- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Impact of Hazardous Waste on Human Health

About this book

The author of Impact of Hazardous Waste on Human Health is a public health official with the unique perspective that only insider status can provide. His book is intended for policy makers, environmentalists, toxicologists, public health officials, academic personnel, and health care providers.

The author addresses six themes: hazardous waste issues must be more vigorously examined, site remediation is critical, risk management must extend beyond waste site clean up, disease prevention must be a priority, interagency partnership is mandatory, and the best technology must be applied.

Johnson also considers the pros and cons of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) also known as the "Superfund." His years of experience with this law, and countless other issues related to hazardous waste, make Impact of Hazardous Waste on Human Health an important and positive contribution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Impact of Hazardous Waste on Human Health by Barry L. Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Chemical & Biochemical Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Nature and Extent of Hazardous Waste

How many uncontrolled hazardous waste sites are there in the United States and what will be the cost of their remediation (i.e., cleanup)? What are the broad characteristics of these sites, and where does the public rank the health hazard of hazardous waste sites? Moreover, what is meant by hazardous waste and public health in the context of this book? This chapter addresses these questions and introduces CERCLA and RCRA, the two key federal statutes on waste management.

Industrial development and modern agricultural practices have both contributed mightily to human advancement and well-being. The former serves as the engine for modern national economies; the latter is essential for producing food and fibers. It can be argued that advances in industrialization and agriculture have improved the quality of life, including the public’s health. For instance, post–World War II industrialization in the United States produced the pharmaceutical industry, which, in turn, has produced an abundance of drugs essential for treatment or prevention of human disease. Moreover, industrialization has led to development and production of consumer products that make work easier and safer. Similarly, agricultural improvements have increased food production in many parts of the world, with obvious benefits for human health.

However, both industrial development and modern agriculture have undeniably harmed environmental quality and ecosystem integrity. One significant adverse effect is the generation of waste. Waste is defined as a by-product that is deemed useless or worthless by the discarder. By this definition, chemicals discarded into the environment are a form of waste. Some effects of environmental contaminants on human health and ecosystems are relatively well understood; others are still being investigated and debated. For example, the association between vehicle exhaust and ambient air pollution is well-known, including the deleterious release of lead from leaded gasoline into the environment and its effect on human health as lead accumulates in the body.1 Less well understood is how chlorofluorocarbons contribute to the reduction of ozone in the atmosphere, leading ultimately to a predicted increase in the incidence of skin cancer (NRC, 1991a; Rom, 1992).

Some agricultural practices have also contributed to environmental degradation and damage to ecologic systems. For example, excessive reliance on chemical fertilizers increased levels of chemical contaminants in groundwater and surface water in some areas of the United States. Another example is the effects on ecologic systems of DDT from past agricultural, consumer, and public health uses (e.g., mosquito control). DDT reduced the numbers of some wild birds through eggshell thinning. A contemporary controversy concerns the effects on the global environment as rain forests are destroyed for conversion into cropland. These examples, and others that could be cited, show that agricultural practices, if not adequately evaluated for their ecologic effects, can seriously damage the environment and ecologic systems.

Modern industrial societies produce a multitude of products intended for consumption. Indeed, consumerism fostered by free enterprise undergirds national economies in many countries. The production and distribution of consumer goods has brought many benefits to individual consumers; for example, products such as video equipment used for education and entertainment can improve the quality of life. But these positive contributions have come with some deleterious effects. One such effect is the environmental impact of increased waste generation. Discarded consumer products soon become waste that requires disposal. In 1988, each person in the United States produced about four to five pounds of waste per day (PHS, 1990; Plotzman, 1992). Household waste adds to the municipal waste stream. More than 50,000 tons of waste are produced each day in Los Angeles County, California. Figures available for several industrial countries show a pattern similar to that in the United States—large amounts of waste produced per person per year (Plotzman, 1992).

Studies conducted by the University of Arizona have produced a comprehensive database on residential waste. Detailed characterization of household hazardous waste showed that 11 million hazardous waste items were generated by the approximately 120,000 households in Tucson, Arizona (Wilson and Rathje, 1989). They also collected curbside household waste in Tucson and Phoenix, Arizona; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Marin County, California. The household hazardous waste fraction ranged between 0.42 and 0.61% of the refuse weight. The investigators noted that residential waste sent to landfills may contain higher concentrations of hazardous materials than does commercial waste.

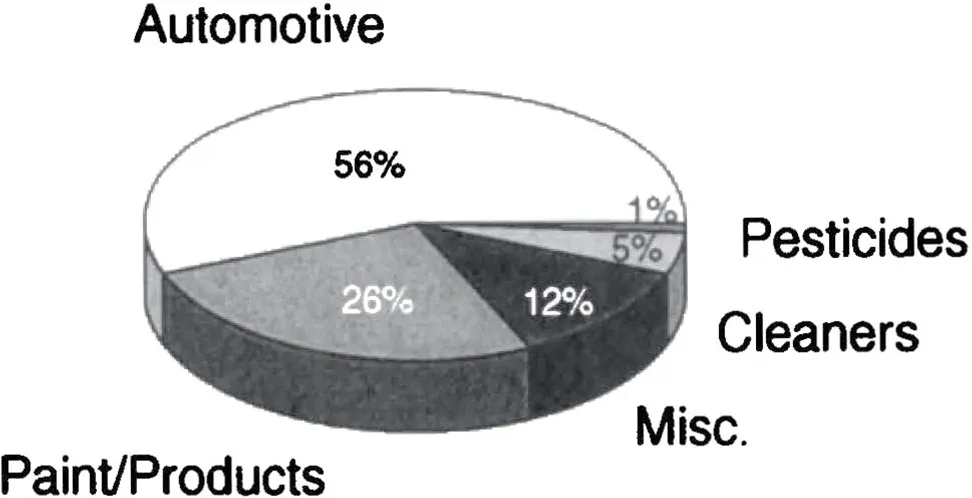

The kinds of hazardous materials discarded in household waste and the householders’ knowledge about hazardous waste management were studied in two counties in Arizona (Wolf et al., 1997). Telephone and face-to-face interviews with residents about their hazardous waste practices were conducted in Pima and Maricopa counties, Arizona. The results indicated residents were improperly disposing of significant amounts of household hazardous waste. Of note was that although Pima County had a household hazardous waste program and public awareness support, only 5% of the population participated. The investigators grouped hazardous materials in household waste for 1995–1996 into five categories, shown in Figure 1.1.2 The category automotive includes batteries and antifreeze. Two categories, automobile and paint/paint products, represented more than 80% of household hazardous waste. The investigators concluded that household hazardous waste programs must be supplemented by strong educational programs, including how the waste can cause adverse effects on human health and the environment.

Figure 1.1. Household hazardous waste by weight in Pima County, Arizona, 1995–1996 (Wolf et al., 1997).

Improper disposal of common household waste can cause health problems by, for example, creating noxious smoke from burning trash or providing breeding grounds for vermin. In addition, hazardous substances in municipal waste released from landfills or other methods of waste disposal can contribute to air, water, and food-chain pollution. Releases of hazardous substances from hazardous waste sites into groundwater can significantly threaten drinking water supplies. To reduce the amount of household waste produced per household will require greater efforts in recycling, biodegradable packaging for consumer products, and changes in personal lifestyles.

Modern economies are built on both industrialization and agriculture, with benefits that accrue from both. But environmental degradation, with consequent implications for human health and ecologic systems, has accompanied this development. In some sense, the old cliche “Haste makes waste” applies here. Hazardous waste left expediently in the environment because it was often inexpensive to do so has now become a major concern. What is the basis for this concern and what does it mean for human health and its impact on ecologic systems? Some background about the two major U.S. statutes on hazardous waste management will be helpful.

CERCLA AND RCRA

In the 1970s, discoveries of toxic substances in communities at Love Canal, New York and the “Valley of the Drums” in Kentucky, and a chemical plant fire in Elizabeth City, New Jersey, among others, riveted the attention of the U.S. public and galvanized legislative action. Hazardous waste and its presence in residential environments became a concern of environmentalists, legislators, and public health officials alike. The legislative outcome was the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA), quickly christened the Superfund Act, after the multibillion-dollar Hazardous Substance Superfund created by the act.

The Hazardous Substance Superfund3 is a trust fund held by the U.S. Treasury and funded by taxes on select parts of private industry: petroleum excise taxes, a chemical feedstock tax, a corporate environmental tax, general revenues, and other sources (Probst, 1992). Ultimate responsibility for the fund rests with the U.S. Congress. Appropriations from the trust fund are made annually to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for administration. This budget appropriation to the EPA funds CERCLA’s directives of identifying uncontrolled hazardous waste sites and sites where emergency spills have occurred, protecting the public’s health and environmental media from the effects of releases from identified sites, and remediating (i.e., cleaning up) those sites that merit such action. That same budget appropriation to the EPA contains funds for CERCLA mandates to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and a program of basic research and worker training for site remediation workers administered by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

The word Superfund is sometimes used to refer to both the CERCLA statute and the Hazardous Substance Superfund. However, in the context of this book, CERCLA will be used exclusively to describe the statute and programs of the same name.

The CERCLA statute of 1980 contains what is called a “sunset clause,” which is a legislative device that sets a time limit on a specific law. The sun sets on the statute after a prescribed passage of time, unless Congress continues the law through reauthorization. For CERCLA, this time limit is five years. Reauthorization means that Congress takes action to extend a law’s authorities and mandates. This process usually involves congressional hearings, debate, and ultimately, a vote to extend or terminate the law under consideration. In 1986, Congress reauthorized CERCLA, but with substantive changes through various amendments to the 1980 statute. In 1991, Congress voted simply to extend CERCLA, as amended in 1986, for another five years. As of this writing, CERCLA has not been reauthorized again, but the EPA has made several changes in how it administers various parts of the statute.

At the heart of CERCLA is the philosophy, evidenced by enforcement powers given to the EPA, to hold accountable those parties responsible for the consequences of hazardous substances released into the environment from uncontrolled hazardous waste sites. As noted in the Preface, CERCLA is a federal environmental law without parallel in its controversy. Much of the controversy derives from the “polluter pays” philosophy, because parties can be held liable for costs they may deem inappropriate or excessive.

Opinion is widely divided on CERCLA’s importance for protecting human health and remediating environmental contamination. Because CERCLA was enacted by Congress primarily from concern that substances released from uncontrolled waste sites were causing cancer and other dire health problems, some of the controversy attending CERCLA gets voiced as issues of human health. The 1986 congressional debate over CERCLA’s reauthorization illustrates the polar extremes of view on issues of health:

On this point we should be absolutely clear. Uncontrolled releases of hazardous substances present a very real threat to the public health. Superfund is the way to clean up the contaminated water and soil so that our children do not become ill from toxic chemicals (Senator George Mitchell, 1986).It is time to move faster, to rid our environment of the toxics that are poisoning our land and water, and threatening our citizens (Senator Frank Lautenberg, 1985).As a matter of fact, at this moment I honestly do not know if there are any victims of diseases caused by exposure to releases from Superfund sites (Senator James Abdnor, 1985).

The opinions quoted probably reflect similar polar differences of view between segments of private industry and environmental organizations about hazardous waste as an environmental health problem. (Environmental health is used here to denote the area of public health that is concerned with effects on human health of socioeconomic conditions and physical factors in the environment.) These differences will narrow as scientific information and experience accrue. It is hoped that the information in this book will contribute to a better base of technical information on the costs and benefits of the CERCLA statute.

Distinct from CERCLA, which covers uncontrolled hazardous waste sites, is the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), which pertains to the permitted, controlled management of hazardous and solid wastes. RCRA is the federal statute that regulates waste generators, waste transporters, and waste management facilities. RCRA began as an amendment to the Solid Waste Disposal Act in 1965, was enacted into law in 1976, and was amended in 1980 and 1984. Sites covered by RCRA include landfills, waste piles, s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Preface

- The Book’s Structure and Themes

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Nature and Extent of Hazardous Waste.

- Chapter 2. Public Health Assessment.

- Chapter 3. Exposure Assessment.

- Chapter 4. Toxicology of CERCLA Hazardous Substances.

- Chapter 5. Human Health Studies.

- Chapter 6. Workers’ Health and Safety.

- Chapter 7. Health Promotion.

- Chapter 8. Risk Communication.

- Chapter 9. Environmental Equity.

- Chapter 10. Comparative Risk Assessment.

- References

- Initialisms

- Glossary

- Index