- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Biotechnological Approaches in Food Adulterants

About this book

The book highlights the biotechnological advancement in the area of food adulterants and outlines the current state of art technologies in the detection of food adulterants using omics and nanobiotechnology.

The book provides insights to the most recent innovations, trends, concerns, and challenges in food adulterants. It identifies key research topics and practical applications of modern cutting-edge technologies employed for detection of food adulterants including: expansion of food adulterants market, potential toxicity of food adulterants and the prevention of food adulteration act, cutting-edge technology for food adulterants detection, and biosensing and nanobiosensing based detection of food adulterants. There is need for new resources in omics technologies for the application of new nanobiotechnology. Biotechnological Approaches in Food Adulterants provides an overview of the contributions of food safety and the most up-to-date advances in omics and nanobiotechnology approaches to a diverse audience from postgraduate students to researchers in biochemical engineering, biotechnology, food technologist, environmental technologists, and pharmaceutical professionals.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Overview of Food Adulteration from the Biotechnological Perspective

Emails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]

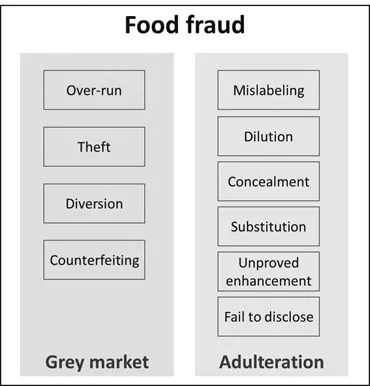

1. Food Fraud and Food Adulteration

| Type of Food Fraud (Defined and Collected by Global Food Safety Initiative, GFSI) | Definition (from Safe Secure and Affordable Food for Everyone Organization, SSAFE) | Examples (from GFSI Food Fraud Think Tank) | General Type of Food Fraud |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dilution | “The process of mixing a liquid ingredient with high value with a liquid of lower value.” |

| Adulterant-substance (Adulterant) |

| Substitution | “The process of replacing an ingredient or part of the product of high value with another ingredient or part of the product of lower value.” |

| Adulterant-substance or tampering |

| Concealment | “The process of hiding the low quality of food ingredients or product.” |

| Adulterant-substance or tampering |

| Unapproved enhancements | “The process of adding unknown and undeclared materials to food products in order to enhance their quality attributes.” |

| Adulterant-substance or tampering |

| Mislabelling | “The process of placing false claims on the packaging for economic gain.” |

| Tampering |

| Gray market production/ theft/diversion | Outside scope of SSAFE tool. |

| Over-run, theft, or diversion |

| Counterfeiting | “The process of copying the brand name, packaging concept, recipe, processing method, etc. of food products for economic gain.” | “Copies of popular foods not produced with acceptable safety assurances” | Counterfeiting |

| Ingredient | No. Records | No. Incidents | No. Inferences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy products | ||||

| Milk (Fluid, cow) | 184 | 48 | 136 | |

| Milk (Fluid, goat) | 21 | 0 | 21 | |

| Milk powder | 45 | 8 | 37 | |

| Beef meat | 84 | 28 | 56 | |

| Beef (grounded) | 20 | 5 | 15 | |

| Chicken meat | 27 | 13 | 14 | |

| Sheep meat | 22 | 0 | 22 | |

| Lamb | 19 | 11 | 8 | |

| Cooking oils | ||||

| Olive oil (extra virgin) | 76 | 20 | 56 | |

| Olive oil (other than extra virgin) | 36 | 8 | 28 | |

| Other edible cooking oil | 21 | 14 | 7 | |

| Camellia seed oil | 23 | 0 | 23 | |

| Sesame oil | 18 | 2 | 16 | |

| Ghee | 26 | 16 | 10 | |

| Spices | ||||

| Chili powder | 39 | 19 | 20 | |

| Turmeric | 32 | 15 | 17 | |

| Beverages and drinks | ||||

| Alcoholic beverage | 25 | 23 | 2 | |

| Liquor (unspecified) | 16 | 13 | 3 | |

| Whisky | 22 | 14 | 8 | |

| Vodka | 42 | 35 | 7 | |

| Coffee and confectionaries | ||||

| Coffee (Arabica) | 24 | 1 | 23 | |

| Honey | 84 | 17 | 67 | |

2. Types of Food Adulteration

2.1 Substitution

2.1.1 Products of Plant Origin

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- 1. Overview of Food Adulteration from the Biotechnological Perspective

- 2. An Overview of Potential Toxicity of Food Adulterants and Food Adulteration Act

- 3. Advances in Technologies used in the Detection of Food Adulteration

- 4. Food Colours: The Potential Sources of Food Adulterants and their Food Safety Concerns

- 5. Innovative and Emerging Technologies in the Detection of Food Adulterants

- 6. Contributions of Omics Approaches for the Detection of Food Adulterants

- 7. Advances in Proteomics Approaches for Food Authentication

- 8. Contributions of Fingerprinting Food in the Detection of Food Adulterants

- 9. Nanosensors as Potential Multisensor Systems to Ensure Safe and Quality Food

- 10. Global Perspective of Sensors for the Detection of Food Adulterants

- 11. Application of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology in Advancement of Safety Issues of Foods

- 12. Computing in Biotechnology for Food Adulterants

- Index