eBook - ePub

World Yearbook of Education 1994

The Gender Gap in Higher Education

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Yearbook of Education 1994

The Gender Gap in Higher Education

About this book

This study surveys the position of women in academic institutions across the world, investigating the nature of the gender gap in various countries. The contributors analyze data, predict future trends and summarize those strategies most successful in reducing gender inequality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Yearbook of Education 1994 by Suzanne Lie, Lynda Malik, Suzanne Lie,Lynda Malik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1. The gender gap in higher education: a conceptual framework

Introduction

One of the most widely reported findings of the post-war era has been the ubiquitous presence of gender1 stratification. Although its occurrence is almost universally recognized, fundamental questions about its causes and development remain unanswered. The most important of these concern the reasons why every society appears to have an (implicit or explicit) hierarchy based on gender and the relative position of men and women within these hierarchies.

The first question is beyond the scope of this volume. Suffice it to say here that the combination of high maternal/infant mortality rates and short life expectancies which characterized our species for most of its life on this planet was undoubtedly related to the early development of gender role differences. In the post-industrial world these conditions no longer prevail and yet male and female gender roles are still everywhere differentiated.

Concerning the relative position on the hierarchy of men and women, a remarkable consistency appears to exist. In every society for which we have data, men occupy a disproportionate share of superordinate positions. This is true regardless of the criterion of classification (ie, income, prestige, power, etc.) and across national and ideological frontiers. Gender-based inequalities are marked in capitalist, socialist and formerly socialist societies, in rich and in poor ones, in religious societies and in secular ones and in cultures where values of equality are cherished as well as in those committed to inequality.

The gender gap in higher education: the problem defined

In this volume we propose to examine the relative position of men and women, ie, the gender gap, in higher education in 17 countries throughout the world: Australia, Botswana, Bulgaria, China, France, Greece, the Federal Republic of Germany, Iran, The Netherlands, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Uzbekistan.

Our focus is on women, particularly their changing position in higher education as students, faculty and administrators. In many societies the images, roles and behaviour of women are changing – in some countries this change is dramatic, in others it is not. The definition of higher education varies considerably from country to country. We have chosen to concentrate primarily on universities and research institutions because of their power as selecting, licensing and gate-keeping institutions. More importantly, they greatly influence and control definitions of knowledge and much, though not all, of the ideological machinery of the state and of society (Rendel, 1984). Academic women are of particular interest because they have the potential to play a critical role in shaping women and men of the future and, in addition to influencing the form and content of knowledge, they also serve as role models for female students.

We describe the gender gap in higher education as having both vertical and horizontal dimensions. The vertical aspects consist of rank, salary, and power differentials among faculty and administrators. The horizontal dimension relates to field of study among students and faculty. This gender gap is our dependent variable; we are interested in studying its size, characteristics and development in various historical and cultural contexts.

Our underlying aim is twofold. First, we hope to develop a picture of the dimensions of the gender gap in each country (in the individual chapters) along with a description of its history and relationship to significant aspects of the relevant cultural milieu. Second, in the conclusion we identify similarities and differences between countries and thereby attempt to arrive at low-level theoretical propositions which can be tested in the future.

More specifically, the following questions will be investigated:

• Is there a gender gap in higher education in the countries under investigation?

• Is it increasing or diminishing and under what conditions?

• How is the gender gap connected with economic, legislative, political and religious conditions of each country under study?

• Are current trends best explained by particular combinations of cultural, societal or individual level characteristics?

• Are there national or university policies which aim at gender equality in the countries under study? What have been their effects?

• Is there any relationship between the changing size of the gender gap and the development of the women’s movement and Women’s Studies?

Comparative analysis: some considerations

The above-mentioned countries were selected for inclusion in the study because they are theoretically interesting as their cultures and social structures vary greatly. Many are very much in the news these days (eg, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Uzbekistan and Eastern Europe) but accurate information about them is hard to come by. One of the principal aims of this volume is to see whether structural/cultural variations are related to variations in the nature and extent of the gender gap.

Most comparative studies focus on the similarities between countries. Our approach will also include, as suggested by Erik Allardt (1990), an explanation of cultural differences and unique historical developments characteristic of the individual countries.

Comparative studies have many inherent difficulties; these include lack of comparable information, variation in the quality and reliability of statistics and lack of uniform definitions of the factors and conditions included in the analyses. For example, higher education may be defined differently in different countries, academic degrees and ranks have different nomenclature and requirements and even substantive fields of study may not be uniformly structured. With the assistance of the authors we have attempted to define academic terminology and structures so that the resultant categories are homogeneous with respect to the factors considered, regardless of national, cultural or political variations.

Theoretical framework

Contemporary research on gender stratification in higher education has emphasized the structural characteristics of the university system (Chamberlain, 1988; Hicks and Noordenbos, 1990; Kyvik, 1988; Luukkonen-Gronow, 1987); the importance of individual motivation (Astin, 1984); cultural and societal barriers to the advancement of women (Acar, 1990; Cass et al., 1983; Lie, 1990); the influence (or lack thereof) of marital status on the productivity of female scientists (Cole, 1987; Cole and Zuckerman, 1987; Kyvik, 1990), and the interaction of cultural, social and personality factors on women’s professional careers (Acker et al., 1984; Harding, 1986; Stolte-Heiskanen et al., 1991). Most of the studies in this area have focused on individual countries. Notable examples of comparative studies include those done by Kelly and Slaughter, 1991; Lie and O’Leary, 1990; Moore, 1987; Stolte-Heiskanen et al., 1991; and Sutherland, 1985a.

Attempting to find a framework sufficiently broad to encompass situations in a wide range of countries and yet providing enough standardization to make meaningful comparisons possible, we decided to combine a comparative and integrative approach.

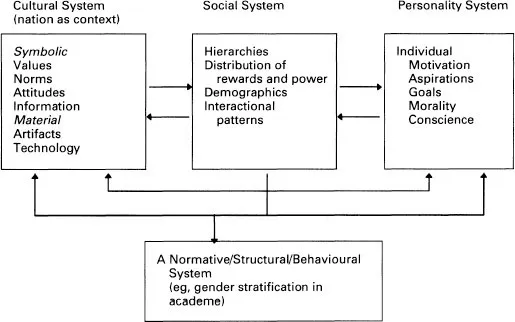

We were convinced, above all, of the centrality of the concept of culture in a paradigm which stresses the differentiation between culture, personality and society (Alexander, 1988). In our view the symbolic system (culture) provides a vital link between structure and action. (We owe a profound debt to Talcott Parsons, 1951 for this formulation.) In addition to a consideration of culture at the national level, we recognize that cultural sub-systems (eg, class, gender, religion) are also internalized. Although this process provides the background for the individual’s feelings, actions and thoughts, the individual is not a passive receiver. Each person negotiates a unique interpretation of the symbolic system, based on his or her own positions, abilities, interests and relational network.

Most observers would agree that any particular normative system generally furthers the interest of those holding power in that system. Therefore any discussion of the importance of culture must also include a consideration of power, which not only is inherent in normative systems, but also in social structures and interpersonal relations. Pierre Bourdieu’s (1988) analysis of the mechanisms whereby power is accumulated, maintained and legitimated is particularly relevant to the analysis of gender stratification within the university. Bourdieu maintains that the right to speak, ie, legitimacy, is granted to those possessing ‘cultural capital’ (recognized resources and values). Such individuals become spokespersons for the prevailing system and attempt to marginalize challengers and minimize their influence.

Although our theoretical framework appears to be two-dimensional, we are not presenting a static model in which homeostasis is the ultimate value. Rather it is clear to us that all three systems (cultural, social and personality) are constantly changing. Change may be stimulated by new circumstances, as in the case of invention, discovery and diffusion, or economic developments, and is also initiated by clashes of interest and the circulation of élites. Individuals involved in these processes are influenced by, and turn around and influence, their milieu. As Berger and Luckmann (1987) argue, human beings are products of society and at the same time society is a human product.

* The arrows refer to the influence of each category on the other, currently and over time.

Figure 1.1 Multi-dimensional model explaining inequalities in higher education

Even though we recognize the importance of sub-system categories, in this volume when we discuss culture we are referring primarily to situations in which the ‘nation is context’ (Scheuch, 1966). There are two primary aims in this regard. We wish to compare, across national boundaries, the relationship of selected factors (for example, political or economic patterns) to our dependent variable, and we also attempt to describe, within each country, the relative importance of the various institutions. The former is important if we are to have a meaningful framework within which to interpret our empirical information, the latter because we also need to know whether the priority accorded a particular institution itself becomes a significant independent variable.

Although a cultural system contains various ideational and material aspects, as indicated in Figure 1.1, these are largely derived from a core of values which provide the underlying inspiration. One of the most interesting by-products of our investigation has been the identification of core values in various countries and a description of their effect on higher education in general and on gender stratification in particular.

Discussing the social system, we refer essentially to the Weberian hierarchies of class (income), status and power. In addition to the emphasis on cultural background, we recognize that structure significantly affects historical processes and contemporary developments (Skocpol, 1979, cogently makes this point). Currently dramatic structural realignments have been occurring in many of the countries discussed in this volume. These structural changes have had profound effects in every area of life. We are particularly concerned with the effect of political, economic and religious changes on life in the university. Although these may appear, on the surface, to be gender neutral, in reality they often affect the lives of academic men and women in radically different ways.

At the level of the individual we are particularly interested in motivations, aspirations and goals and the behaviour which actualizes them. We view the individual as having internalized the fundamental norms and values of the relevant cultural contexts and interacting with significant others in terms of these guidelines. Each person, however, creates his or her own cultural synthesis, which is shaped by the individual’s needs and circumstances. We believe that most behaviour is goal-directed, although this does not necessarily imply that the goals are rationally selected or that the means employed to attain them are rational. Furthermore, we think that in some fundamental way human behaviour must be understood as each individual’s solution to the problem of adjusting to competing (and sometimes contradictory) goals while at the same time maintaining an acceptable ‘presentation of self’ (Goffman, 1959).

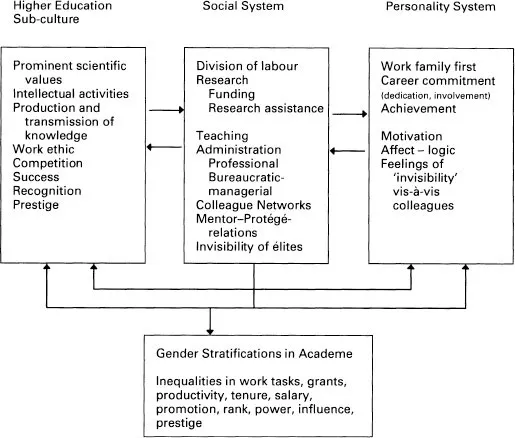

When Figure 1.1 is applied to our topic of gender stratification, the cells appear as in Figure 1.2.

The higher education sub-cultures in the countries under consideration may be descibed in terms of their universal and particularistic aspects. Universal values include rationality, intellectual activity and the search for and transmission of knowledge. These values (Bourdieu’s doxa) are so widely accepted and fundamental that they are rarely questioned. Particularistic aspects of the higher education sub-culture, by contrast, refer to values derived from the specific culture of the nation. Examples of these might include the stress placed on ‘serving the people’ in China, obedience to religious regulations in societies where these have been institutionalized, and the union of university and capitalist endeavours (eg, biotechnology) in many Western (and now also formerly Communist) countries.

Other values (which appear to be universal rather than particularistic) are more closely related to the behaviour of individuals. Bourdieu calls these constituents of the ‘scientific habitas’; they include such values as competition, prestige, the work ethic and recognition.

* The arrows refer to the influence of each category on the other, currently and over time.

Figure 1.2 Concepts related to gender inequality in higher education

The social system within the university (or research institute) is hierarchically organized. Advancement within the hierarchy is based on the accumulation of academic capital, primarily research productivity. Other criteria can also be important (eg, teaching ability, seniority, etc.), depending on the particular institution and the country in which it is located.

Generally, academic personnel at universities divide their time between research, teaching and administrative tasks. The emphasis and extent of these tasks often vary within and between countries. For instance, countries under the influence of the former Soviet Union have organizational patterns in which research is primarily concentrated in Academies of Science and teaching is the main function of universities. A similar division of labour is also found in France, where CRNS has developed as a centre of research.

In some countries (mainly in the West) academics themselves control advancement within the hierarchy. In others the state, whether for religious or political reasons, makes the major decisions. (See Hojjat, Mak and the chapters concerning former Communist countries in this volume.) In all countries the distribution of resources such as funding for research and research assistance is being decided increasingly by outside sources including foundations and quasi-governmental agencies such as UNESCO and the World Bank. Even in these situations, however, the distribution of resources is mediated by recommendations from influential academics. Individuals also may gain power and influence within an informal network of colleagues. Usually, but not always, these networks are organized according to discipline. Within disciplines different schools of thought often arise which compete for power and legitimacy. Side by side with the professional structure is the bureaucratic-managerial (administrative) structure, which controls the operational and support aspects of the institution. Recruitment into the entire system is controlled by the award of advanced degrees and mentor-protégé relationships.

The university has been described as a ‘greedy institution’ (Acker et al.,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: National profiles

- Part 3: Conclusion

- Statistical appendix

- Biographical notes on contributors

- Bibliography

- Index