CHAPTER 1

Necessity and Invention in Counselling

Suzie” had experienced five suicide attempts.1 Her previous therapist said the seventeen-year-old had been compliant with treatment but remained “high risk.” She obtained elevated scores for low self-esteem, anger, suicide ideation, and depression on a standardized measure of suicide probability administered during our first session.

I attempted to normalize some of Suzie’s experiences and reframe others so as to place responsibility on the perpetrator of emotional and physical abuse (her father) and to help her see herself as a competent actor and increasingly able problem solver over time. We co-developed behavioural “homework” assignments that included positive affirmations, meaningful and enjoyable activity, regular physical activity, and reality testing to discover the accuracy (or inaccuracy) of perceived slights from teachers, family, and peers. I had her retell her “story” with suggested amendments to engender hope. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) was used to deal with specific instances of childhood trauma. Suzie participated in all suggested activities, but her increasing levels of distress led me to conclude the methods we were using were not being effective. A re-referral at this point would have further accentuated the youth’s sense of hopelessness, so with an affected air of assurance, I suggested that we create a map of her self to find what was keeping her from responding to treatment.

Mapping and Modifying the Self of a Client in Therapy

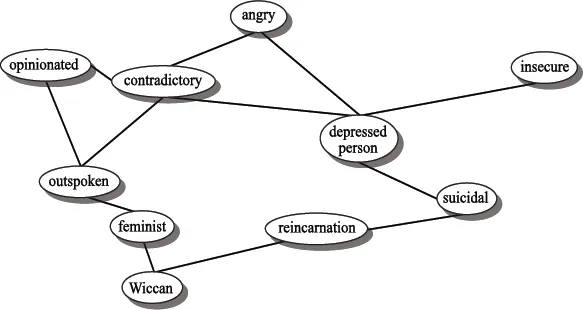

Viewing the self as a representational cultural construct (Blustein & Noumair, 1996; Dennett, 1995; Mead, 1912/1990; Shotter, 1997), I asked Suzie to prioritize four lists: 1) self-defining roles, 2) qualities she liked about herself, 3) changes she would make to herself if she could, and 4) things she believed to be true. Each unit of self-representation represented a small unit of culture. Following the lead of Dawkins (1976), I called these elemental units “memes.” In the physical world, the existence of nuclear, electromagnetic, or gravitational forces leads to a structuring of matter, so I looked for analogous mental forces that could similarly result in mental structures. Shared affective, behavioural, and connotative characteristics present as forces of attraction. For example, a meme given the title “heart-shaped boxes” was associated, in the client’s mind, with romantic love, and an “attractive force” was represented as a line connecting the two in figure 1.1. She experienced wistfulness coupled with feelings of emptiness and loss associated with these boxes, which she collected and displayed. I viewed this behaviour as a dramatic expression of her associated emotions, so the meme was linked to another labelled “dramatic person.” By linking memes sharing connotative, affective, or behavioural dimensions with those prioritized by the client as more difficult to change closer to the centre, the self-structure pictured in figure 1.1 emerged.

Some readers will recall that grunge rock artist Kurt Cobain committed suicide in 1994 after recording a song titled “Heart-Shaped Box.” Given Suzie’s worldview, Goth-like appearance, and taste in music, it is likely she was influenced by this recording, but in adopting the meme, she necessarily gave it her own interpretation. Suzie also made a connection with popular culture in reporting that she compulsively rereads The Bell Jar, a book about a depressed and suicidal youth; the book title is represented in figure 1.1 as a self-identifying meme connected to memes labelled “suicidal” and “writer.”

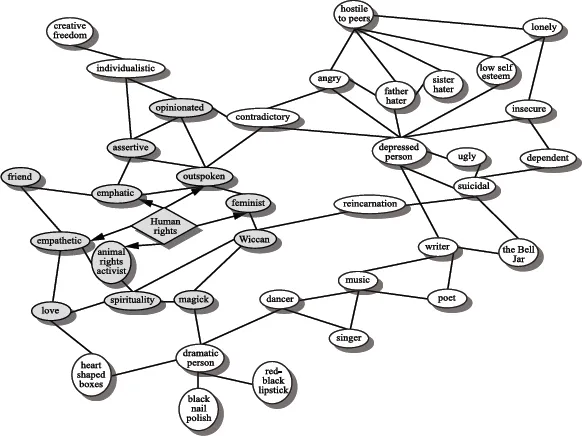

The meme labelled “depressed person” forms a hub or core connected to eight other memes, such as “ugly,” “suicidal,” and “father hater.” Rumination may be predicted once consciousness is focused on this depressive cluster since the number of cognitive pathways to other parts of the self is limited. Figure 1.2 illustrates this ruminative cycle.

This client’s cognitions could begin at any point along the paths reproduced in figure 1.2 and lead to suicidal thoughts. A feedback loop is illustrated leading from “dependent” to “insecure” to “depressed person” and returning to “suicidal.” Rumination is thus circular, leading to increased client distress. While the most common pathway to suicidal thoughts is through depression, an alternate route leading from the client’s beliefs in Wicca to reincarnation to suicide ideation is also illustrated.

FIGURE 1.1. Initial self-map of Suzie with edges between memes representing shared connotative, affective, or behavioural dimensions.

FIGURE 1.2. An illustration of memetic self-map paths or routes leading to suicide ideation in the self of “Suzie.”

Sequentially linked memes, as illustrated above, may be viewed as cognitive scripts leading to patterned behaviours within an overarching self-defining narrative. The self that is the protagonist in such narratives may be mapped so as to identify and graphically represent internal relationships and thematic possibilities. Returning to the total representation in figure 1.1, it can be seen that the removal of “depressed person,” “suicidal,” and “angry,” without first preparing alternatives, would lead to fragmentation of the self as pictured. Operating on the assumption that most people, especially those who are depressed or suicidal seek self-stability (De Man & Gutierrez, 2002), I recommended that Suzie restructure her self in some ways before focusing on removing her depression and suicide ideation identifiers.

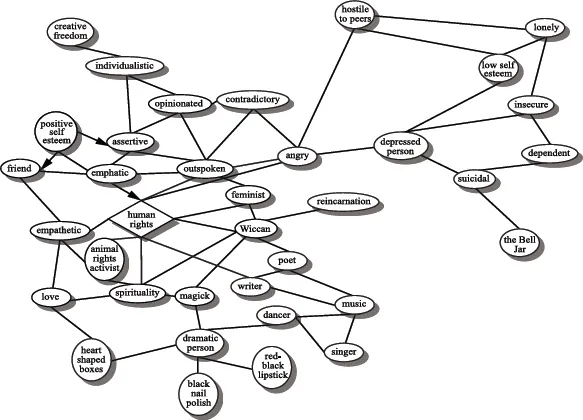

The meme “animal rights activist” in figure 1.1 was an earlier reframe of angry client behaviour associated with perceived cruelty to dogs and cats. Although animals are not human, we used this meme to inspire and inform a new thematic core, “human rights,” in figure 1.3. That new meme included a behavioural injunction to fight for social justice.

The preparation of a new core meme involved examining, and in some cases reframing, those memes already present. Suzie had challenged teachers and other adults over the rights of children and youth, which resulted in her seeing herself as “outspoken.” She believed that females generally suffered from sexism, and she embraced feminism. She believed that the Christianity of her parents was oppressive, and she embraced an alternative religious belief system (Wicca). She described herself as emphatic and empathetic.

Established memes were conscripted to support the new persona. For example, she had written prose and poetry focusing on her depression, and she read books that reinforced a negative and pessimistic view of life. With this new human rights shift, she began to read material that supported her views about animal, children’s, and women’s rights, and about her emerging views on spirituality. With encouragement, she began to write poetry and prose in support of her passionately held beliefs. She published some of her writings in a student newspaper and was surprised by the positive regard she was given by peers. Her anger, which had been directed inwardly, reinforcing her depressive and suicidal self-representations, now became increasingly focused externally in the service of social interest. These changes are represented in figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.3. A revised memetic self-map of a suicidal youth showing the location of a co-

constructed new meme, “human rights,” with supporting memes tinted in grey.

FIGURE 1.4. Self-map illustrating changes in self-definition resulting from “homework assignments” designed to support the new core meme “human rights.”

Suzie developed a plan to move in with an aunt in a neighbouring community. She found that her writing, which still had an anti-establishment flavour, was accepted by a new group of friends with similar views. She began dressing differently and discovered that she was considered attractive. The meme “hostile to peers” withered and then disappeared. Suzie’s mother and sister followed her in leaving her father, who at one time loomed quite large in her life, though now appeared as a pathetic derelict who could not take care of himself. Suzie lost much of her anger, but a level of disgust remained. She now saw herself as empowered to positively affect her future.

Over the course of about seven months, the new core we had developed became increasingly central to Suzie’s self-definition, while those memes supporting her “depressed person” meme became fewer in number. We were then able to eliminate “depressed person” from her identity and reframe depression as an emotional state that we may sometimes experience without it defining who we are. She subsequently scored within the nonclinical range on a standardized test for suicide risk, and therapy was terminated. Suzie’s mother called a year later to say that her daughter was doing very well socially and academically.

The method of preparing memetic self-maps described here may be understood using a branch of mathematics called Graph Theory (Robertson & McFadden, 2018). In GT the units represented in ovals (memes) would have been called “vertices” or “nodes.” Connecting lines are called “edges” or “arcs.” Proximity between memes gave the sense of greater attraction, and with GT it would be possible to quantify that attraction using edge line weight. In figure 1.1 we saw that the meme “depressed person” is connected to eight adjoining memes (in GT, degree = 8), supporting its designation as a core of the self-structure. As we saw in figure 1.2, sequential patterning can be observed between proximate memes with routes identified for habitual thoughts. Seen through the lens of GT, memetic self-mapping is a mathematical way of visualizing a naturally occurring phenomenon. As we shall see, it is also compatible with various heretofore competing lenses within the discipline of psychotherapy.

The Call of This Research

Notions of self-concept, self-esteem, self-actualization, and self-validation predominate in psychology, yet the core concept to which these constructs refer is less well understood. Eric Erikson wrote, “The ability to form intimate relationships depends largely on having a clear sense of self” (2003, p. 98). William Bridges (1980, 2001) tied his theory of adult transition to changes in this “self.” The self was one of four pillars that Schlossberg, Waters, and Goodman (1995) used to understand how individuals cope with life transitions. According to Seigel (2005), the self “distinguishes you or me from others, draws the parts of our existence together, persists through changes, or opens the way to becoming who we might or should be (p. 3).”How do we come to have a particular understanding of our selves? What keeps selves sufficiently stable that they are recognizable to their “owners” and others? If it is a matter of belief, why is it difficult to change unwanted aspects of the self? To what degree did the mapping exercise contribute to the successful outcome in Suzie’s case?

The idea of self as used here is intertwined with the notion of culture. We are defined according to information provided by our families, friends, communities, and society in conceptual units learned within our cultural milieu. Mapping the self is thus a relational activity concerned with both internal structure and external influences or determinants.

Readers will recall that Suzie was asked to prepare and prioritize four lists of self-descriptors. Memes were defined as having an affective dimension. Was this dimension sufficient to understand the emotional pain experienced by Suzie during initial stages of treatment? What mechanisms serve to maintain dysfunctional selves irrespective of the emotional pain invol...