![]()

SCENE 1

PERFORMER and OPERATOR play a computer game like ‘Call of Duty’ as audience enters. The game is projected onto the small screen. Background texture is on the gauze. PERFORMER presses ‘pause’ on his controller and the video pauses. PERFORMER turns to face the audience and then picks up his phone.

PERFORMER via WhatsApp (each paragraph reprints a message):

“Hi.”

“Thanks for coming.”

“Don’t worry, I’ll be talking to you soon.”

“I’m sure you’ve used something like this before. WhatsApp, or Facebook messenger maybe. Maybe to organise a stag or a hen do. A birthday party or.

A holiday or something. It’s a really useful tool. You can broadcast to loads of people at once. And. Even though this is less relivant to planning your Aunty’s 50th.”

“FFS”

“RELEVANT”

“It uses peer 2 peer encryption. So unless someone’s phone is hacked, the only people who can read our messages are us in this room. Which is why some governments don’t like it. Anyway.”

“For some of this show I’ll talk to you via this, so please leave your phone on. And if you notice someone without access to a phone, maybe share your screen with them.”

PERFORMER talks directly to the audience, using the following bullet points as a guide:

• I love instant messaging

I love instant messaging to be honest. Especially when it’s encrypted.

• It puts you in constant touch with people

I have mates, especially cultural types; artists, academics and journalists, who I am in constant touch with on stuff like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. Some of them I’ve never met in the flesh, but they feel closer to me than some people I ‘know’ know.

• You can upend stereotypes

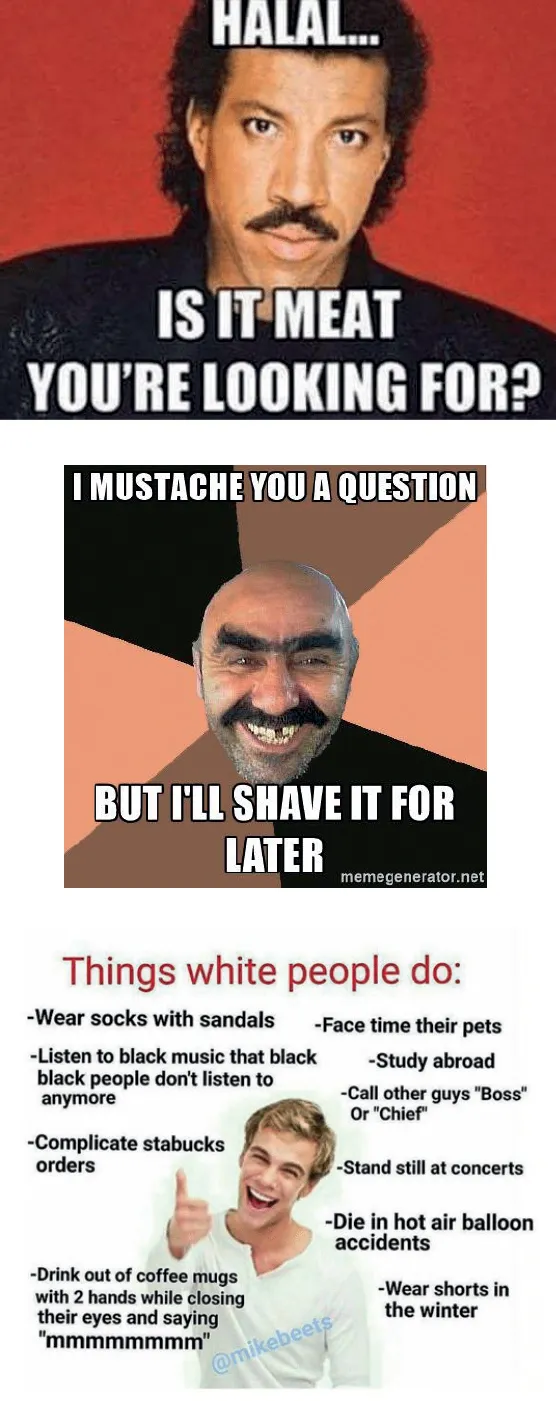

They keep me up to date on global politics and because a lot of us are of Asian or Muslim origin and these channels are private, we can have a certain kind of banter about stereotypes of us, the jihadi, drug dealer, pimp, sex offender stereotypes. And we can make up our own to throw back.

Send memes

Performer to audience via WhatsApp:

• There are funny and cute memes too

And there’s those cute memes too, stuff like Doge and Lolcatz, which you know you shouldn’t laugh at but you always do.

Performer sends some examples of memes via WhatsApp:

• What the show is about

This show isn’t about instant messaging and my love of memes. That would probably be much more entertaining for me than it would be for you. It’s about men, the internet and politics.

Some of the show will happen on WhatsApp. And some of it I’ll tell you through this screen, because it needs a certain kind of distance.

![]()

SCENE 2

PERFORMER is mediated digitally in some way, perhaps through Skype connection.

PERFORMER: It’s the distance that connects you to a voice you don’t trust in the middle

of the night. You followed the chain of links and now you find yourself alone with me.

This story starts in a cell. This is the story of how the West’s colonial nightmares of Islam came to be seen on a million digital screens. It’s a vision made vision made flesh.

This cell could be anywhere, but it isn’t. From the uniforms on the prison guards, the heat, and the way the inmates speak Arabic, we know that this is a cell in Egypt. 1957.

A thin man shakes. On the edge of the desert he lives a rhythm. Hunger. No sleep. Little Water. Work. Interrogation. Torture. His large, sad eyes seem even bigger, and his naturally fat cheeks hang. One percussive thud and the door to his cell is opened. The acrid midday sun cuts the room in two. Three men enter. Methodically and medically they cut his prison clothes away and smear his body in animal fat. Outside the door, there’s barking, growling. The door is closed and dogs let off their leash. The man loses consciousness around the time he suffers his third heart attack.

In that baking hot cell, in that pain and tortured train of semi-conscious thought, Seyyed Qutb, the intellectual father of modern jihadism, has a series of visions that bring together the past twenty years of his thought. As his heart arrests, he sees a world dividing and the cosmic choosing of sides. The battles between early Muslims and the Arab aristocracy are not something in the past but battles that eternally return, more bloody and catastrophic every time. There is only one small group of believers and they are his followers. Everyone else is a slave of ignorance and a servant of darkness. This is a vision of truth, and love, freedom and utopia that can only be reached by climbing a mountain of corpses.

![]()

SCENE 3

PERFORMER speaks directly to the audience, using the following bullet points as a guide:

• But this is my story too

But this is my story too.

Projections from digital screens fill the space; YouTube videos, news footage, images that speak to the stereotypes of Muslims.

A story that plays out every day. Like every other Muslim in this country, I see a news story that makes me the subject of a narrative I don’t recognise, a conversation about me that I’m not part of.

• Social media is where everybody has a voice

Social media is where everyone gets a voice, so let’s do this next bit on WhatsApp.

• WhatsApp quiz

PERFORMER interacts with the audience via WhatsApp, asking the audience questions and waiting for replies, for example:

How many Muslims live in this country?

Any guesses?

How many have joined ISIS?

• The answers

There are around 3 million Muslims in this country and only 300 have joined ISIS. That’s less than one one thousandth of one percent.

• Conversations

We can have a conversation on WhatsApp that we couldn’t have anywhere else.

• You can speak without cutting each other off

We can speak together without cutting each other off.

• It’s anonymous / democratic / right or wrong

Everyone is sort of anonymous, so you can just say what you want. It doesn’t matter if you’re wrong, you can get your views out. It’s democratic. Your opinions are disconnected from your identity.

• Not individual / anyone can talk, anything can be said

You’re not an individual, you’re a group.

It doesn’t matter how good looking you are, how clever you are, or how expensive your shoes are. It’s a p...