![]()

Foreword

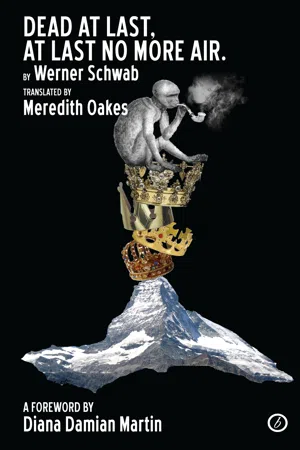

WERNER SCHWAB’S

DEAD AT LAST, AT LAST NO MORE AIR

THE POETICS OF RADICAL DRAMATURGY

DIANA DAMIAN MARTIN

THE FLIPPANT AUTEUR

In Tyranny of Structurelessness, Jo Freeman argues that there is no such thing as a structureless group; as a result, striving for systemic reconstructions is both productive and destructive. Written to address the desire of the US women’s liberation movement in changing, rather than just critiquing society, The Tyranny of Structurelessness introduces a political and philosophical problem in relation to systems. In Dead at Last, At Last No More Air (Endlich Tot, Endlisch Keine Luft Mehr, 1994, Saarländsiches Staatstheater), Werner Schwab takes this argument further: in its current form, a cultural system, he argues, is poisoned, unable to support actual meaning – unsustainable. Despite a constant attempt at formal and theatrical deconstruction, Schwab underpins his rhetoric with a highly political proposition: the theatre has lost its ability to mean, to communicate. This inability is the result of a historically embedded systemic myopism. He re-addresses this through an anti-theatre and a linguistic decomposition that, despite questioning the reasons and implications of this failure, posit the dangers of the imbrication of the political into the theatrical, the domestic into the religious.

In 1999, Austrian right-wing politician Jörg Haider, known for his chameleonic rhetoric and popular opportunism, claimed that Austria must ‘observe the burden of remembrance which must characterise our political behaviour.’ (Haider 2000: np) Ten years earlier, he had argued that Austria underwent an ‘ideological miscarriage’. 1999 was also the year in which he gained 27% of the vote in Austrian national elections, having capitalised on concerns around immigration and EU resentment that led to numerous imposed sanctions on the country as a result of his inclusion in government. Haider foregrounded the irresolvable political and moral tension anchoring Austrian politics and the wider political imagination in the context of a nationalist rhetoric. He launched an attack against the open-border policy of the EU in connection with a national guilt; this carried significant weight within the context of a deliberately confused political rhetoric.

1999 also saw the publication of Hans Thies-Lehmann’s Postdramatic Theatre (not translated into English until 2006), which argued for a re-consideration of the alternative and experimental in the German-language contemporary theatrical landscape in relation to a foregrounding of aesthetics in relation to space/time, body and text. Lehmann’s study quickly became a key surveyor of the landscape in which Schwab’s theatrical discourse is positioned. His dramaturgy was thus framed by the concerns of a postmodern intellectual climate and what the author perceived to be a stifling, bourgeois, institutionalised theatre culture; yet the formal and political resonances of his work, and the strategies developed throughout his practice, echo beyond the specificity of an Austrian political imagination. It’s no surprise that his plays, characterised by linguistic deconstruction and composition, structured fragmentation, violent and grotesque poetics and a constant destruction of dichotomies, divorce communication from its usual tropes in order to reach a different form of intellectual transgression.

Schwab never got to see the publishing of Lehmann’s book, or, perhaps more significantly, Haider’s public prominence. In 1994, Schwab died in his apartment in Graz on New Year’s Day after an excessive drinking spree at the age of thirty-five. During his brief theatrical lifetime, he authored sixteen plays, five of which were published after his death. These appeared in three volumes: Fäkaliendramen (Faecal Dramas), Königskomödien (Comedies of Kings) and Dramen. Band III. It’s no accident that Dead at Last, At Last No More Air, his last play (aside from those published posthumously) weaves together the tense political landscape that was taking shape in Austria at the time, with a particular resentment towards an institutionalised theatrical formalism. If Haider’s rhetoric sounds familiar to a contemporary British political climate, then it’s important to underline that in Schwab, it’s not humanity that has failed, but a cultural system so embedded and intertwined with a problematic domestic and political conservatism. In Dead At Last, At Last No More Air, Schwab raises questions about the systemic failure of theatre to express any meaning. Thus in this Foreword, I will discuss key influences and contexts that have shaped Schwab’s work, with particular focus on Dead At Last, At Last No More Air.

The play takes place within a non-specific theatre, in which cast and creatives are attempting to put on a play. Director Saftmann is attempting to put on Mühlstein’s play, but finds no truth in it. Their confrontation results in Saftmann dismissing the playwright and actors, and inviting in a group of pensioners and a homeless man from a nearby senior home. They sabotage the production and overthrow Saftmann. In the end, the cleaner, Frau Haider, is crowned leader. Beginning with a play-within-a-play and ending with its collapse, Dead At Last, At Last No More Air is, in Schwab’s words, a theatre-extinction-comedy. It moves between the theatre, as isolated, constructed realm and the interruption of a social, political reality, that also crumbles when entering the theatre itself. Schwab thus makes an explicit connection between theatrical meaning, the state and the failure of language to communicate; meaning here is beyond repair. His key strategy is to place elements such as violence, sex, death, scatology in confrontation with an ideological landscape and social critique, proposing the death of theatre in the face of such corruption of meaning and form.

The character of Frau Haider, the cleaner who is elected leader of the coup d’état undertaken by the dispossessed and marginal within the walls of the theatre, wearing a crown from an old Shakespeare production of Richard III, announces at the end of the play: ‘the world all told is a disappointment, because the world, which always wants to tell the world what the world has to be, has been lost. I shall put everything right.[…] My body has eternal victory built in.’ (Schwab/Oakes 2014: 51) The embodiment of victory paves the way for a re-inscription of values of the ‘world above’. As is the case with previous Schwab plays, most notably, Die Präsidentinnen (1990, Künslerhaus Wien) and Volksvernichtung oder Meine Leber ist sinnlos (1991, Münchner Kammerspiele), Frau Haider is based on Schwab’s mother, a cleaner herself, and politician Haider. The interweaving of the political and the domestic, the personal and the public is typical of Schwab’s performative strategies. On the other hand, director Saftmann fails in his attempt to rejuvenate theatre by bringing it closer to the communal reality; yet the failure is more complexly situated in the dynamic between Schwab’s different elements.

The author links two dichotomies together: the inner and the outer in the theatrical paradigm and the individual and society in the political realm. This results, particularly in Dead at Last, At Last No More Air, in a dismantling of these very dichotomies; the real world and the theatrical world are, in Schwab, one. Typical of Schwab’s work, erasure, order and violence compete in the careful non-dramatic construction of a contemporary that is fragmented, in tension with a disputed history – in this case, Austria’s relationship with its past.

There is a strong element of flippancy that Schwab’s work engages with, also appropriated by the author in the treatment of his own success. In his short career, Schwab experienced a high level of praise within the German theatre world; even in their initial incarnations, his plays were put on at major theatres in Austria, Germany and Switzerland, in particular Vienna, München, Stuttgart, Hamburg, Zürich and his own birth place, Graz. Beate Hochholdinger-Reiterer argues that this sudden success originates in German receptions of his work, picked up by Hans Gratzer’s second tenure at Viennese Schauspielhaus in 1991, who opened the season with Übergewicht, unwichtig: Unform (Overweight, unimportant: misshape). The opening was followed fairly quickly by Volksvernichtung oder meine Leber ist sinnlos (People-Annihilation or My Liver is Sensless) at the Münchner Kammerspiele the same year. Schwab’s success went hand in hand with a particular identity politics in his own writing. Mühlstein, for example, is the self-mocking playwright that challenges his own profession and meaning in the theatre – a strong self-identification from Schwab. Flippancy manifests itself in Schwab as the strategy through which, as public persona, he plays with expectations, as well as a writer who mocks himself, his own characters and context. Schwab’s most infamous plays are fiercely and darkly humorous, with a politics that is at times, deliberately malleable and theatrically opportunist. Schwab purposefully presented himself as an enfant terrible of Austrian theatre, enjoying a different public life than his contemporaries Peter Handke, Elfriede Jelinek or Rainald Goetz. Referring to himself as Project Schwab, citing Derrida and Baudrillard, the author ascribed his own success to a particularly German attitude towards the rebellious public intellectual. Schwab claimed that this enabled him to use the term ‘“The Blond Giant” once again.’ He adds, ‘if I were bespectacled, I would lose at least one third of my success.’ (Hochholdinger-Reiterer 2002: 301)

The elements of autobiography found in Schwab, viewed alongside his public persona, pose a challenge to the interpretation, adaptation, translation and staging of his work. Just when intent becomes clear in his work, it is subverted by flippancy and performativity. Schwab’s plays are imbued with explicit and self-mocking critique, both thematic and formal. Thus when identifying his critical engagement with strong thematic elements to his dramaturgy – such as the family order, the conservative state and the church – one has to be careful towards a solely Austrian identification. These are not isolated problems, Schwab argues, but make visible a wider European concern. As a result, Schwab makes for an intriguing, if not subversive canonical figure. Through both work and public appearance, Schwab posits a problem of responsibility fuelled by growing cultural and political concerns.

CULTURAL TERRITORIES

‘What air this is here. It’s an air that doesn’t care if it’s breathed.’

Despite his success, theatre scholars have been reluctant to ascribe the term ‘popular’ to Schwab’s work, underlining his emphasis on destruction as a transgressive process.1 In Dead at Last, At Last No More Air, destruction acts as a key performative principle, underpinning the narrative of the play, but also the ways in which description, action, language and character begin to fragment and blend into each other. Schwab is thus more productively understood as engaging with tropes that dominate perceptions of culture – high and low, popular and esoteric. There is a complexity to his theatrical argumentation and fragmentation, that results in a disabling of these tropes through the interaction between language and form.

Schwab trained as a sculptor before entering the world of the theatre. As his biographer Helmut Schödel emphasises, despite his autodidacticism, Schwab held a wide knowledge of twentieth-century theatrical tradition, appropriated with particular profundity and insight. Despite an overt dismissal of theatre’s bourgeois values, Schwab’s knowledge ranged from the work of Samuel Beckett to that of Oswald Wiener and Thomas Bernhardt. To some extent, Derrida enabled Schwab to take a deconstructive approach in his linguistic compositions. For Derrida, meaning is complicated by the absence of finality and, occasionally, intelligibility, ‘a madness of the impossible’. (Derrida 2001: 55) For Schwab, the philosopher’s denial of the absence of an outside of the text implicates a deliberately problematic ambiguity of meaning. Thus Schwab developed a politics of meaning particular to his dramatic pathology. His dramaturgy is both specific in its references, constructs and dramatic scaffolding and deconstructive of those textual processes; nothing is allowed to remain fixed or static.

The other philosopher who influenced Schwab was Baudrillard, who argued that meaning emerges as a result of a complex web of interrelated semiotic structures. Asserting meaning as deriving out of negative processes, out of something that cannot be, Baudrillard further developed the poststructuralist idea of meaning as relative. The very beginning section of Dead at Last, At Last No More Air holds an implicit reference to Baudrillard:

To whom does language belong?

Language belongs to the thing one might call DIRT. DIRT discovered language, when the thing one might call BEAUTY defencelessly declared a war without any objective.

Whereupon ONE OF THEM lost the war of wars.

We know: WHICH ONE.

From that time, people began: communicating to each other what has to be the most total flawed goods: COMMUNICATION!

(Schwab/Oakes 2013:1)

On the one hand, communication’s impossibility exists in the realm of the hyperreal2 – a composition of references with no origin, no referent. On the other, the real extends into the realm of the fictional, and the fictional becomes the real. History, both artistic and political, is no longer situated, distanced from the present – it is embedded in the contemporary. It’s no surprise that in Dead At Last, At Last No More Air, Herr Adolf is a homeless man, spending his time with pensioners who are bidding for sex with him, in a former theatre.

Hans Thies-Lehmann’s Postdramatic Theatre provided a rich theoretical lens through which to analyse a generation of playwrights that Schwab was very much part of, from Jelinek to Müller. As Karen Jürs-Munby argues in the Introduction to Lehmann’s English translation, much of the scholar’s project sought to address the crisis of drama identified in theatrical registers that sought to recall the real onstage, reconciling ‘beauty and ethics’(Jürs-Munby in Lehmann 2006: 5). For Lehmann, the theatre is the site where ‘a unique intersection of aesthetically organised and everyday real life takes place’ (Lehmann 2006: 17); it is also the place in which text becomes re-contextualised, battling the visual, audible, gestural and architectural fields. Capitalising on the impact of media, as well as Performance and Live Art of the Sixties and Seventies into the registers of theatre and performance, Lehmann argues that distinct to postdramatic theatre is the move away from the internal logic of a story’s progression.

In Dead at Last, At Last No More Air, Schwab addresses this seemingly perverse exercise in his play-within-a-play; Mühlstein’s constant interest in representation as authentic, melodramatic love is ironically undercut by director Saftmann’s search for a clinical authenticity. Therefore Schwab’s work pertains to particular aspects of the postdramatic: in his relationship and foregrounding of composition, both formal and linguistic, as well as his emphasis on the body as carrier and locus for meaning-making. Schwab’s awareness of the dynamic relationship between his public persona and his dramaturgy, between the external and the internal, results in a collapsing of and flirtation with irony. His work is self-critiquing, referential and destructive towards itself. His attitude towards institutionalised theatre is most visible in its use of the play-within-a-...