![]()

— 1 —

The Big Picture

The Great Barrier Reef, Nature’s pinnacle of achievement in the ocean realm, is the embodiment of wilderness, of remoteness—a place of endless beauty that has endured when so many other places on Earth, cherished by generations past, no longer engender strong emotions or else have been altered beyond all recognition. A truly cohesive account of how the Great Barrier Reef has changed in the geological past and will change in the human-controlled future must embrace concepts of time, the linking of disparate scientific disciplines, and the human takeover of climate control. As we turn from past to future in this book, we delve into scientific advances that are still in their infancy and that often go unappreciated because they are viewed in isolation rather than as part of a bigger picture.

What an extraordinary experience it must have been for the pioneering astronauts to have seen the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) from space. When they first looked down on the blue planet, the GBR was readily recognizable, for it is the largest construction of living organisms anywhere on Earth. Unfortunately, not many of us are privileged to see it from this vantage point. Even a bird’s-eye view of the GBR during surveys using long-range aircraft cannot convey the same sense of size. As the plane flies on, hour after hour, the senses become overloaded, and when we review the flight path afterward we are always reminded that we saw just a fraction of the GBR’s total area.

Diving on the reef is a completely different matter, for reefs create feelings of limitless size, unlike anything on land. Only the best movie photographers can capture the ambience of truly pristine reefs surrounded by a profusion of animal life: corals, fish, anemones, urchins, starfish, shellfish, and small creatures everywhere—a diversity rarely seen on land, not even in rainforests. Then there are the vertical cliff faces and the ceilings of caverns, all ablaze with the color of filter feeders: ascidians, sponges, sea fans, crinoids, and nonreef hard and soft corals. A healthy reef has an amazing wealth of life, most of it still beyond the knowledge of science.

Diving at night is to enter yet another world, for the diver’s light reveals tiny animals by the thousands: clouds of plankton of all shapes, sizes, and colors, swimming frantically, lured by the light. Corals, opening their tentacles to catch these frenetic little swimmers, transform themselves into beautiful anemone-like creatures, quite different from their daytime guises. At night large predators move through the distant darkness: sharks that roam unceasingly, in the hundreds, around all the great reefs of the world—at least those few remaining reefs where these sleek marauders have not yet been decimated. Day and night, corals are home to thousands of smaller animals that live within the protection of their stony branches.

Good photographs sometimes capture these scenes, but they can never convey the emotions of those of us fortunate enough to have actually looked upon this world. The greatest reefs of the GBR instill awe and wonder—but also fear, especially the less well-known reefs in the remote far north. The sight of large animals—whale sharks, manta rays, giant groupers, big oceangoing silver fish, and even the occasional whale—never fails to thrill, and all such sightings are added to the already prodigious collection of tales, to be retold (usually with embellishments) by the thousands of divers who have explored the reef.

Then there is the ever-present threat of depth, for clear-water reefs that plunge down into deep ocean can be deceptive, and all too often become a fatal attraction for an enthusiastic diver who wants to get just a little more out of the trip of a lifetime.

Electronic navigation and satellite imagery have virtually put an end to the GBR’s long-held reputation of being one of the world’s most dangerous places for ships. Today tropical cyclones are more feared than reefs, but there was a time when the GBR had more shipwrecks than the rest of Australia combined. A glance at any chart shows why, for within it reefs of all sizes—hiding just below the surface and enveloped by strong tidal currents—form a maze of many thousands of square kilometers.

Although I have worked on all the major reef regions of the world, most of the exceptionable dives of my life have been somewhere on the GBR. Of the truly great places on our planet that those first astronauts looked down upon, the GBR is surely one.

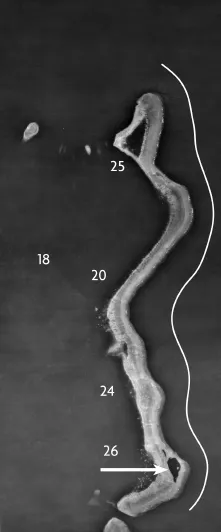

A Special Place: Tijou Reef

Tijou Reef, in the northern GBR, illustrates topics that arise in several of the following chapters. I remember my first dive down its outer face; as far as I know, it was the first time anyone had dived down the outer face of any ribbon reef. We made the dive specifically to see how close the Queensland Trough came to the face, which was not shown on the charts of the time. The question was answered quickly enough: as the depth contour on the accompanying aerial photograph shows, the outer face was the edge of the trough. With the water crystal clear and the reef sloping steeply, at 50 meters the face looks much as it did at 10 meters—a death trap for divers, for it gives no sense of depth. Divers do, however, experience a distinct fear, for the face is patrolled by hundreds of sharks, mostly harmless reef sharks and many 2-meter-long “silver-tips”; nevertheless, every ten minutes or so one spots a larger one, a bull shark or a tiger shark. Tiger sharks are not so much dangerous—they tend to ignore divers—as simply big. Certainly they remind divers to stick close to the reef—as well they may, given that the life there is vivid beyond description.

The reef face is a wall of coral: thick, solid colonies in the shallows, where the turbulence is strongest (see Plate 22), giving way to branching growth forms at greater depths. The profusion of life everywhere gives divers pause—to stop, to rest, to think, and to marvel about the life around them, to wonder about eons past when this face was dry land, or to speculate about what it was like when humans may have walked where the deepest corals now grow. These can only be fleeting thoughts, however, for divers must never give in to the reef’s siren call: they can afford only a short time to muse before they must head back up the face to a decompression stop or a waiting boat.

Emerging Science: Its Guises and Gaps

Looking back, I think that this book had its beginnings while I was on a dive on Tijou Reef during the summer of 1973. I remember thinking then that the reefs we were visiting must be very old, for surely they had piggybacked on Australia’s coast as she drifted north from Antarctica. But then I wondered if it would not have been too cold for corals at such times. If so, where did the corals come from, and why did they bother to build such enormous ramparts that apparently serve no purpose? Did fish and all other reef life come and go with the corals? How is it that most reefs are planed off at precisely the same level, even though sea level has apparently always been rising and falling? What did this immense area look like when there was no ocean covering it? I found it hard to accept the idea that people had probably once lived in caves that were now submerged far below me.

Figure 1.1 Tijou Reef, a ribbon reef mostly 1 kilometer wide. The white line along the eastern side is the 1,000-meter depth contour; the numbers to the left are depths in meters. The arrow indicates the position of Walker’s Caves, described in Chapter 12 and illustrated in Plate 42. (Aerial collage by Geoscience Australia, Commonwealth of Australia.)

Coral reefs tend to engender these kinds of thoughts, and theories about them abound, some branching in the most unlikely directions. Even back in the 1970s I had a feeling that, despite its grandiose proportions and seeming indestructibility, the GBR was really a puppet on a string, at the mercy of events in other parts of the world. I soon learned that extraterrestrial forces, such as eccentricities of the Earth’s orbit around the sun, might have had a hand in its history, and that great events in the geological past had repeatedly brought reef-building corals close to extinction. But how?

The beginnings of this book had been written in notebooks by the late 1970s. Had I turned those scribbles into something readable back then, some parts of that book would indeed have been similar to what appears in these pages. The GBR was the same place of tantalizing beauty and mystery then as it is today. We would have marveled then, as we do now, at the myriad of ecological interactions, interdependencies, and fascinating life histories of so many of its inhabitants. We would have examined the significance of each biological, geological, or oceanographic discovery—the sediments, the water chemistry, and the revelations of drilling projects. Much of that book would also have focused on the remote past—but it would have been followed by a rather different version of the birth and history of what we see today.

Certainly the relationship between humans and the reef would have been described very differently. In the 1970s, conservation issues might have accounted for only a page or two of my book, for the GBR seemed more than big enough to look after itself, and what few issues there were seemed to fall easily within the scope of the newly constituted marine park authority. The only real cloud on the horizon was that ever-present menace, the crown-of-thorns starfish. Of all the negative impacts we are aware of today, it—and perhaps it alone—has remained unchanged over the decades.

So, despite the similarities, a 1970s version of this book would have had a very different emphasis and range of subject matter, for much of today’s science and many of our current concerns were wholly unknown—even unimaginable—back then. In the 1970s I might have ended the book with a heartwarming bromide: “And now we can rest assured that future generations will treasure this great wilderness area for all time.” Today, as we are coming to grips with the influence that humans are having on the world’s environments, it will come as no surprise that I am unable to write anything remotely like that ending.

Before 1980, El Niño events and enhanced (meaning human-induced) greenhouse warming seemingly had little to do with coral reefs. Then, in 1982, I saw for myself the aftermath of a mass bleaching event. Since then it has become increasingly clear that the implications of climate change cannot be fully understood without integrating the findings of many scientific and political disciplines, spanning such wide-ranging and sometimes unlikely subjects as sunspots, carbonate buffers, bolides, oxygen radicals, the Ocean Conveyor, Cretaceous CO2, Paleocene methane, the human population explosion, and international politics.

Whirlwind Tours, Links, and Syntheses

This book, therefore, is not simply an exposé of reef science as applied to the GBR. What I offer here is a much broader view that takes in aspects of general biology, oceanography, evolutionary theory, paleontology, reef geology, and ocean chemistry and combines them with what we know of ancient climates and current concepts of climate change. The fabric of our knowledge can be likened to a fishing net that, though often mended, is nonetheless still full of holes. The netting itself is woven from the many strands of science—at least the strands that seem to me to matter—and the mends are the spots where I have taken patches from one set of scientific findings and used them to fix holes in another. To fashion these patches I have made do with the best information at hand, occasionally improvising where the science is altogether missing. In such instances, I have endeavored to make a clear distinction between what is science and what is improvisation. My aim throughout is to make the big picture as accurate and as clear as possible, looking toward the future with the advantage of hindsight.

Inevitably, this book takes whirlwind tours through many different sciences. I do not visit these in isolation, for my purpose can only be served by linking them together to form a cohesive whole. This has been no small task, for every discipline comes with a massive literature and a unique jargon. Not surprisingly, several readers of the manuscript asked me why I wrote this book by myself. Why didn’t I leave parts to others? Jared Diamond, facing the same problem in Guns, Germs and Steel, offers an explanation: “These requirements [the many fields of science considered] seem at first to demand a multi-author work. Yet that approach would be doomed at the outset, because the essence of the problem is to develop a unified synthesis. That consideration dictates single authorship, despite all the difficulties that it poses. Inevitably, that single author will have to sweat copiously in order to assimilate material from many disciplines, and will require guidance from many colleagues.”1

And so we come to the inadequacies of language—of words that have very different meanings across discipline boundaries. In everyday language we use the strongest of terms—“disasters,”“catastrophes”—to describe the impact on humans of natural events such as earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, droughts, and forest fires. Yet in a geological context these events are insignificant trivia. In fact there have been no natural events in all of written human history that rate any mention on the scale of our planet’s history. Not so for the natural events that coral reefs have survived, and thus the problem for me is inescapable unless I resort to technical terms—jargon, words that have a clear meaning for those who have expertise in a particular subject yet are meaningless to everybody else. A couple of examples relevant to humans make the point. Mass extinctions are universally described as “events,” yet all have taken longer to occur than our species, Homo sapiens, has existed. Many sea-level fluctuations of the distant past described as “rapid” have taken longer to occur than the total span of human civilization.

Many terms in this book can be ambiguous, even such basic words as “limestone,” “reef,” “coral reef,” and “coral” as well as many marine terms, such as “plankton” and “substrate.” These are explained either in the text when they are first used or else in the glossary. Unavoidably, I must use a few technical terms like “thermohaline circulation,” “El Niño event,”and “orbital forcing,” as there are no alternatives. I also use the names of geological intervals without reservation, although I am aware that these have little meaning for nonspecialists. To help put such terms into context, explanatory time-line diagrams have been added to relevant chapters, and time intervals expressed in millions of years ago (mya) are sprinkled liberally throughout the text—a convention helpful to many if irritating to some. Yet problems that surround the concept of time are in a class of their own.

Time in Context

We use the same array of adjectives—“abrupt,” “rapid,” “gradual,” “constant,” and so on—to describe all manner of time intervals, no matter what the context—geological, evolutionary, biological, or human. Nevertheless, as in the previous examples, an event seen as major in one time frame may be irrelevant in another. These distinctions really do matter. For example, throughout this book I provide diagrams to depict changes in various physical environmental factors such as atmospheric CO2 levels or global temperatures. Each serves a purpose in its temporal context—yet other diagrams of the same factors set in different time intervals would appear to tell a very different story. (I have, for instance, used four such diagrams to depict atmospheric CO2 levels.) Context is everything, and the miscommunications created when context is not appreciated continue to plague us.

Time on a geological scale, like distance in space, is easily read or written about. Geological intervals have names (like “Triassic”) for easy reference, and if one prefers to express those names in years (like “251,000,000 to 206,000,000 years ago”) it is easy to look them up or memorize them: the numbers are mostly zeroes anyway. It is thus a simple matter to be precise about time. It is, howev...