- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Japanese Industrialization and the Asian Economy

About this book

Much has been made of the post-war Japanese economic miracle. However, the origins of this spectacular success and its effect on the region can actually be traced back to an earlier period of Asian history. In Japanese Industrialization and the Asian Economy the authors examine the factors which contributed to the period of major industrialization

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Japanese Industrialization and the Asian Economy by Heita Kawakatsu,John Latham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE EMERGENCE OF A MARKET FOR COTTON GOODS IN EAST ASIA IN THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD

INTRODUCTION

Cotton was grown in India for several thousands of years before Christ and for a long time India monopolized the product. By the time Europeans and Japanese launched out into the so-called ‘East Indies’, cotton textiles were being used by the people of East Africa, the Middle East and South and South-East Asia, not only as clothing materials but also as a means of exchange. In the course of history from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, as trade began between the East Indies and the two extremities of Eurasia, cotton products found their way from India to the East and the West via various routes.

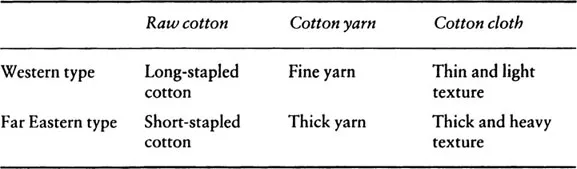

As indicated in my historical background note, two economic revolutions took place in Britain and in Japan: the industrial revolution in Britain, and the industrious revolution in Japan. These revolutions created an import-substitute industry for cotton goods: the British industry copied Indian goods, whereas the Japanese copied Chinese goods. As a result, what emerged were two markets for cotton products with distinct qualities, in the West and in the Far East respectively (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Two markets for cotton products

The following account describes when and how a particular type of cotton plant spread eastward, resulting in the creation of this market in East Asia.

CLASSIFICATION

The cotton plant belongs to the genus Gossypium, of the Hibiscus genus of the Mallow family. From the beginning of the study of Gossypium considerable difficulty was encountered in attempting to draw up the classification of its species. In early studies, Linnaeus, Parlatore (Le Specie dei cotoni, 1866), Bowman, Forbes Royle (Illustrations of Botany and Natural History of Himalayan Mountains, 1839) and Todaro (Relazione sulla culta dei cotoni, 1877–78) were notable botanists.1 These scholars differed greatly in the number of species they recognized. The number of species from a botanical point of view’, wrote Brooks in 1898, ‘is variously stated as from four to eighty-eight’.2 This disagreement took place because, during the period in which the cottons had been cultivated, selection had occurred, either consciously or unconsciously, resulting in the appearance in different places, but probably from the same stock, of well-marked forms which, in the absence of the history of their origins, must be regarded as different species.3 The most elaborate attempt at classification by the morphological approach was made by Watt in 1907.4 His main subdivisions of the species were largely based upon the presence or absence of fuzz on the seeds. This character, however, is inherited in simple Mendelian fashion, and it can be associated with any other group of characteristics. It is not strange, therefore, that of two forms otherwise similar, one may have very fuzzy and the other may have naked seeds. Classification on this basis is necessarily artificial. But the following two decades did not see any significant contribution to the taxonomy comparable to his.5

In 1928, the appearance of an article entitled ‘A contribution to the classification of the genus Gossypium’, written by a Russian botanist G.S. Zaitzev, brought a revolution in the taxonomy of Gossypium.6 Zaitzev, who made use of discoveries concerning the minute structure of the reproductive cells, adopted a genetic approach for the first time, a very different form of analysis from the morphological approach employed so far. What Zaitzev discovered was as follows:7

(a) The cotton forms of the Old World (Asia and Africa) have a haploid (in the sexual cells) number of chromosomes, 13; the corresponding diploid number in the somatic cells is 26. The cotton forms of the New World have a haploid chromosome number of 26; the corresponding diploid number is 52.

(b) Crosses between the cotton forms of the Old World and those of the New fail almost completely; when such crosses are effected, in a natural or an artificial way, they are, first, very rare; and second, the hybrids obtained from such crosses in the first generation are completely sterile in spite of their normal appearance. Because of such genetic differences, any interaction between the forms of the Old World and those of the New is entirely excluded (in spite of the statements of some botanists, especially Watt) and they are entirely isolated from one another.8

Furthermore, based on the experimental results that hybrid forms obtained from cotton plants belonging to different sub-groups were of only transitory importance and sooner or later died out or reverted to the ancestral forms, a fact showing the steadiness and independency of the sub-groups, he discovered that the cotton group of the New World and that of the Old World could be divided into two sub-groups respectively. Each of these two sub-groups had its own geographical distribution. Accordingly, he subdivided the Old World and the New World cottons into the African and the Indo-China (Asiatic) sub-groups of the former, and the Central American and the Southern American sub-groups of the latter.9 The cytological, morphological and physiological data which he collected, together with the genetic investigations of the genus Gossypium, also supported the fact that the genus Gossypium falls phylogenetically into the above four groups.10

Successive analyses by botanists have corroborated Zaitzev’s findings in respect of the genetic nature of the species, that is, only four species embrace the whole vast diversity of cultivated cottons. Zaitzev followed his predecessors’ (particularly Watt’s) nomenclature. His followers found the original species of each sub-group.

S.G. Harland, among others, who worked on the New World cotton with 26 chromosomes, established that:

(a) two species, namely G. barbadense and G. hirsutum are good taxonomic species;

(b) in these two species, long separation had produced profound genetic change;

(c) G. hirsutum and G. barbadense possess relatively few genetic attributes in common;

(d) geographical isolation over a long period of time had resulted in the production of new alleles at most loci and in a characteristic distribution of the differing alleles between the two species;

(e) although G. hirsutum and G. barbadense were so closely related that their first-generation hybrids were fully fertile, sterile and unviable types appeared in their second generation;

(f) the discontinuity between these entities in nature, even in the areas where their ranges overlapped, was taken to indicate that they were good taxonomic species.11

R.A. Silow made extensive investigations into the genetic aspects of taxonomic divergence in the diploid Asiatic cottons, and found that two cultivated Asiatic species, G. arboreum and G. herbaceum diverge in their genetic composition. He maintained that:

(a) taxonomically the relationship existing between G. arboreum and G. herbaceum was similar to that between the New World cultivated species, with full fertility in the first generation and partial sterility and disintegration in later generation;

(b) the separation of G. herbaceum from G. arboreum was not only by a genetic barrier, but also by ecological adaptabilities.12

Three independent lines of evidence confirm Silow’s findings:

(a) the species integrity was maintained when cultivated cottons were grown mixed in commercial crops; mixtures of G. arboreum and G. herbaceum were grown commercially in western India and in parts of Madras for many years without breakdown of the species distinction;13

(b) before the distinction between G. arboreum and G. herbaceum was worked out genetically, comprehensive and long-continued efforts were made in South India to breed commercially acceptable cottons from G. arboreum × G. herbaceum hybrids. These consistently failed to give material of agricultural value, and it was remarked that ‘the better the single plant selection in any generation, the worse the segregates that appeared in its progeny’;14

(c) in crosses made for the genetic analysis of species difference, there arose a wide range of unbalanced and unthrifty types in segregating generations.15

THE OLD WORLD COTTONS

Origin and spread

According to Watt, ‘no species of Gossypium is known, in its original habitat, to be annual.’16 Histo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Historical background

- 1. The Emergence of a Market for Cotton Goods in East Asia in the Early Modern Period

- 2. The Ceramic Trade in Asia, 1602–82

- 3. China and the Manila Galleons

- 4. The Tribute Trade System and Modern Asia

- 5. Bonded Warehouses and the Indent System, 1886–95: A study of the political power of British merchants in the Asian trade

- 6. Chinese Merchants and Chinese Inter-Port trade

- 7. The Dynamics of Intra-Asian Trade, 1868–1913: The Great Entrepôts of Singapore and Hong Kong

- 8. Sino-Japanese Trade and Japanese Industrialization

- 9. Japan’s East Asia Market, 1870–1940

- Index