- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is a collection of essays on the history and philosophy of evolutionary biology by the well-known Canadian scholar, Michael Ruse. Much has been written newly for the collection, as the author explores themes of evolutionary naturalism, putting the theory of knowledge and of moral behaviour on a philosophical basis informed by contemporary evolutionary biology. Divided into three parts, the first set of essays considers issues in the history of science - Darwin, population biology, and the new paleontological theory of `punctuated equilibria' - attempting to find a path between the crude objectivity espoused by many working scientists, and the rank relativism of post-modernist critiques of science. The second set of essays turns directly to the theory of knowledge (epistemology), arguing that the fact that we are evolved beings rather than objects of special creation, must and does inform our thinking about the external world. The third set of essays, the most controversial, turns to questions of morality, arguing that ethical systems are ultimately no more than collective illusions put in place by our biology, because humans are essentially social animals. Written in a clear and non-technical fashion, this collection carries forward debate on a number of controversial issues, showing that the time has now come to take philosophy from the hands of academic theorists and to embrace fully the findings and consequences of modern science.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & TheoryPart I

CASE STUDIES

INTRODUCTION

The three papers in this section deal with three items from the history of evolutionary biology – items separated by roughly fifty-year intervals, from Darwin to the time when genetics was brought into evolutionary thought in the earlier parts of this century, and from this second time to the present day, when evolutionary studies thrive as perhaps never before. I begin with the genesis of the mechanism of natural selection, taking as my theme the different routes pursued by the two co-discoverers, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace; I move next to the thought of the American population geneticist Sewall Wright, and the significance of his picture of an adaptive landscape; and I end with the recent palaeontological theory of ‘punctuated equilibria’, trying to assess the extent to which, and reasons why, it has proven controversial.

But, as stated in my Introduction, I am not interested in history just for its own sake. I want to explore and test philosophical ideas. Most immediately, I am concerned with the issues of discovery, display and dispute. Uniting this section, however, is my attempt to find a theory of scientific knowledge which captures what I believe all three of my case studies show, namely that science has both an objective side, something which tells us about a real world ‘out there’, and a subjective side, a reflection of the culture in which the science is formed.

The first essay, on Darwin and Wallace, was written some ten years before the others, a fact which it does show, somewhat. I do not offer it as a testament to my earlier immaturity or to the development since, but to show how someone who took very seriously both the spinning and the fabric of science, could be led to a position which wanted to bridge or to break the objective/subjective divide. I do note, however, that although I did not then have a formal or articulated general system that I was endorsing, I was sensitive to the nature and use of metaphor in science. I can certainly attest that this was one of the main things which made me sympathetic, in the years shortly after, to the ‘internal realist’ position of the American philosopher Hilary Putnam, which is the epistemology against which I try to place my discussion in the second essay, and which underlies my thinking at the end of the third.

I appreciate that, from a conceptual viewpoint, ‘placing’ is about the best I can hope for at this point. I am certainly not ‘proving’ my favoured philosophy. But it could be that Thomas Kuhn in his influential Structure of Scientific Revolutions is right, and that for most scientists most of the time, the reality is ‘normal science’, which means working away at problems set within an accepted overall background or ‘paradigm’. As a philosophical naturalist perhaps I should be happy that I now have my paradigm, internal realism, and that it is thus open to me to do normal science precisely because I have an overall position, which I am using more than I am justifying.

1

OUGHT PHILOSOPHERS CONSIDER SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY?

A Darwinian case study

My concern in this paper will be with Darwin’s discovery of his theory of evolution, particularly the part centred on its mechanisms. What I want to know is whether knowledge of Darwin’s route to discovery tells us something about the finished theory, say as it is found in the first edition of The Origin of Species (1859). Do we, as philosophers, need to know how Darwin got his theory in order to understand his theory? I take it that there is a school of philosophical thought, ‘logical empiricism’, that would argue that essentially a scientist’s route to discovery is irrelevant to his or her finished product. A scientific theory or hypothesis is in some sense intended to be a reflection of reality. Hence, that a scientist may have got his ideas after years of painstaking fitting of the data to possible ideas, like Kepler, or in a flash through mystical contemplation of his navel, is of absolutely no concern.1 Even if Archimedes had never taken a bath in his life, his principle would still have been the same.

I assume that it is this kind of philosophy of scientific discovery (i.e. that there can be no significant philosophy of scientific discovery) that underlies Carl Hempel’s quick dismissal of discovery in his (excellent) little textbook, Philosophy of Natural Science (1966). A scientist may hit on an idea by the craziest of means, like Kekulé finding the benzine ring through dreaming of a snake swallowing its tail, but the ‘real’ science has no place for this. Were a herpetologist to complain that benzine cannot be circular because snakes do not swallow their tails, his worries would be dismissed as inappropriate. A similar philosophy seems to be held by Karl Popper, who has the singular distinction of having written a book called The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959), which is not about scientific discovery at all. In a more recent paper, Popper states: ‘[T]o me the idea of turning for enlightenment concerning the aims of science, and its possible progress, to sociology or to psychology (or… to the history of science) is surprising and disappointing’ (1970: 57). And someone like Mario Bunge (1968) seems almost to want us to forget discovery as soon as possible, so that we might not illegitimately read into our theory things which helped us to get to the theory – otherwise we shall start worrying about whether the benzine ring is cold blooded and whether bath salts are necessary for a true application of Archimedes’ Principle!2

I shall argue that this belittling view of scientific discovery is wrong: philosophically castrating in fact. Let us turn at once to history.

DARWIN’S ROUTE TO DISCOVERY

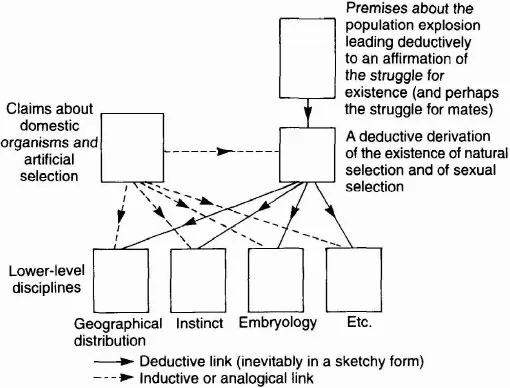

Charles Darwin published his Origin of Species late in 1859. For reasons which are not entirely clear, Darwin had been sitting on his idea for twenty years – it had in fact been fifteen years since he had completed a 230-page draft of his theory3 – and even when he did publish it, it was only because he had been sent a paper by the young naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace (Darwin and Wallace 1858), which contained evolutionary speculations uncannily like his own. As is well known, Darwin argued that evolution is chiefly a function of ‘natural selection’, the differential survival and reproduction of the more adapted over the less adapted, and that this in turn is fuelled by the ‘struggle for existence’, where animals and plants compete with each other and the environment for limited resources. Then, having produced his mechanism, Darwin applied it to many different areas of biology – geographical distribution (biogeography), instinct, embryology, and others (see Figure 1.1).

The crucial move to natural selection as an evolutionary mechanism was made by Darwin in the autumn of 1838: late September to early October, to be more precise. However, controversy exists over precisely how Darwin moved to natural selection. In his Autobiography (1969), Darwin claimed that the work of animal and plant breeders using artificial selection gave him the notion of natural selection, and then reading Malthus’ Principle of Population (1826), with its description of the struggle for existence – a function of geometric population growth potential always outstripping food and space arithmetic growth potential – showed him how to apply selection as a mechanism for evolution. And this route to discovery is confirmed by several other recollections by Darwin of his momentous discovery.

Figure 1.1 The structure of Darwin’s theory in the Origin. From Ruse 1975b

But this account of discovery does not mesh very easily with entries Darwin made in notebooks around the time of the discovery. The importance of Malthus is reinforced, but the key role played by the artificial/natural selection analogy is put in doubt. From comments Darwin made right up to the time that he read Malthus, he seems to have had some doubts about the power of artificial selection and the consequent analogy to natural selection. ‘It certainly appears in domesticated animals that the amount of variation is soon reached – as in pigeons no new races’ (Darwin 1960: D175). And indeed, some scholars have concluded on the basis of this and like passages that Darwin did not really use the analogy from the domestic world in his discovery of natural selection (see Herbert 1971 and Limoges 1970). Others, however, are loath to make a liar out of Darwin. My own position, which I shall state but not really argue for here, is that although Darwin was not as certain of the value of the analogy before Malthus as he became afterwards (and thought that he had been before), the analogy did indeed play an important part in Darwin’s discovery. (I do argue my case in Ruse 1975a and 1979a.)

I argue this claim chiefly on the basis of what Darwin read in the months before he read Malthus. We know that in the summer of 1838 Darwin read influential pamphlets on animal breeding, in which the principles of selection were clearly stated, and the analogy was even drawn between the artificial and natural worlds! ‘A severe winter, or a scarcity of food, by destroying the weak and the unhealthy, has all the good effects of the most skilful selection’ (Sebright 1809: 16). We know also that Darwin reacted enthusiastically to this reading and that at that point he did some speculating about the effects of continued selection – how it would lead to new species. So for these and related reasons, I believe and shall assume that the analogy from the domestic world – specifically including the analogy from artificial selection – was important to Darwin in his discovery of natural selection.4

THE CASE AGAINST THE IMPORTANCE OF THE PATH OF DISCOVERY

But where does all this take us? Darwin got his mechanism of natural selection, first from the analogy of artificial selection, and then from reading Malthus’ quasi-mathematical speculations about humans in his Principles (1826) (speculations, somewhat ironically given the use Darwin was to make of them, directed towards showing the futility of attempting any real progress or change). Does any of this matter when it comes to considering Darwin’s theory, or should we concern ourselves solely with the justifications Darwin offered: whether he relied on real laws, the precise nature of the links between his premises and conclusions, and so forth?

Considering matters first at a general level, and recognizing that initial suggestions will probably require some refinement, it should in theory be possible to decide empirically some of the pertinent questions about scientific discovery – at least in a one-way negative manner somewhat akin to the Popperian falsification of scientific hypotheses. Suppose one has a scientist A, who gets to theory T by route of discovery R. If one now has another scientist B, who also gets to theory T, but not by route of discovery R, one can certainly conclude that R was not necessary for getting to T, and therefore can hardly be that essential for understanding T: it is not going to be embedded in T in any significant way. This line of argument is one-way however, because if A gets to T via R, and B, not on R, does not get to T, there is always the logical possibility of a third scientist C who gets to T but not on route R.

Now, as I have just said, this is an empirical line of argument. If one has a situation with the right kinds of scientist, one can stop one’s a priori theorizing and check. And the beautiful thing about the Darwinian case is that one does have just such a situation with the right kinds of scientist: Wallace came to natural selection as well as, but quite independently of, Darwin.

Most or perhaps all the variations from the typical form of a species must have some definite effect, however slight, on the habits or capacities of the individuals…. [Consequently, if] any species should produce a variety having slightly increased powers of preserving existence, that variety must inevitably in time acquire a superiority in numbers.

(Darwin and Wallace 1858: 273)

And if this keeps happening long enough, the process ‘must in the end, produce its full legitimate results’ (ibid.: 275). What is of crucial importance to us here is that although Wallace was as dependent on Malthus as Darwin for getting to the mechanism, he did not use the artificial selection analogy. Indeed, like everyone but Darwin, Wallace looked upon the domestic world as one of the rightful pillars of the case against evolutionism! Domestic change is limited; therefore, any analogy is that natural change is limited.

...Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I Case studies

- Part II Evolutionary epistemology

- Part III Evolutionary ethics

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Evolutionary Naturalism by Michael Ruse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.