- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mechanisms and Concepts in Toxicology

About this book

Illustrating concepts and types of toxicity from a mechanistic point of view, this book focuses on research procedures in toxicology. The book uses examples of chemical intoxicants to illustrate mechanisms in each stage of toxicity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mechanisms and Concepts in Toxicology by W. Norman Aldridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Toxicology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Toxicology1

Scope of Toxicology

1.1

Toxicology and Mechanisms of Toxicity

Toxic substances have always been used by many species of animal including humans for defensive and offensive purposes. Textbooks of pharmacology are full of examples of such agents used by man, e.g. arrowhead poisons such as digitalis from Strophanthus and curare from Strychnos and Chondrodendron. Although there are many examples of man using natural toxins for his own purposes there are probably many more of one animal species using toxins to control another, to deter an attack by another, to immobilise a food source either for immediate or later consumption. Pharmacology has a rather positive image being concerned with the treatment of disease by natural products, structural modifications of natural products and by synthetic drugs designed for treatment of a particular disease. In contrast, toxicology is sometimes regarded in a negative way. This is a misconception, for in its wider context natural toxins have a respectable position in evolutionary development which has allowed the equilibrium between species to be attained and maintained. Man-made chemicals also have provided and will continue to provide protection by the control of disease vectors (in many species) and also enhanced comfort, convenience and security in modern society. Toxicology and pharmacology are complementary and the thought processes involved in mechanisms of toxicity are similar to those in pharmacology.

Novel therapeutic agents follow from new basic knowledge of disease processes and are now positively designed to interfere with a particular receptor. Even though it may be possible to design a chemical with a high affinity for a particular receptor it will not always result in an acceptable therapeutic agent. During the development of new chemical structures (drugs), undesirable and novel side-effects may appear in tests on experimental animals. Sometimes, even when a potential drug passes all safety checks, side-effects may appear during clinical trials or even after the drug’s release for general use. Such side-effects highlight areas of biological activity about which little is known and new biological research is required.

The meaning of mechanistic and mechanisms when applied to toxicology is not always clear. It is often limited as if it were only research which established the primary interaction of a chemical with a macromolecule as the initiating event for the disease. This is an unhelpful and unnecessarily narrow view. Studies in the area of mechanisms are those whose purpose and intention is to provide a holistic view of the process of toxicity; there are many levels of biological complexity which, when combined, allow a reasonable hypothesis of each mechanism of toxicity to be stated.

In a historical context, mechanistic toxicology could not begin before a certain knowledge in basic biology. Research in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, largely on plants by Hooke and vøn Leeuwenhoek, led to the view that tissues consisted of many small entities, i.e. cells. The importance of the nucleus as a feature of all cells was promoted by Schwann, Purkinje, Brown and Schleiden followed by Virchow’s clear statements:

- All living organisms are composed of nucleated cells.

- Cells are the functional units of life.

- Cells arise only from pre-existing cells by dividing.

The foundation on which scientific toxicology developed probably derives from the work of Orfila who lived in times of great advancement in chemistry, physiology and pathology. In the early nineteenth century, Orfila was the first to treat toxicology as a separate scientific subject and introduced chemical analysis as an essential component. His first textbook on general toxicology laid the foundation of experimental and particularly forensic toxicology. During the same period Magendie was making many discoveries which became the basis for the experimental analysis of the site of action of poisons (for an extensive discussion of the contributions of Orfila and Magendie see Holmstedt & Liljestrand, 1963). Later in the nineteenth century it became clear that toxic substances could be useful as tools for the dissection of living tissues and thus to learn about the way they are organised in a functional sense (see Preface; Bernard, 1875).

Following such work and the ability to identify by histopathological techniques the tissue and cells attacked by a toxic substance, advances in many relevant sciences took place, e.g. methods for the separation of the active principles of plants, morphological detail of the structural arrangement of cells, the relationship between organ and cell function and the biochemical reactions occurring in them. The development of the electron microscope has led to understanding of intracellular organisation, e.g. subcellular organelles and the existence of other compartments. Methods for the separation by fractionation of tissues and of cells in a functioning state are now being devised so that reactions can be studied in vitro under controlled conditions separate from the controlling influences the whole organism. Analytical methods of great finesse are now available for the separation and identification of small and large molecules.

These advances in the biological sciences signalled that there was a reasonable expectation that mechanisms of toxicity should be able to be identified at the cell level and often down to changes in reactions occurring within cells and sometimes to a specific interaction with a macromolecule. The latter is an early event in contrast to changes in morphology which indeed may be a rather late consequence of the primary chemical event. The concept of a ‘biochemical lesion’ was first proposed by Rudolf Peters as a result of research on the effects of vitamin B (thiamine) deficiency (Gavrilescu & Peters, 1931) and was later used following research on the toxicity of vesicants such as the arsenical, lewisite (Peters et al., 1945) and on the intoxicant fluoroacetate (Peters, 1963); in the latter the concept of ‘lethal synthesis’ was also introduced. Lethal synthesis is when the toxicity of a chemical is changed and increased by biological conversion of one chemical to another.

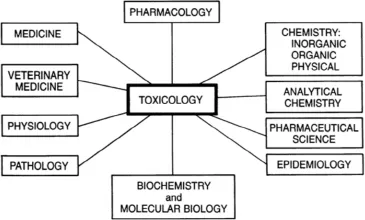

Thus understanding in toxicology depends on information derived from many other disciplines, i.e. toxicology is an interdisciplinary subject (Figure 1.1). This is not exceptional for biological disciplines e.g. pharmacology, physiology, microbiology and so on. As in other areas of biology, in addition to the importance of the acquisition of new information, mechanisms of toxicity provide the intellectual climate for the solution of practical problems in toxicology and the subject moves from a descriptive to a predictive science.

Figure 1.1 Areas of scientific study relevant to toxicology. These relationships imply that crucial steps catalytic for progress in mechanisms of toxicity may arise from research, not only in departments or institutes of toxicology but also in many other areas

1.2

Definition of Toxicology and Toxicity

- Toxicity by chemicals is changes from the normal in either the structure or function of living organisms or both.

- Chemicals causing toxicity are intoxicants or poisons.

- Toxicology is the science of poisons.

These definitions are wide and open-ended with respect to organisms, responses and toxic chemicals.

1.2.1

Organisms

The aim of most studies is to provide safety for human beings. In the past half century there has been a radical change in public attitudes about exposure to chemicals. Prior to 1940 few chemicals were synthesised in large amounts and exposure often occurred during the mining of metals and their subsequent purification and fabrication. If illness resulted, then following medical advice conditions were improved. For a variety of reasons attitudes have changed; these include the advance of chemistry, the increased longevity due to treatment of infectious diseases and better nutrition, and an awareness through education of the possibilities of toxicity. It is now generally accepted that before (not after) a chemical (pesticide, drug, etc), is used, industry and governmental authorities take responsibility for ensuring that sufficient information about potential hazard is available to protect the public. This has resulted in a huge increase in the use of experimental animals for toxicity testing and for research.

Veterinary practice has always been faced with toxicological problems. Some are accidental as in the feeding to livestock of feed supplement containing polybrominated biphenyls instead of magnesium oxide (Dunckel, 1975). Other examples are the fatal exposure of animals in the Seveso episode (Holmstedt, 1980), drinking water contaminated by toxic cyanobacteria (Carmichael et al., 1985) and consumption of feed on which organisms have grown and produced toxic metabolites as in the initial poisoning of turkeys with aflatoxin (Stoloff, 1977). Toxic plants in fields and pastures have always been a cause of poisoning in animals, e.g. consumption of ragwort containing the toxic Senecio alkaloids (WHO, 1988; Mattocks, 1986).

While the egocentric attitudes of humans have provided the main driving force for the evaluation of the toxicity of new chemicals in recent years there has been a growing view that the ecological balance in nature should be preserved. This view may be challenged and debated in extenso; it has resulted in greater attention being given to effects of chemicals on species other than the usual experimental and farm animals. For example, fish toxicity is now considered necessary before the introduction of most pesticides and the toxicity of effluent resulting from their manufacture is more carefully evaluated. The range of organisms which can be studied from a toxicological point of view is potentially very large. In many cases where exposure to chemicals is postulated to be the cause of the change in the population of particular organisms, proof that this is so often necessitates much more information and research (see Chapter 13).

The increase in the use of animals for experimental purposes has resulted in demands from some members of the public for the introduction of in vitro techniques to replace them or at least to diminish their numbers; they might utilise a pure enzyme, isolated animal tissues and in some cases model bacterial systems (see Chapter 10).

As a consequence of all the above demands, the range of species of organism and biological systems to be considered in a toxicological context is now very large and is increasing. This expanding range is mainly being driven by questions of a practical nature but, in another context, researchers in biological science have always been prepared to widen their studies to other species in order to solve particular academic problems (e.g. when an animal model is not available within the usual range of experimental animals; see Chapter 10).

1.2.2

Responses

Current perception is that the range of responses is almost infinite; any attempt to produce a useful list for the huge range of potentially affected organisms would fail. Sometimes the site of toxicity is decided by the route of exposure, e.g. through the skin, by inhalation or by absorption from the gastro-intestinal tract, when the toxicity evinced may be to the skin, to the lung, etc. However, all responses are not of equal practical importance. In most cases tissue damage (e.g. loss of cells) can be repaired by mitosis from remaining cells. Thus ingestion of the commonly consumed chemical ethyl alcohol no doubt from time to time causes the death of some hepatocytes but provokes few long-term consequences due to efficient repair processes. However, neuronal loss is permanent and although this may not be clinically significant owing to a large reserve capacity, a permanent change has taken place. Damage to long axons in the central (spinal cord) and peripheral (sciatic nerves) has different long-term consequences; peripheral nerves can be repaired and reach the end organ while axons of central nerves do not reconnect. Secondary consequences in the whole organism, such as scar tissue formation or long lasting inflammatory processes, clinical signs or symptoms which after a short exposure take a long time to appear or which require a long exposure, continue to present challenges to our current understanding in biology and toxicology (see Chapter 8).

Some chemicals cause toxicity following a reversible interaction with a tissue component, whereas others interact to yield a covalently bonded and modified tissue component. Biological consequences of such interactions can be very different but much remains to be explored, particularly in relation to chronic and long lasting toxicity (see Chapter 7).

Clinical responses are obviously emphasised but one of the most important tasks in toxicology is to identify early interactions which result in changes...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Scope of Toxicology

- 2: Stages in the Induction of Toxicity

- 3: Kinetics and End-points

- 4: Acute and Chronic Intoxication

- 5: Delivery of Intoxicant Decrease in delivery to the target

- 6: Delivery of Intoxicant

- 7: Initiating Reactions with Targets

- 8: Biological Consequences of Initiating Reactions with Targets

- 9: Exposure, Dose and Chemical Structure, Response and Activity, and Thresholds

- 10: Selective Toxicity, Animal Experimentation and In Vitro Methods

- 11: Biomonitoring

- 12: Epidemiology

- 13: Environmental and Ecotoxicology

- 14: Reflections, Research and Risk

- References