![]()

The Sayings and Stories

. . . . . . .

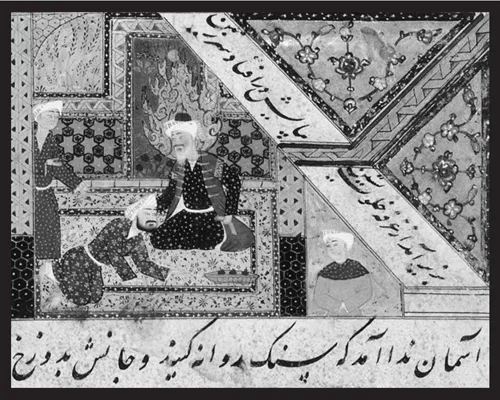

Jesus and the Pharisees. On of the seventy-two miniatures illustrating the book

Kulliyat, by the Persian poet Sa

di (British Library MS.Add.24944). Shiraz/ Safavid,

A.H. 974,

A.D. 1566. Jesus is seated in the center, haloed in flames, while a Pharisee is seen flinging himself at a plate of food. The sayings and stories contain many condemnations of the gluttony and greed that allegedly typify scholars of the law. Reproduced by permission of the British Library.

A WORD ON THE COMMENTARIES

In general, I have selected the earliest version of each saying or story, but I have also appended references to citations in later sources, in approximate chronological order. In addition, I provide references to three major collections of these sayings:

Miguel Asin y Palacios, “Logia et agrapha domini Jesu apud moslemicos scriptores, asceticos praesertim, usitata,” Patrologia Orientalis, 13 (1919), 335–431; and 19 (1926), 531–624.

Hanna Mansur, “Aqwal al-Sayyid al-Masih

ind al-kuttab al-muslimin al-aqdamin” [The Sayings of Christ in Ancient Muslim Writers],

Al-Masarra (1976), 45–51, 115–122, 231–239, 356–364; ibid. (1977), 107–113; ibid. (1978), 45–53, 119–123, 221–225, 343–346, 427–432, 525–528, 608–611.

James Robson, Christ in Islam (London: Allen and Unwin, 1929).

The abbreviation EI 2 refers to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, new edition, ed. H. A. R. Gibb et al. (Leiden: Brill, 1960–).

Where editions or texts are defective, I have tried to indicate this in the references or commentaries.

In formulations of dates—e.g., “131/748” or “first/seventh century”—the number preceding the slash refers to the Islamic calendar (anno hegirae, or A.H.), while the number following the slash refers to the Christian calendar (anno domini, or A.D.).

I have kept the commentaries as brief as possible, attempting first of all to place the sayings in their Islamic context and to ask how their Muslim audience might have received them. But I have also tried where possible to suggest parallels to them in the Gospels, the Apocrypha, and other literatures of the Near East and beyond. In a few cases, I appended no comments at all where I judged none were needed. Where my readers recognize an origin for any of these sayings, I would hope that this might enhance their interest in the corpus as a whole.

The commentaries that Asin appended to his collection are in Latin and therefore of limited access. This is regrettable because many of his comments are still of great value; I have referred the reader to them in several places.

There are five sayings whose Arabic originals I have not been able to trace. I have given the references to them as cited by Asin.

1 Jesus saw a person committing theft. Jesus asked, “Did you commit theft?” The man answered, “Never! I swear by Him than whom there is none worthier of worship.” Jesus said, “I believe God and falsify my eye.”

Hammam ibn Munabbih (d. 131/748),

Sahifat Hammam ibn Munabbih, p. 34 (no. 41). Cf. Muslim,

Sahih, 7:97; al-Turtushi,

Siraj al-Muluk, p. 434; Ibn al-Salah,

Fatawa wa Masail ibn al-Salah, 1:181–182; Majlisi,

Bihar al-Anwar, 14:702 (variant); (Asin, p. 579, no. 184; Mansur, no. 208; Robson, p. 59).

Hammam ibn Munabbih was the brother of Wahb, the celebrated and semi-legendary authority on pre-Islamic antiquities. The Hadith collection from which this story of Jesus was taken is claimed by its modern editor to be the oldest surviving collection of Hadith; see the introduction to the collection, cited in the Bibliography. If the editor’s views are accepted, this would mean that stories about Jesus circulated in Muslim circles as early as the first/ seventh century.

The story seems to suggest the primacy of faith, which overrides any sin, even those committed in flagrante. It may also suggest abstention from judgment, in order perhaps to preserve social peace, thus giving the sinner the benefit of the doubt. The story may well have political implications: rulers should be left to God’s judgment even if they are manifest sinners.

2 Jesus said, “Blessed is he who guards his tongue, whose house is sufficient for his needs, and who weeps for his sins.”

Abdallah ibn al-Mubarak (d. 181/797), Kitab al-Zuhd wa al-Raqaiq, pp. 40–41 (no. 124). Cf. Ibn Abi al-Dunya, Kitab al-Samt wa Adab al-Lisan, pp. 189–190 (no. 15); Ibn Hanbal, Kitab al-Zuhd, p. 229 (no. 850) (Abdallah b. Umar instead of Jesus); al-Qushayri, al-Risala, p. 68 (the Prophet Muhammad instead of Jesus); Ibn Asakir, Sirat, p. 151, no. 158; and al-Zabidi, Ithaf al-Sada al-Muttaqin, 7:456

(slight rearrangement of order) (Asin, p. 597, no. 217; Mansur, no. 254; Robson, p. 61).

Abdallah ibn al-Mubarak was a well-known Hadith scholar who took a special interest in ascetic traditions. On his life and works, including the manuscript problems of the work from which these Jesus sayings are taken, see the...