- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

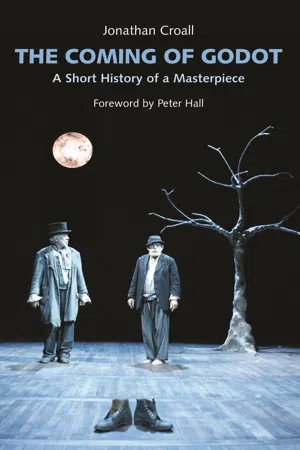

Fifty years ago Sir Peter Hall directed the English language world premiere of Samuel Backett's Waiting for Godot. Now he has returned to this extraordinary classic, the quintessential absurdist piece that has become one of the most important works of modern drama. Jonathan Croall, who had access to rehearsals for this landmark anniversary production, combines an account of this theatrical journey with an informative history of the play that has intrigued, baffled, provoked and entertained all those who have ever come across Vladimir, Estragon and the ever elusive Godot. Foreword by Sir Peter Hall.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Coming of Godot by Jonathan Croall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & British Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Readthrough

Monday 4 July

In the main rehearsal room in the Clapham community centre, I am sitting at a table with Peter Hall, the Waiting for Godot cast, the creative team, members of the stage management, and Danny Moar, the director of the Theatre Royal in Bath. The production is to open in Bath in just over seven weeks’ time, as part of the Peter Hall Company’s third season in the city. It is the fourth time he has directed the play, the most recent productions being at the Old Vic in 1997 and the Piccadilly in 1998.

Before the actors – James Laurenson, Alan Dobie, Terence Rigby and Richard Dormer – start on the readthrough of the play, Peter offers some preliminary thoughts.

It is of course impossible for me to completely start again on this play, and to say there won’t be similarities to my two most recent productions. At the same time I don’t like the word revival: it sounds as if you’re breathing air into a corpse. So I want to go back to what we did before, and then change it. The main problem will be to bring the verbal and physical life together, so we must do that as soon as possible.

It’s a play I feel I’d like to re-visit every five or ten years, it’s that good. It’s very poetic, very ambiguous, and it changes its meaning from decade to decade – as it should, because every work of art has that quality of being many-faceted. It comes out differently every time I do it, because it’s different times, different actors, different audiences, different stages – and I’m different, though I don’t know how.

Great theatre is always a metaphor. All we know here is that there are two men on a road by a tree, waiting for someone to turn up. It’s a great metaphor for living, for the search for faith, for purpose. But I think it’s erroneous to think there’s a single meaning – a metaphor is a metaphor, and it means different things to different people. If you said to Sam, What does this mean?, he would reply, What does it say? By that he meant, What does it mean to you?, not what it might mean to him. He wouldn’t get into that area at all.

People are disturbed by the play, because it has a very realistic pessimism about it. Yet it’s so pessimistic that it ends up being optimistic: people come out feeling better because they have gazed at human reality. The reason I think is the courage of the two men, waiting day by day, and the humour, which is very heart-warming.

The script we’re using is the one printed in The Beckett Notebooks. Sam went on chipping away at the text, cutting some of the more absurdist material, and this represents his final thoughts. He made a lot of alterations, and it’s the play in its most sinuous form: it’s more coherent than earlier versions, it avoids the ridiculous. It’s lovely how he’s stripped it down, and taken all the weeds out.

The main components of the play are the extraordinary metaphysical language of the writing, and the body language of the action. Beckett loved mime, he loved clowns, and a lot of the play is about mime. Another component is the humour, and what I’ve got to do in the coming weeks with you is to make the comedy and all the cross-talk precise, as precise as if I were working with Morecambe and Wise.

As a director I think it’s terribly important that we don’t make what Pinter describes as ‘a bit of statement’. A statement is not usually ambiguous, it usually enforces its meaning. Godot doesn’t do that: like all great plays it’s essentially ambiguous, so you’ve got to allow many possibilities to come in for it to be credible. I say credible rather than truthful, because I like less and less the word truthful. There’s nothing true about the theatre, it’s artificial, that’s the point of it. Whereas credible it can be.

He then suggests that the actors read the play, and that all except Terence Rigby, who’s playing Pozzo, use Irish accents. Rigby and Alan Dobie as Estragon are repeating the roles they played in the 1998 production, and their assurance is soon obvious. But as Act 1 is worked through, the other two actors quickly enter into the spirit of the piece. James Laurenson as Vladimir shows great energy, and in the exchanges with Estragon there are all the signs of a good rapport, the two actors making continual eye contact in order to pick up the cues speedily. Richard Dormer rattles through Lucky’s extraordinary monologue with astonishing pace and accuracy, while Terence Rigby’s measured reading of Pozzo already exhibits considerable menace.

‘I love the energy and speed, but it’s a little too fast for comfort,’ Peter says between the acts. ‘A lot of it is in the pauses, but you have to earn those pauses.’ The actors start to take this criticism on board during the reading of Act 2. Once they finish, costume designer Trish Rigdon passes round some preliminary costume sketches, and designer Kevin Rigdon unveils the set model. It’s an appropriately simple set: a road, a tree and a rock, with a moving panel in the dark-blue background that will open at the end of each act to reveal the moon.

Finally, Peter raises the question of the rehearsal schedule. This week is going to be tricky for the actors. The first two plays in the Bath season, Private Lives and Much Ado About Nothing, are now previewing, and will have their press showings on Wednesday, which Peter will have to attend. The second two, Shaw’s You Never Can Tell and Waiting for Godot, he plans to rehearse in tandem, ‘an idiotic position to put myself in’, he confesses. As the Shaw play will start previewing a week earlier than the Beckett, he will focus on You Never Can Tell this week, leaving his assistant director Cordelia Monsey to do some basic groundwork with the Waiting for Godot company. A matter then of Waiting for Peter…

2 Down-and-Outs in Paris

‘Becket does not want his actors to act’ – Jean Martin, the original Lucky

In 1949 Roger Blin, a stage and screen actor well steeped in the avant-garde, was just beginning his career as a director in Paris. A friend of the theorist Antonin Artaud, Blin had been alerted to the existence of En attendant Godot by the Dada artist Tristan Tzara, who had read and admired the play, and advised Beckett to show it to Blin. Beckett’s partner Suzanne Descheveaux-Dumesnil duly took the script round to the Théâtre Gaîté-Montparnasse where Blin was working. Blin thought it highly original, a play that seemed to question the very basis of theatre. He loved its mixture of comic and tragic elements, and Beckett’s ‘gift for provocation’, which he felt would shake a lot of theatre people. ‘I read it without understanding it very well,’ he recalled, ‘but I felt a kind of mysterious voice which shook my natural laziness, which said it must be put on, and I must direct it.’

At the time he was working on Strindberg’s difficult play The Ghost Sonata. Beckett came to see the production several times and liked what he saw, feeling Blin had faithfully followed the playwright’s intentions. Blin later joked that Beckett was impressed by the fact that the theatre was half empty, presumably believing that a small and dedicated band of theatregoers would provide an ideal audience for his own work. The two men met to talk about the possibility of a production. Finding a shared interest in the comics of the silent screen and in Irish theatre, especially the plays of J M Synge, they hit it off immediately, beginning a lifelong friendship. Blin had by now also read Beckett’s first play Eleutheria. This was a more traditional work, with seventeen characters, elaborate props and complicated lighting, and like Waiting for Godot was unperformed. Blin said it would be impossible for him to put it on, as he was poor and had only limited resources, but that he could stage En attendant Godot, since it required only four actors – who could, if necessary, wear their own clothes – and nothing more than a spotlight and a bare branch to signify a tree.

After months of trying to place the play, Beckett felt this was his last chance, and agreed to let Blin have it. Unfortunately, the managers of the Gaîté-Montparnasse were not enthusiastic about staging it. Blin then spent the best part of three years trying to find the right theatre, and raise financial backing for a production. The breakthrough came when the French government decided to offer small grants to cover the costs of the first production of new plays in French. When Blin applied for a grant, the minister for the arts, Georges Neveaux, wrote back: ‘You are quite right wanting to direct En attendant Godot. It is an astonishing play, needless to say. I am fiercely for it.’ With his key support the application was successful, although the money was only just enough to cover the actors’ wages and the cost of the poster.

Even then it took a while to find a theatre willing to stage the play. An agreement was signed with the Théâtre de Poche, but the arrangement fell through. The small Théâtre de Port Chasseur did actually schedule it, but then insisted that Blin dispense with the crucial tree, which he refused to do. Finally Jean-Marie Serreau, the manager of the Théâtre Babylone and a pioneer of the French avant-garde, offered to mount the production. Serreau, well-known for his adventurous choice of new plays, was deep in debt and his theatre threatened with closure, but decided that if he was ‘going to shut up shop, why not go out on a high note?’ A few private individuals, including the actress Delphine Seyrig, put money into the production.

In its knockabout and comic elements Waiting for Godot reflected Beckett’s youthful interest in the music-hall and the circus, as well as his delight in the silent-screen antics of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Ben Turpin and Harry Langdon. In Blin’s mind the ideal casting would have been Chaplin as Vladimir, Keaton as Estragon, and Charles Laughton as Pozzo. But in reality he found the play difficult to cast. Several actors turned down parts because they couldn’t understand the play, or believed no one would come to see it; others accepted, but then left after further delays in finding a suitable venue. At one point Blin thought of himself for Vladimir, but eventually cast Lucien Raimbourg, an out-of-work cabaret singer and vaudevillian performer, while for Estragon he chose Pierre Latour. Several actors turned down the part of Lucky before Blin persuaded his friend Jean Martin to play it. Blin ended up playing Pozzo himself – despite Beckett’s preference for having an actor who was ‘a mass of flesh’.

From the beginning Beckett would reveal little about the origins of the play. He did admit to having been very struck by Caspar David Friedrich’s painting ‘Two Men Observing the Moon‘. There was speculation that the story was partly inspired by his wartime experiences: the group for which he was working in the French resistance was betrayed, and he and Suzanne had to flee Paris and live in harsh conditions in the village of Rousillon in the rural south, waiting for the war to end. Another possible influence was thought to be his work after the war with the Irish Red Cross in St-Lô in Normandy, where he witnessed much devastation and misery, working among people in desperate need of food and clothing clinging on to life in a ruined landscape.

When Blin asked Beckett about the origin of the word Godot, he said that it was based on the French word meaning heavy boot, godillot, since boots were a feature of the play. Later Beckett enjoyed the confusion caused by the circulation of other versions. One popular one had him asking a group who were watching the Tour de France in the street what they were doing, and receiving the reply ‘Nous attendons Godot’, a reference to a cyclist who had not yet passed. Another, rather less plausible, had him rebuffing a Parisian prostitute on the rue Godot de Mauroy, who then asked: ‘Are you waiting for Godot?’ On the question of whether Godot stood for God, he pointed out that the play was written in French, where the word was Dieu, but admitted that the link could have been in his subconscious.

Blin had rehearsed the play for a year with various actors during the search for a theatre. Beckett sat in on most of the rehearsals, but rarely intervened directly. ‘I have no ideas on the theatre, I know nothing about it,’ he had confessed not long before. Blin kept to his many detailed stage directions, and encouraged the actors to stick close to the text, and not embellish it. ‘I didn’t want to bother the actors with metaphysical notions,’ he recalled. ‘I made them play the basic level, concretely.’ Beckett talked discreetly to Blin at the end of the day, suggesting cuts when a piece of dialogue seemed not to work, and agreeing to small textual changes suggested by the director. Blin sometimes had difficulty in fathoming Beckett’s reaction to their work, often having to rely on surreptitious glances or decoding his cryptic comments. Despite his lack of experience in the theatre, Beckett already had firm ideas about how to stage the play, favouring a stylised rather than a naturalistic type of performance, with a clear separation of speech and movement.

Blin had been struck by the circus element in the play, and the dialogue full of one-liners. He initially thought of staging it in a circus ring, with the actors coming on as clowns. But Beckett opposed the idea, arguing that too much emphasis on this aspect might distract from the play’s seriousness, and that since there were visual references to vaudeville and the work of Chaplin and Keaton and Laurel and Hardy as well as to clowning, it would be too specific. Interestingly in the light of later productions, he made no reference in the text to the characters being tramps. His only demand in relation to their costumes was that all four should wear bowler hats, which gave them the appearance of members of the bourgeoisie down on their luck.

On 3 January 1953, four years after Beckett wrote it, in a converted Paris shop at the end of a cobblestone courtyard at 38 Boulevard Raspail on the Left Bank, with room for just 240 people sitting on folding chairs facing a small, angled stage which had no curtain, Waiting for Godot had its first performance. Word had spread that an unusual play was coming to the Babylone. Although Beckett was still relatively unknown in France, the play had recently been published, as had his novels Molloy and Malone meurt, and an abridged version of the play had been broadcast on the radio. On opening night the theatre was full to overflowing. There was however one significant absentee: Beckett’s horror of such occasions prompted him to leave Paris, and to rely for an account of the performance on Suzanne. This was to become a lifelong habit: ‘I see all my mistakes,’ he said.

The first review in La Libération seemed promising, describing Beckett as ‘one of today’s best playwrights’. But many reviewers were baffled by the play. The most powerful of them, Jean-Jacques Gautier of Le Figaro, chose not to review it, while the writer Gabriel Marcel thought the play was not theatre at all. But Jacques Lemarchand was sympathetic, observing: ‘To arrive at such simplicity and force, one needs an intelligence of the heart and a kind of generosity, without which talent and experience count for little.’ Significantly, two of the most positive comments came from fellow-playwrights: Jean Anouilh compared the occasion in importance to the arrival of Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, describing it as ‘the music-hall sketch of Pascal’s Pensées as played by the Fratellini clowns’, and as ‘a masterpiece that will cause despair for men in general and for playwrights in particular’. Armand Salacrou wrote: ‘We were waiting for this play of our time, with its new tone, its simple and modest language, and its closed circular plot… An author has appeared who has taken us by the hand to lead us into his universe.’

The play inevitably provoked controversy among its audiences, many of whom were shocked by the conversational idiom. One night there was a near riot, with insults flying around and whistles filling the auditorium, so that Blin was forced to lower the curtain before the end of the first act. There was then a confrontation with the hostile members of the audience, who eventually left, allowing the show to continue. On another occasion supporters and protesters came to blows during the interval. The play became a succès de scandale, and the one that it became fashionble to see. It ran for over a hundred performances at the Babylone, with people frequently being turned away. Blin briefly revived it there in the autumn, and then toured it through France, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. After struggling for years to make his name as a novelist, at the age of forty-seven Beckett had suddenly achieved fame – as a playwright.

3 Rehearsals: Week 1

Tuesday 5 July

As Peter begins rehearsing the Shaw play in the large upstairs room of the community centre, the Waiting for Godot company start work in the basement. It’s a fairly tight acting area, with less space in the wings and at the back than the actors will have when they get to Bath. Beckett’s ‘low mound’, on which Estragon sits at the start of the play, is represented for now by a small table. A permanent pillar of the building, though not quite in the right position, stands in for the single tree. At the back of the playing area, as if playing truant from a production of Endgame, is a black plastic dustbin. Sitting at t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Foreword by Peter Hall

- Prologue

- 1 The Readthrough

- 2 Down-and-Outs in Paris

- 3 Rehearsals: Week 1

- 4 1955 and All That

- 5 Rehearsals: Week 2

- 6 The Early Years

- 7 Rehearsals: Week 3

- 8 Prisons and Politics

- 9 Rehearsals: Week 4

- 10 Beckett as Director

- 11 Rehearsals: Week 5

- 12 The Later Years

- 13 The Final Rehearsals

- 14 From Max Wall to the Old Vic

- 15 Finding an Audience

- 16 The Godot Effect

- 17 Summing Up: the Actors, the Critic and the Director

- Sources

- Appendix 1: Letter from Harold Pinter

- Appendix 2: The Bath Company

- Appendix 3: The Godot Company

- Index