- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Human Factors in Nuclear Safety

About this book

There is a growing recognition amongst those involved with the creation and distribution of nuclear power of the value and positive impact of ergonomics, recognition heightened by the realization that safety incidents are rarely the result of purely technical failure. This work provides insights into plant design, performance shaping factors,

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Human Factors in Nuclear Safety by Neville A. Stanton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The discipline of human factors?

NEVILLE STANTON

Department of Psychology, University of Southampton

1.1 What is Human Factors?

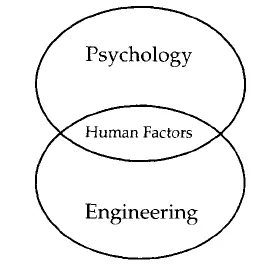

Most countries in the world have a national Human Factors/Ergonomics Society, for example, The Ergonomics Society in Great Britain (phone/fax from the UK 01509 234904) and the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society in the USA (phone from the UK 00 1 213 394 1811). According to Oborne (1982) initial interest in human-factors-related interests was conceived around the early 1900s, particularly problems related to increases in the production of munitions at factories during the First World War. The discipline was officially born at a multidisciplinary meeting held at the Admiralty in the UK on human work problems. We have an accurate recording of the date of this meeting, as can be expected of the armed services, and hence the birth of the discipline can be dated as 12 July 1949. The discipline was named at a subsequent meeting on 16 February 1950. To quote Oborne, ‘The word ergonomics [cf. ‘human factors’] was coined from the Greek: ergon—work, and nomos—natural laws.’ (Oborne, 1982, p. 3.) The disciples of the discipline were initially concerned with human problems at work (on both sides of the Atlantic), in particular with the interaction between humans and machines and the resultant effect upon productivity. This focus has been broadened somewhat since then to include all aspects of the working environment. Figure 1.1 distinguishes human factors from psychology and engineering.

Human factors (HF) is concerned about the relationship between human and technology with regard to some goal-directed activity. Whereas engineering is concerned with improving technology in terms of mechanical and electronic design and psychology is concerned with understanding human functioning, HF is concerned with adapting technology and the environment to the capacities and limitations of humans with the overall objective of improving performance of the whole human-technology system. There are plenty of examples to show the consequences of the mismatch between human-technology systems: Zeebrugge, Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, Bhopal and Challenger. These disasters have an obvious and dramatic effect. Other forms of mismatch may have more insidious effects, e.g. reducing productivity and affecting employees’ health. A systems viewpoint is taken in HF, to consider how human and technological systems can work together in a harmonious manner.

Figure 1.1 Distinction of human factors.

HF has emerged as a new discipline over the past 40 years in response to technological development. The role of HF is essential in the application of technological systems, as it focuses on the role of human involvement. The approach of HF is systematic, applying relevant and available information concerning human capabilities, characteristics, limitations, behaviour and motivation. In this sense, the problem space of HF can be defined as any system that requires human involvement. Thus the scope of HF covers the following:

- analysis, measurement, research and prediction of any human performance related to the operation, maintenance, or use of equipment or subsystem;

- research on the behavioural variables involved in the design of equipment, jobs and systems;

- the application of behavioural knowledge and methods to the development of equipment, jobs and systems;

- the analysis of jobs and systems to assist in the optimal allocation of personnel roles in system operation;

- research on the experiences and attitudes that equipment users and system personnel have with regard to equipment and systems;

- the study of the effects of equipment and system characteristics on personnel performance.

(from Miester, 1989).

Thus, the scope of HF is both broad and multi-disciplinary in nature. HF is a bridging discipline between psychology and engineering. As such it is able to

offer input into most aspects of human-technology systems. Two general definitions of HF illustrate this point:

The term ‘human factors’ is used here to cover a range of issues. They include the perceptual, mental and physical capabilities of people and the interactions of individuals with their job and working environments, the influence of equipment and system design on human performance and, above all, the organisational characteristics which influence safety related behaviour at work.

Source: HSE (1989).

[Human factors is…] the study of how humans accomplish work-related tasks in the context of human-machine system operation and how behavioural and non-behavioural variables affect that accomplishment. Human factors is also the application of behavioural principles to the design, development, testing and operation of equipment and systems.

Source: Miester (1989).

These definitions highlight the need to consider the interactions between individuals, jobs, the working environment, the equipment, system design and the organisation. Given the continuity, and nature, of the interaction between different elements of complex systems, it is necessary to develop an integrated approach if the analysis is to be effective. The main objectives of HF are to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the work system (i.e. the ease with which the symbiosis between humans and technology occurs) as well as reducing errors, fatigue and stress. Thus, it also aims to improve safety, comfort, job satisfaction and quality of working life (Sanders and McCormick, 1993).

Stanton and Baber (1991) offer four views of HF:

- a discipline which seeks to apply natural laws of human behaviour to the design of workplaces and equipment;

- a multidisciplinary approach to issues surrounding people at work;

- a discipline that seeks to maximise safety, efficiency and comfort by shaping the workplace or machine to physical and psychological capabilities of the operator;

- a concept, a way of looking at the world and thinking about how people work and how they cope.

Each of these views offers a subtly different perspective. The first suggests that ‘natural laws’ of human behaviour exist (e.g. Hick’s law and Fitt’s law), which can be applied to the design and evaluation of technological environments. Whilst such a view may produce important findings (which tend to be highly specific) it is dubious that such findings constitute immutable laws. This leads to the second viewpoint which draws on a potpourri of different subject matter.

Alternatively the third viewpoint emphasises the need to design the job to fit the person. Problems with this approach arise from attempting to define the ‘average person’. Finally the fourth viewpoint develops a notion of HF as an attitude: first it is necessary to recognise the need, then it is necessary to employ a body of knowledge and a set of skills to satisfy this need. Stanton and Baber favour the final view as it is distinctly different from the first three, it proposes HF as a philosophy rather than an ‘add-on’ approach; HF provides an overview of the human-technology system, rather than a discrete aspect of the system.

1.2 Human Factors Methodology

HF has developed approaches with which to combine different methods to study aspects of the workplace. In satisfying the need for improved HF we should consider what we mean by the overused clichés, ‘user friendly’ and ‘user-centred design’. These phrases do not just mean asking the users what they want of a system, because often users may not be fully aware of the range of possibilities. Rather, this terminology highlights the need to design for the user, taking account of their capabilities and capacities. The HF engineer offers a structured methodological approach to the human aspects of system design. Traditionally HF assessments have been performed at the end of the design cycle, when a finished system can be evaluated. However, it has been noted that the resulting changes proposed may be substantial and costly. This has led to a call for HF to be more prominent in the earlier aspects of design.

HF engineers are particularly keen to be involved in user evaluations earlier on in the design process, where it is more cost effective to make changes. Prototyping is one means of achieving this. Developing prototypes enables the users to have a contribution towards the design process. In this way identified problems may be reduced well before the final implementation of the system. The contributions of the user do not only take the form of expressed likes and dislikes. Performance testing is also very useful. This could include both physiological measures (Gale and Christie, 1987) and psychological measures (e.g. speed of performance and the type of errors made). User participation may also provide the designers with a greater insight into the needs of the users. This can be particularly important when the users may not be able clearly to express what features they desire of the system, as they are likely to be unaware of all the possibilities that could be made available. It is important to remember that human factor specialists typically work alongside engineers and designers. The human factors specialists bring an understanding of human capabilities to the team, whilst the engineers bring a clear understanding of the machines’ capabilities. These two approaches may mean that the final system is more ‘usable’ than would have been achieved if either the team components had worked alone.

1.3 Human Factors Applications

HF applications can be broadly divided into the following areas:

- specifying systems;

- designing systems;

- evaluating systems (does it meet own specifications?);

- assessing systems (does it meet HF specifications?).

This gives a field of activity comprising specification, design, evaluation and assessment. HF begins with an overall approach which considers the user(s), the task(s) and the technology involved, and aims to derive a solution which welds these aspects together. This is in contrast to the prevailing systems design view which considers each aspect as an isolated component. HF can provide a structured, objective investigation of the human aspects of system design, assessment and evaluation. The methods will be selected on the basis of the resources available. The resources will include time limits of project, funds, and the skills of the practitioners. Overall, HF can be viewed as an attitude to the specification, design, evaluation and assessment of work systems. It requires practitioners to recognise the need for HF, draw on the available body of knowledge and employ an appropriate range of methods and techniques to satisfy this need. It offers support to traditional design activity by permitting the structured and objective study of human behaviour in the workplace.

From the discussion it is apparent that HF has a useful contribution to offer. There is an awakening to this as the impending legislation demonstrates. The contribution comes in the form of a body of knowledge, methods and above all an attitude inherent in the HF approach. It is this attitude that provides HF with a novel perspective and defines its scope. HF has much to offer designers and engineers of technological systems, and this could be no more true than in the domain of the nuclear industry.

1.4 Human Factors in Nuclear Safety

There is an increasing awareness amongst the nuclear power community of the importance of considering human factors in the design, operation, maintenance and decommissioning of nuclear power plants. Woods et al. (1987) suggest nuclear power plants present a considerable challenge to the HF community, and their review concentrates upon control room design. Reason (1990a) reports that 92% of all significant events in nuclear utilities between 1983 and 1984 (based upon the analysis of 180 reports of INPO members) were man-made and, of these, only 8% were initiated by the control room operator. Thus, the scope of HF needs to consider all aspects of the human-technology system. The consideration of the human element of the system has been taken very seriously since the publication of the President’s Commission’s report on Three Mile Island (Kemeny, 1979) which brought serious HF problems to the forefront. In summary of the main findings the commission reports a series of ‘human, institutional and mechanical failures’. It was concluded that the basic problems were people-related, i.e. the human aspects of the system that manufactures, operates and regulates nuclear power. Some reports have suggested ‘operator error’ as the prime cause of the event, but this shows a limited understanding of HF. The failings at TMI included:

- deficient training that left operators unprepared to handle serious accidents;

- inadequate and confusing operating procedures that could have led the operators to incorrect actions;

- design deficiencies in the control room, for example in the way in which information was presented and controls were laid out;

- serious managerial problems within the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

None of the deficiencies accounts for the root cause of the incident as ‘operator error’, which is an all too familiar explanation in incidents involving humantechnology systems. Reason (1987) in an analysis of the Chernobyl incident suggested two main factors of concern. The first factor relates to the cognitive difficulties of managing complex systems: people have difficulties in understanding the full effects of their actions on the whole of the system. The second factor relates to a syndrome called ‘groupthink’: small, cohesive and elite groups can become unswerving in their pursuit of an unsuitable course of action. Reason cautions against the rhetoric of ‘it couldn’t happen here’ because, as he argues, one of the basic system elements (i.e. people) is common to all nuclear power systems. Most of the HF issues surrounding the problems identified in the analyses of TMI and Chernobyl can be found within this book. A committee was set up in the UK to advise the nuclear industry in the UK about how HF should be managed. The reports of this committee are the subject of the next section.

1.5 ACSNI Reports on Human Factors

The Advisory Committee on the Safety of Nuclear Installations (ACSNI) set up the Human Factors Study Group on 7 December 1987 to review curre...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter One The discipline of human factors?

- Part One Organisational Issues for Design

- Part Two Interface Design Issues

- Part Three Personnel Issue

- Part Four Organisational Issues for Safety