- 7 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Orchids of Nigeria

About this book

This text includes a description of 104 species with 195 photographs. It also contains a checklist of Nigerian orchids.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Orchids of Nigeria by L.B. Segerback in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

General characteristics

The orchids, or Orchidaceae, form a very large family of plants. It has the largest number of species – about 25 000 are known – and is represented in all the continents except Antarctica. As the members are found all over the world, growing in widely different climates, considerable diversity is to be expected within the family.

The photograph in figure 1 shows a small Leucorchis which can be found on the coast of Greenland in the Arctic Ocean. Figure 3 is of a large African Angraecum. Despite the many apparent differences, these two plants have certain, easily recognizable features in common – and in common with all other orchids, see figure 4 which shows the variation in shape in some African orchids.

THE FLORAL PARTS

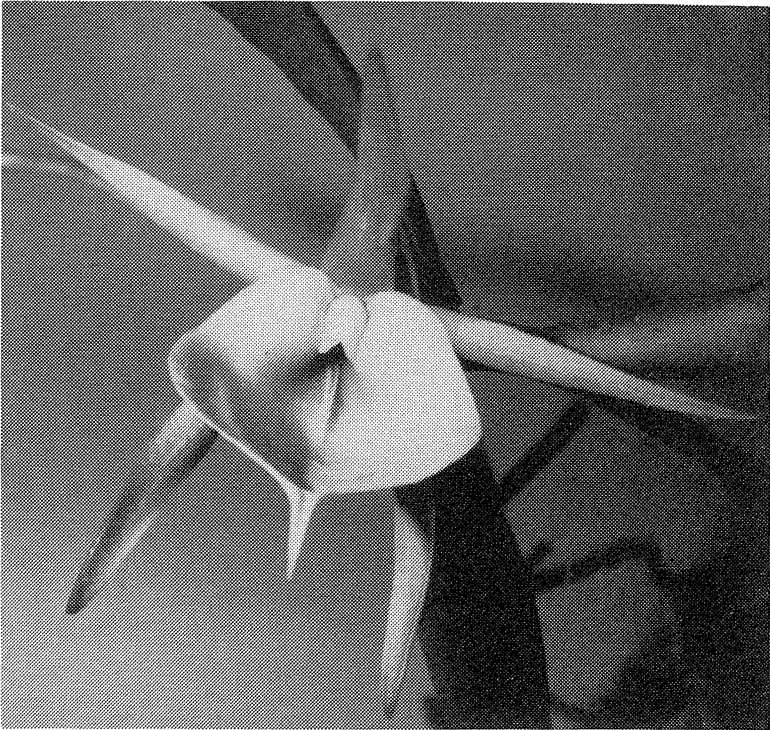

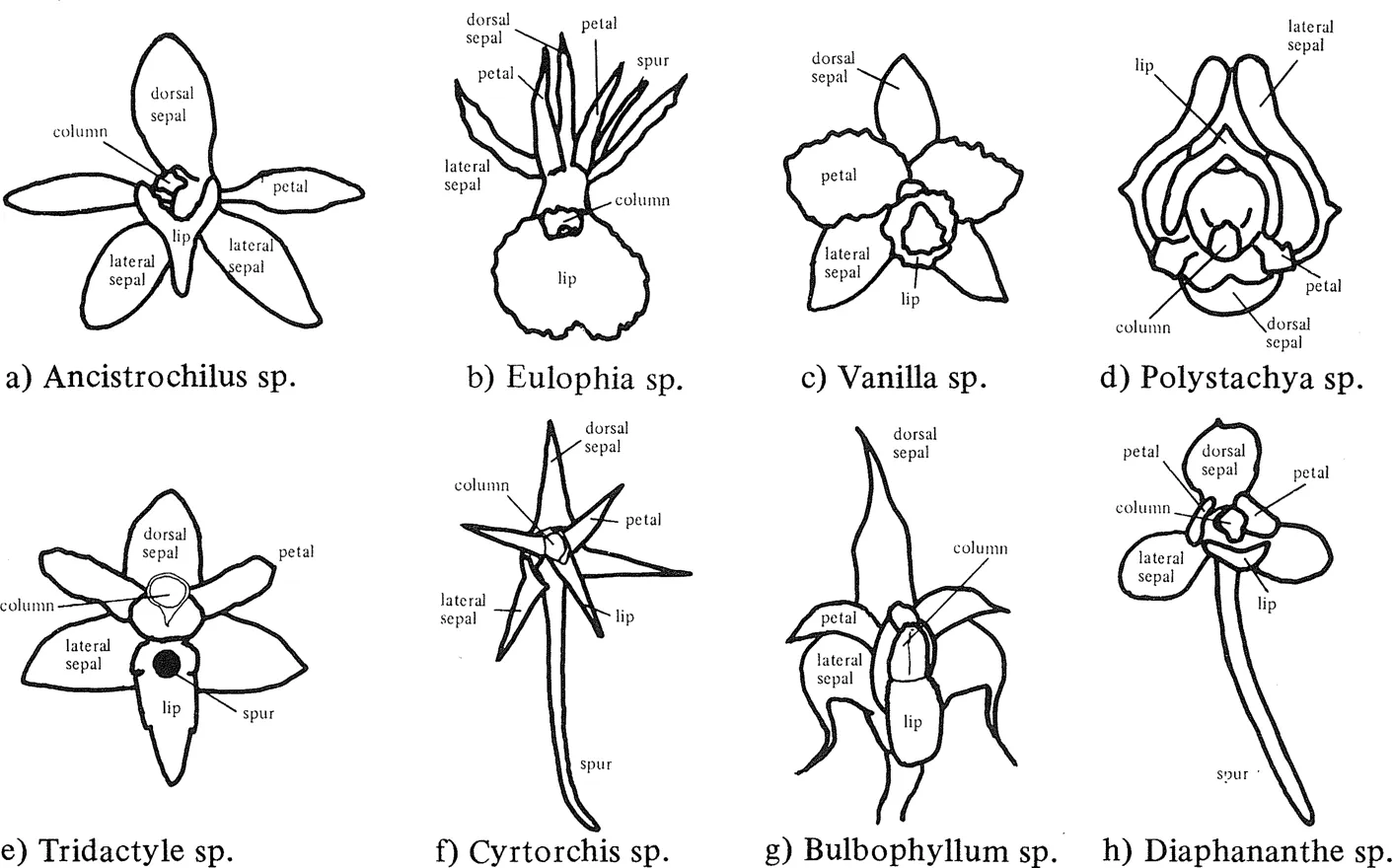

The orchid perianth consists of six segments, arranged in two whorls of three – the outer sepals and the inner petals. In some African genera, such as Cyrtorchis, figure 4f, all the segments can look the same. In such a case, the term tepal is used to denote both sepals and petals. However in general one segment of the inner whorl (the petals) is very different from the others.

This segment is called the lip or labellum. It is often brightly coloured, spotted, or provided with streaks, ridges, hairs or frills. The rear part of the lip is sometimes drawn out to form an often nectar-filled spur, as in figure 4f and 4h. This can be quite long in some species – 20 cm or more. The segment of the outer whorl opposite the lip, the dorsal sepal, is also frequently different in size and shape from the paired lateral sepals.

Another distinguishing feature of orchid flowers is the special organ called the column. This is unique, being the union of the male and female reproductive organs, see figure 5.

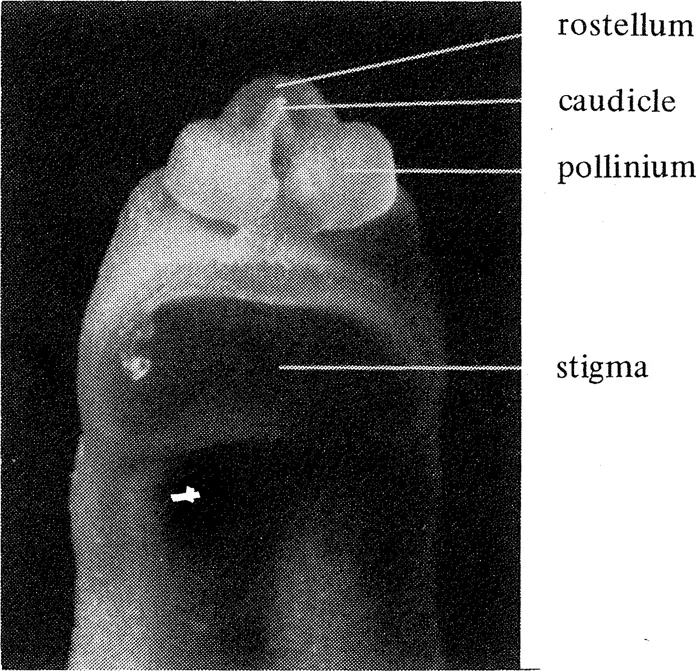

At the tip of the column there is usually the anther, the male reproductive organ. This often has an anther cap or operculum, a little lid which, when pushed aside or lifted, reveals the pollen, see figure 6. In orchids, the pollen grains are generally stuck together to form a discrete number of club-like masses known as pollinia. Each pollinium is attached to the rostellum by a stalk (the caudicle or stipes) which ends in a sticky disc, the viscidium.

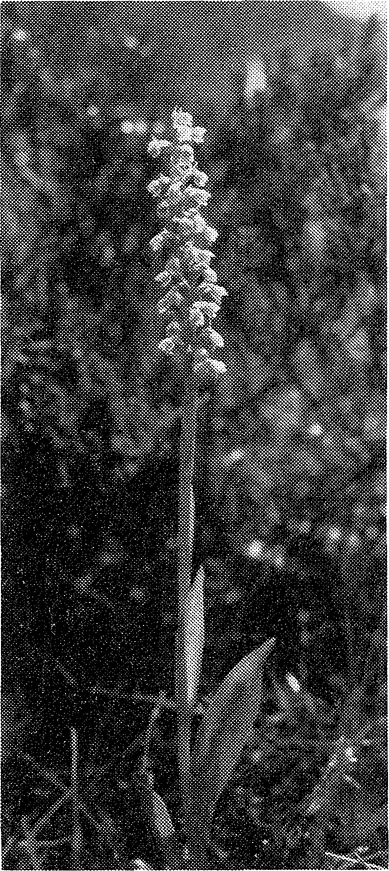

Fig. 1. Leucorchis albida.

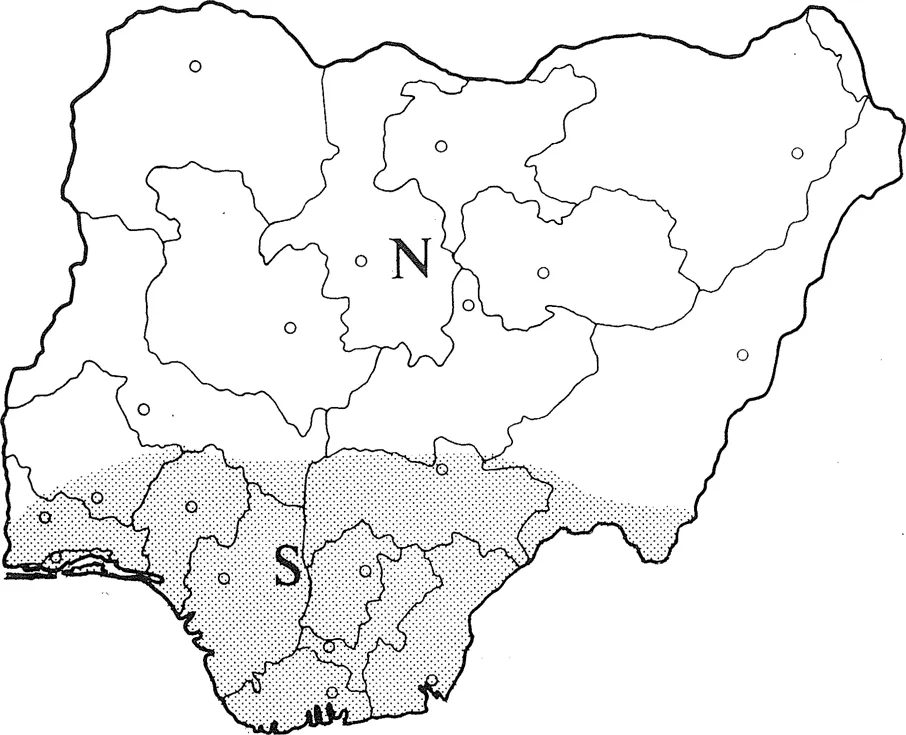

Fig. 2 (above left). The division of Nigeria in this book into a northern (N) and a southern (S) part coincides, grosso modo, with the division between rain forest, in the south, and savanna in the north.

Fig. 3 (above right). Angusæcum birrimense.

Fig. 4 (centre). Floral parts of different types of African orchid flowers.

Fig. 5 (below left). Flower of Eulophia cristata, with one lateral sepal removed to show the column.

Fig. 6 (below right). The top of a column.

REPRODUCTION IN ORCHIDS

Pollination is by insects.* When one works its way into the flower to find nectar, the viscidium sticks on to its head or body. In this way, a whole pollinium will be transferred to the sticky stigma of another flower.

Generally there are two stigmas. These are found on the column below the anther, separated from it by the rostellum. (In fact this is a third stigma, but a sterile one.)

The fruit is nearly always a capsule. In most species, as the flower develops, the ovary turns 180° round its axis, a phenomenon known as resupination. This has the result that in these species, the lip comes to lie at the bottom of the flower. An important exception is the genus Polystachya, see pages 47 to 57.

The seeds are very small and very many. Orchid seeds are normally spread by the wind, and they are very light. In fact they contain no endosperm. As this is the substance that provides food for seedlings, growing orchids from seed is difficult. The difficulty is increased by the fact that the embryo can grow only when `infected’ with a kind of fungus.

Most orchids do not need this fungus once they have started to grow. However with a few there is life-long dependence. This is the case with some orchids which have little or no chlorophyll. These plants known as saprophytes can be seen growing in the heavy shade of the floor of the rain forest. They are brownish or yellowish in all parts; their leaves are no more than scales. An example is Auxopus, discussed on page 29.

We have seen that most orchids are pollinated by insects. Some have aids that attract insects. For instance there are genera with flowers that look like the females of certain species of insects and this attracts the males, see figure 7. Other orchids are scented. However a smell that insects like may not always appeal to us! Thus there are several species of the genus Bulbophyllum with a rather unpleasant smell like that of dead animals.

It is believed that the Orchid family, although very large, is quite recent in origin. Certainly in some ways there is evidence of an ongoing evolution process. Thus it is easy to create new hybrids. This is often done in commercial horticulture. Also many existing species seem to be rather unstable. Of course this sometimes makes the classification of orchids very difficult.

TERRESTRIALS AND EPIPHYTES

If we use the habitat as the basis of classificaton, we find that there are two groups of orchids in tropical Africa. These are the terrestrials and the epiphytes.

Terrestrial orchids root in the earth, from which they get water and minerals, see figure 8. Usually they rest and wither during the dry season. All the orchids of temperate climates are terrestrial.

The epiphytes grow on trees, see figure 9. Often they are found high up in the crown where they can obtain a lot of light. However some prefer the lower, deeply shaded branches of trees in the tropical rain forest. Epiphytes have roots to hold them where they grow, and also free (or aerial) roots. The main use of the latter is to get moisture from the air.

Fig. 7 (above left) Ophrys apifera, an orchid from Spain, with insect-like flowers.

Fig. 8 (about right). Eulophia cristata, a terrestrial orchid.

Fig. 9 (centre). An epiphytic orchid: Cyrtorchis arcuata.

Fig. 10 (below). An orchid with pseudobulbs: Bulbophyllum sp.

It is important to note that epiphytic orchids are not parasites – the trees on which they grow give them no food, only support. (Strictly speaking, though, the orchids are parasites in relation to the fungus necessary for the germination of the seeds.) The minerals that the epiphytes need are provided in the water that runs down the bark when it rains. Clearly this is a limited source of nourishment, so these plants grow rather slowly.

The roots of epiphytic orchids generally have...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Chapter 1: General characteristics

- Chapter 2: Nigerian orchids, terrestrials

- Chapter 3: Nigerian orchids, epiphytes

- Chapter 4: Botanical glossary

- Check-list of Nigerian orchids by C.Z.Tang & P.J.Cribb

- Bibliography

- Index to plants mentioned in the text