fairy tales and classic stories (the stuff of Disney dreamscapes from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to Beauty and the Beast), amounted to an immediate avoidance of easy sentimentality. The Toy Story film-makers did not necessarily draw upon the inspiration or influence of the Pop Artists (though I reserve this argument as a possibility); rather, they retained a commitment to related motives, within their respective mediums, and analogous inspiration, similarly recognising the graphic and formal vigour of industrially manufactured commodities, and confronting and conceding the role of commercial products in our lives.

Take one shot as an example of Toy Story’s Pop Art parallels. It depicts Buzz Lightyear at the Dinoco gas station and features a stunning utilisation of angles and composition to generate energetic geometric shapes out of the commercial space and products within the frame. Constructed from below Buzz in a medium shot, the perspective establishes strong lines in the background from the two beams opposite the gas pump, as these red vectors jut into the centre of the frame. Even more dramatically, the beams carve out sharp angular forms accentuated by the dynamic play with Pop colours, from the green, white and yellow squares on the pump, to the roof’s white cubic and triangular shapes offset by the beams and pump, to the shades of red on the columns, all visually rhyming with the greens and whites on Buzz’s shimmering spacesuit. It presents an exhilarating, glistening replication of an entirely artificial subject and environment, a dazzling evocation of the allure and effervescence of a commercial world. And it does so by respecting the veneer of these products of commerce, honouring the vigorous precision of their impeccable design.

Pop Art: dynamic evocations of an artificial, commercial world

By contrast, Disney’s animated films typically featured lush, green topography or natural settings, from the pastoral scenery of Bambi (1942), The Jungle Book (1967) or Sleeping Beauty (1959) to the vivid fantastical seascapes of The Little Mermaid (1989). Disney animators worked within a fine arts tradition, creating characters with mimetic, if idealised, figurations and using colours that hew closely to a natural spectrum. Backgrounds retained subtle tones (close in value) through carefully controlled gradations – airbrushed colours, rubbed-on blends or stoked drybrushes – so as not to distract from the characters and action. A woodland glade, for example, would retain balance through shading on trees at the edge of the frame, with airy light at the centre to highlight the main characters, and green (diffused only through a narrow spectrum of the colour’s range) modulating the background. The picturesque village in Disney’s Pinocchio (1940) unfolds like a moving illustration in a classic work of literature: fine lines and shading delineate the bricks and stones in the buildings, with washed browns and yellows hinting at their rough facades; while hand-drawn lines and brushed shading blend the tile roofs. These tactics typify the tendency of classical Disney artists to romanticise nostalgic sets by employing soft edges and balanced colour and lighting tones. Disney’s artistic references – Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Maxfield Parish, amongst others – consistently looked towards nineteenth-century book illustrations and classical artists whose work retained strong narrative clarity.

In drawing so heavily on illustrational styles of the previous century, Disney animation developed an almost anachronistic aesthetic in relation to this modern medium – modern in regards to the motion-picture technology enabling animation as well as some of the inventions (multi-plane camera systems) and innovations (for example, Rotoscoping) employed by the company – and, indeed, to modern art. The connections to organic forms – lush, natural landscapes, anthropomorphic animals, folk-tale heroes and heroines – suggested continuity between our imagined idyllic past and the modern age. In turn, from The Jungle Book to Aladdin (1992), from the Three Little Pigs (1933) to Cinderella (1950), from Peter Pan (1953) to Pocahontas (1995), Disney’s animated films drew upon well-established cultural references: folk tales, fairy tales, fantasies and literary classics. The pastoral colour palettes and simple figurative characters – often animals – illustrating these traditional stories registered a visual match to the literary material and sensibility.

Toy Story offers a complete upending of this paradigm, from its visuals – hard-edged, commercial design; primary colours; metropolitan and suburban landscapes – to its rejection of fairy-tale or folk-tale narratives. It abandons traditional cultural references, and therefore also the typical Disney practices, and instead offers critical deconstructions of popular culture, reconfiguring commercial toys and archetypes of Americana like cowboys and astronauts in a contemporary, urban setting. In this sense (and many others), Toy Story completely discarded the Disney model, opting instead to represent the modern age itself, while also deliberately eschewing painterly gestures, a decisive rejection of nineteenth-century aesthetics and the Disney style.

Toy Story also flipped the conventional Disney relationship between films and their ancillary merchandising. Disney, like other studios, produced merchandise of their fairy-tale and folksy characters (stuffed dolls from Jungle Book; plastic figures of Ariel from The Little Mermaid), a tactic extending all the way back to Mickey Mouse products. These toys referenced the story world of the films and brought that world into the lives of children. By contrast, Toy Story takes merchandising as its very subject and projects it into a narrative world. If a Little Mermaid toy refers back to the film, conjuring up its narrative and defining the toy’s personality, then Toy Story self-reflexively explores the world of toys qua toys. It represents an acknowledgment of the significance of toys (industrial commodities) as things-in-themselves (rather than merely as signifiers of the narrative world from which they are derived). Toy Story shows how these commodities retain significance for their owners through their use and the personal meaning (say, a favourite toy) the user invests in them.

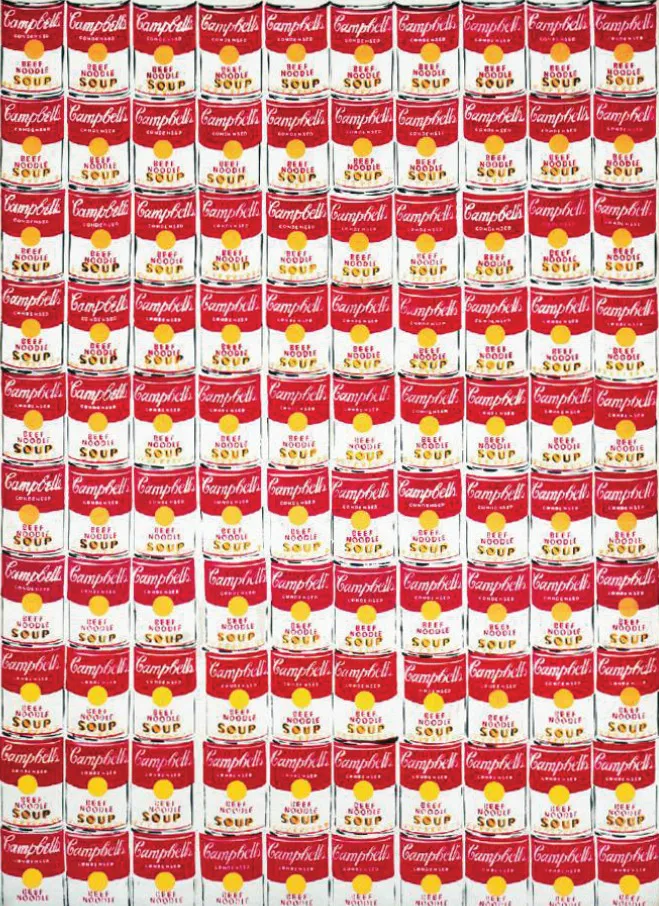

A shot from Toy Story 2 (in a scene which drew upon elements from early screenplay drafts and concepts for the first film) explicitly addresses this issue through its invocation of Pop Art compositional logic. When Buzz stumbles down an aisle in a toy store, he stands in awe at a wall of shelves teeming with packages of Buzz Lightyear toys. The film-makers frame the shot almost head-on to emphasise the serial forms and lines, the seemingly endless volume and reproduction of the product creating a vertiginous symmetry. The shot, of course, echoes Andy Warhol’s large canvas of Campbell Soup cans (‘100 Soup Cans’ [1962]) and parallels its effect: a straightforward explication of the replication function of the industry of commodities, if also underscoring the subtle abstract beauty created by the repetition and symmetry. Yet even this beauty remains implicated within the stark truth of the sameness of the products. Both images share this recognition and revelation.

Likewise, both compositions acknowledge that ordinary objects, important in our everyday lives, remain mass produced, generating similarly significant meanings in a massive number of other individuals, an enormity of engagement that nonetheless fails to render them – or the individual commodity – meaningless (in fact, as if to emphasise this point, one of the other Buzz figures in the packages comes to life as well, recalling the first film’s Buzz and suggesting a seemingly infinite amount of ‘toy stories’). By taking popular commodities as their subjects, both compositions identify the meaning that the products retain in our individual experience while also admitting the commercial industry – and mass production – that plays a role in this meaning and our lives.

‘100 Cans’, Andy Warhol, 1962

With their solid colours evenly distributed on the surfaces of the objects, and their immaculate contours and form, as with industrially moulded colours and plastic, the commodities in Toy Story matched the strengths of computer animation. Utilising programming that more easily rendered surfaces with smooth, uniformly coloured design and consistent shape, this new medium worked better with inanimate objects. It struggled with more complex textures like skin or rough, variegated surfaces. Computer animation’s sensitivity to surfaces, to plasticity and rubber, even artificiality, confirmed the film-makers’ decision to take toys and plaything products as their subject, even while this choice remained driven by their deep dedication to popular culture.

When Mr Potato Head reconfigures his face in a disarrayed arrangement of its features – eyebrows tilted sideways, mouth askew, nose high atop his left cheek, eyes running down one side of his face – and the savvy spud announces, ‘Look. I’m Picasso,’ the film-makers are flagrantly flaunting their love of classic toys and pop culture by accentuating their distinction from high art. In other words, the cultural reference establishes their cognisance of a consecrated artist and artistic practice (Picasso and experimental modernism), and by doing so, signals the self-consciousness of their choice to work with a decidedly lowbrow subject like Mr Potato Head. The great Pop Artist Roy Lichtenstein followed a similar logic in his own ridiculously witty variations on Picasso such as ‘Woman with Flowered Hat’ (1963). In this work, the artist insolently paraded his style by evoking Picasso to highlight the decided departures from high art taken by his own work and that of his Pop cohorts. In similar fashion, the spud’s allusion to high art only flaunts his status as a manufactured toy. While the gesture certainly works as a wink to the film’s informed audience, it also invites them to share in the same refusal of certain aspirations to high art taken by the film-makers and delight in their own love of a popular product like Mr Potato Head.

Like folk artists, who acknowledge the place of popular products in our lives, the Pixar team and Pop Artis...