![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Specters of Saint-Domingue

IN THE MID-1790s, Philadelphia, capital of a nation recently born of revolution, was teeming with exiles driven from their homes by a cycle of revolution sweeping the Atlantic world. Some came from France, victims of one or another political purge. But many more had come from the Caribbean, particularly Saint-Domingue, fleeing slave revolution. There were white masters and merchants, previously rich and now reduced to dependence on former trading partners or charity. There were free people of color whose presence in Philadelphia became the subject of some controversy. And there were many slaves, brought as property from colonies where slavery no longer existed, treated as property in a city where the institution was only slowly being extinguished.

Among these exiles was a man named Médéric-Louis-Elie Moreau de St. Méry, a lawyer, writer, and onetime resident of Saint-Domingue. Like many exiles, he had arrived carrying almost nothing. He was in fact lucky to be alive: a warrant for his arrest had been issued in Paris just as he escaped the port of Le Havre in 1793. In his haste he had left behind an irreplaceable possession: a set of boxes filled with notes and documents he had collected over a decade of research for books he was writing on French Saint-Domingue and Spanish Santo Domingo. Friends promised to send the essential notes after him. But in the midst of war and revolution there was little certainty. Would the boxes find him? Had they been burned as fuel on a ship or thrown overboard for want of room? Had they sunk to the bottom of the sea during a storm or an attack? By great good fortune, the boxes reached Moreau in Philadelphia. “It is one of the joys in life I savored the most,” he wrote. He at once resumed working on a book that had been near completion when, as he put it, the revolution “made me powerless to accomplish my project.”1

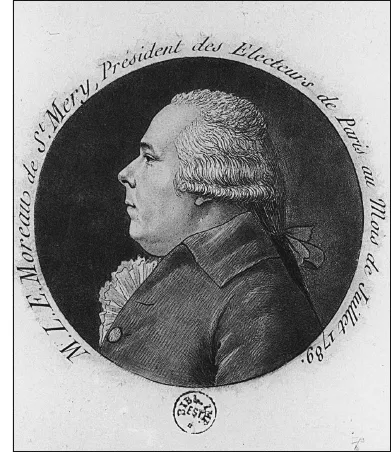

An engraving of Moreau de St. Méry done in Paris, 1789. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Moreau was a citizen of the Atlantic. Born of an important creole family in Martinique in 1750, he left for Paris at nineteen to study law. He received his degree two years later and took up a prestigious position at the Paris Parlement, the most important court in the nation. In 1774 he suddenly resigned and left for the Caribbean, where he settled in Saint-Domingue. He established himself as a lawyer, married into a well-connected family in 1781, and gradually became an important figure. Moreau was also a freemason, and in one of the lodges of Le Cap, of which he later became president, he rubbed elbows with many of the leading men of the colony.

Through his work as a lawyer in Saint-Domingue, Moreau became irritated about something he would harp on for most of the rest of his life: no one, especially the administrators on both sides of the Atlantic who governed the Caribbean colonies, knew anything about them. He decided to try to solve the problem, and, working with other members of a local scientific society called the Cercle des Philadelphes, he began to gather information on Saint-Domingue’s law, history, environment, and economy. It was a classic Enlightenment project, based on the idea that knowledge would promote better governance. Because many of the archives he needed to consult were in Paris, he returned there in 1783. The Colonial Ministry provided him with an allowance and access to its archives. In 1784 he published the first part of what became a six-volume history of colonial legislation. He returned to Saint-Domingue, where he continued his research and his struggles with the royal administration. In 1788 he again left the colony for Paris. He was poised to produce his Description of the Spanish and French colonies when the French Revolution began. Moreau quickly became active in politics. He was chosen as the president of the electors of the city of Paris and participated in the raging debates about colonial policy. Meanwhile his project languished. There was little time to write history as he tried to survive it. Like many political moderates, he ended on the wrong side during the Jacobin Terror and had to flee for his life.2

He ended up in Philadelphia and returned to his writing. He published a Description of Spanish Santo Domingo in 1796, but faced a peculiar problem with regard to the French colony: in the years he had been away from it, much of what he had known there had been destroyed or irrevocably transformed by revolution. Moreau worried that the story of Saint-Domingue, the “most brilliant” of the colonies of the Antilles, might be forgotten if he “did not hurry to offer a truthful portrait of its past splendor.” At the same time, he imagined “a crowd of people” accusing him of doing “useless work or hoping to excite regrets for which there was no longer any remedy.”3

But it was worth telling the story of Saint-Domingue, Moreau insisted. If there was to be a reconstruction of the colony, as he firmly hoped, it would have to be based on knowledge of what the ruined plantations and towns had once been, and an understanding of how the colony had functioned, and why things had ultimately gone so wrong. It was possible, Moreau believed, to make the colony once again “a source of riches and power for France. In these fields still smoking with blood and carnage, we must bring back abundance.”4

In its “short existence,” Moreau wrote, Saint-Domingue was “a colony whose nature, splendor, and destruction” were unique in “the annals of the world,” and a part of the “History of Nations,” like the great civilizations of Greece and Italy. His book, Moreau hoped, might encourage people to “meditate on Saint-Domingue,” and to draw as much from this act of contemplation as they would from looking at the “debris of Herculaneum.” A century and a half later, another Martinican, Aimé Césaire, would similarly insist that “to study Saint-Domingue is to study one of the origins, one of the sources, of contemporary Western civilization.” Both writers insisted that rather than being seen as a place on the margins of Europe and its development, Saint-Domingue must be seen as central to this history.5

Curiously, Moreau shied away from one aspect of Saint-Domingue’s history. “Has the time come to write on the colonial revolution? . . . I think not.” That was why his book, as he announced, represented Saint-Domingue as it was “on the first day the revolution appeared there.”6 And it was why “1789” was repeated throughout the text, often simply as “this year.” Like many exiles, Moreau sought to return home by writing about it. That home had been completely transformed by slave revolution, and his work was a walking tour of a vanished world. But, harboring hope that the colonial world might be rebuilt, the exile was also calling up specters of the past in an effort to exorcise the present. In the process he left a remarkable snapshot of the brilliant and brutal colony of Saint-Domingue.

“One good white is dead. The bad ones are still here.” This, Moreau wrote, was what the blacks of Le Cap heard in the melody of the funeral bells of the church. It was, perhaps, a subtle way of saying that the only good white was a dead one. Each time the bells rang, another corpse joined the generations of the dead haunting Saint-Domingue. The colony was a graveyard for its original inhabitants, decimated by Spanish colonizers; for its European settlers and soldiers, who succumbed in large numbers to fevers; and of course for the many slaves who died there from execution, overwork, sorrow, or (though rarely) the weight of years.7

The dead were divided as the living were. Some whites—individuals of importance in the colony, or those rich enough to pay the 3,000-livre charge for this honor—were still buried near the church, in a single tomb built for the purpose. (In France they would have been placed under the church itself, but this practice had been given up in the heat of the tropics to spare worshipers from the stench of rotting corpses under their feet.) In the tomb were the bodies of two governors of the colony, as well as the bones of the Jesuits who had died there during the first half of the eighteenth century. When Moreau visited in 1777, he noticed some bones sticking out of the ground in the tomb, but doubted what some said about them—that they were the remains of those Jesuits, miraculously preserved.8

The church graveyard was small, however, and most whites were buried in a cemetery at La Fossette, on the outskirts of Le Cap. La Fossette had first been used as an overflow cemetery during an epidemic in 1736, receiving the bodies of two ill-respected groups: blacks and sailors. A few decades later, with the cemetery surrounding the Le Cap church too full, it became the official town cemetery. La Fossette—originally called L’Afrique by the Company of the Indies when it occupied the area as part of its slave-trading operations—also had a cemetery for non-Christians. Unbaptized African slaves—called bossales—who had died soon after their arrival were buried around the “Croix bossale.” (The 1685 Code Noir, which governed the treatment of slaves in the French colonies, stipulated that unbaptized slaves be buried “at night in a field near the place where they died.”) It was perhaps these graves that brought slaves to the area for “dances” on Sundays and holidays. Outside the second-largest town in the colony, Port-au-Prince, African slaves were buried in a swampy site also called “Croix bossale.” Animals, however, often disinterred the corpses. Local officials, worried about the “exhalations” through which the “dead seemed to menace the living and punish them for their disregard for humanity and morality,” established a better-placed cemetery for slaves.9

Throughout Saint-Domingue the enslaved often created their own cemeteries by taking over those no longer used by whites. In one town in the Northern Province an abandoned cemetery was still “recognized by the superstitious veneration of the negroes.” In the parish of Aquin, in the south, slaves buried their dead near the ruins of the chapel on the site of an early settlement. Attempts to force them to use the official cemetery failed; the slaves just waited until night to bury their dead. So the bodies of those once enslaved were buried alongside the bodies of those once free. Elsewhere the dead of both groups were united for other reasons. Moreau noted with disgust that in one small town “white and homme de couleur, and free and slave” were all buried together because there was no tradition of registering the burials. In another, little-populated part of the colony a small cemetery, marked by a cross, indiscriminately welcomed the bodies of “the whites and negroes.” Natural forces sometimes also brought the dead together. In 1787 a ravine overflowed during a powerful tropical storm, drowning two slaves, sweeping away carriages and furniture, exhuming the corpses from a small cemetery, and carrying them into the ocean—itself a giant cemetery for those Africans who had not survived the middle passage.10

The dead were inescapable in Saint-Domingue, as Moreau lamented in describing the entrance to one town where the sight of a pleasant fountain was offset by the cemetery beside it. It was as if a vow had been taken always to strike travelers with the “lugubrious” presence of the departed. At the same time, Saint-Domingue was a powerful life-source for the booming Atlantic economy, generating fortunes for individuals on both sides of the ocean. Its plains were covered with sugarcane cultivated on well-ordered and technologically sophisticated plantations, supported by efficient irrigation works. The mountains were full of burgeoning coffee plantations, and the towns bustled with arriving and departing ships, passengers, and goods of all kinds. Within a century it had grown from a marginal Caribbean frontier into the most valuable colony in the world. In the process it had welcomed a bewildering mix of people—Gascons, Bretons, Provençals from France; Ibo, Wolof, Bambara, and Kongolese from Africa. On the verge of a revolution, it was a land of striking contrasts.11

Christopher Columbus landed on the island during his first voyage, in 1492. The indigenous Taino seem to have called it Ayiti, but Columbus gave it a new name: La Española. On the northwest coast of the island, Columbus left behind a small group of sailors in the care of a local Taino chief. He returned the following year to find the settlement abandoned and destroyed, with most of those he had left behind buried nearby. The chief he had entrusted with his men claimed that a group of Caribs from another island had attacked and he had been powerless to defend the Spaniards. It is more likely that (not for the last time) the initial peace between Europeans and the indigenous peoples had devolved into violence.12

This first European settlement in the Americas had failed, but more followed, and quickly. Española—or Hispaniola, as it came to be known in the Anglophone world—was the ground zero of European colonialism in the Americas. The brutal massacre and bewildering decimation of indigenous people that took place there would be repeated again and again in the following centuries, though rarely with the same startling speed. Under the encomienda system, settlers were granted the right to the labor of indigenous people in order to mine for precious metals. It was not technically slavery—workers were not owned by the settlers—but in practice it was little different. Overworked, attacked by diseases against which they had no immunity, executed as punishment for revolt, and often committing suicide to escape their brutal conditions, the indigenous population declined precipitously within the first few decades of Spanish colonization. By 1514, of a population estimated to have been between 500,000 and 750,000 in 1492, only 29,000 were left. By the mid-sixteenth century the indigenous population of the island had all but vanished.13

The “devastation of the Indies” was chronicled by Bartolomé de Las Casas, who arrived in Hispaniola as a young settler in 1502, and was transformed by what he saw. Within a decade he became the first priest ordained in the Americas, and a harsh critic of the brutal treatment of the Taino by the Spaniards. He decried those who justified Spanish brutality as a necessary response to the barbarism and violence of the natives: “our work was to exasperate, ravage, kill, mangle and destroy; small wonder, then, if they tried to kill one of us now and then.” He documented horrifying acts of violence meant to terrorize the population. “It was a general rule among the Spaniards to be cruel; not just cruel, but extraordinarily cruel so that harsh and bitter treatment would prevent Indians from daring to think of themselves as human beings or having a minute to think at all.”14

In Moreau’s Saint-Domingue there were many reminders of this history. Workers building a canal on a plantation in Limonade discovered, along with several Spanish coins, the bodies of twenty-five Spaniards who had been buried in a traditional Taino manner. They were, Moreau believed, the corpses of those left behind by Columbus in 1492. And the anchor found buried in the dirt on a plantation near the ocean was, he wrote, that of Columbus’ Santa Maria, which had sunk off the coast of the island in 1492. Elsewhere there was forensic proof of Spanish cruelties. In a cave in the north of the colony were found five skulls with their foreheads flattened—a common practice among the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean—which identified them as “Indian.” No other bones were found, however, and Moreau concluded that this was because the “Spanish had dogs to whom they gave over the corpses of their unfortunate victims.” He knew his history well: in 1493 Columbus had indeed brought attack dogs—mastiffs and greyhounds—to terrorize the Taino population.15

The colony was in fact full of haunting reminders of its vanished inhabitants. In Limonade one encountered “with each step, debris of the utensils of the indigenous peo...