![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction and Principles

Abstract

The introduction includes definitions, metaphors, and principles in coal geology as adopted by coalbed gas. Understanding coalbed gas requires knowledge of global coal endowment, geologic occurrence, geographic distribution, and role of evolution of the dynamic Earth's outer shell on coal accumulations. Coal endowment classified as coal resources and reserves is relevant to coalbed gas-in-place estimates. Reporting coal assets is as diverse as there are countries that practice the classification system. Interaction of global coal supply, demand, and consumption results in vibrant debates on coal use in a carbon-constrained world concerned with greenhouse gas emissions. Peak coal production modeled from Hubert peak oil and predictions when peak years will be reached control coal and coalbed gas fueling the future, which is projected to add 5% coal and 80% gas to new electricity capacity by 2035. A remedy is more efficient electricity-generating technologies with CO2 capture and sequestration deployed in and outside power plants.

Keywords

Carbon-constrained world; Carbon dioxide capture and sequestration; Carbon dioxide emission factors; Coal classification system and reporting codes; Coal endowment; Coal peak production; Coal reserves; Coal resources; Coalbed gas-in-place; Geologic and geographic coal distribution and accumulation

Outline

Introduction

Philosophical Overview and Scope

Learning Metaphors

Coal Metaphors

Coalbed Gas Metaphors

Definitions and Terminologies

“Dirty” Coal vs “Clean” Coal

Basic Principles

Coal Occurrence in the Geologic Past

Geologic Coal Distribution

Geographic Coal Distribution

Role of the Dynamic Earth Outer Shell

Global Coal Endowment

Concepts of Coal Resources and Reserves

International Codes of Reporting Coal Assets

As Practiced by United States

Coal Resource Calculation

As Practiced by Other Countries

As Reported by World Information Agencies

From Past to Future Coal Production

Historical Coal Production

Future Peak Coal Production

Coal Use in a Carbon-Constrained World

Global Impact

Impacts of Coal Use in the United States

Summary

Key Items

• Coalbed gas has emerged as an important energy source and understanding this resource requires the knowledge of elements of coal geology.

• The diverse heritage of coal and the maturing field of coalbed gas have given rise to definitions, and terminologies that are used throughout this book.

• Ability to comprehend basic principles is the key to extrapolate from coal science to engineering-applied coalbed gas.

• Understanding the global coal endowment, occurrence, and distribution related to the dynamic structural changes in the Earth's outer shell through geologic time is essential to the exploitation of coalbed gas.

• Vast global coal resources of 9–27 trillion metric tons (mt) potentially hold coalbed gas-in-place of 67–252 trillion m3 (Tcm) based on comparisons with producing American fields.

• About 2100 known coal deposits from Late Devonian (380 million years ago or mya) to Pliocene (3 mya) in age are identified resources/reserves in 74 countries and are inferred resources in 27 other countries.

• Peak coal production following M. King Hubbert peak oil theory has led to forecasts of exhaustion of global coal reserves to 90% in 2070, global peak coal production in 2050, and in the United States as early as 2060 and as late as 2105.

• Despite projection of global peak coal production and reserve exhaustion occurring within this century, coal will continue to fuel our foreseeable future with 2.5–3.5% of the global total coal resource having been consumed.

• Potential reduction of coal consumption and CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants using more efficient technology (e.g. supercritical, ultra-supercritical power plants) and CO2 capture and sequestration is believed to be the key to future of coal. Availability of natural gas and environmental challenges for coal use have limited construction of power plants in the United States with 5% of new capacity of electricity for proposed plants to be fueled by coal. However, developing countries will accelerate the construction of new coal plants to generate electricity and are unconstrained by CO2 emissions.

• Emergence of unconventional gases (e.g. coalbed gas, shale gas) for power generation is a positive alternative in a carbon-constrained world. According to U.S. Energy Information Administration, 80% of the new capacity of electricity for proposed power plants will be fueled by natural gas.

Introduction

This introductory chapter discusses the philosophy and scope of the book but more importantly, it introduces the reader to the terminology, definition, and fundamentals of coal and coalbed gas. The mixing of the long-established principles of coal geology and maturing precepts of coalbed gas, as an emerging unconventional energy, has introduced entirely rich subjects that blend old and new concepts in this book for a target multidisciplinary audience. A result of the mixture of old and new concepts is the proliferation in the literature of metaphors and misconceptions, which are stumbling blocks to familiarizing, learning, and understanding the subject matter, and this is explained in this chapter. The success in blending coal and coalbed gas as a discipline lies in the understanding of the basic principles of coal discussed in the context of its worldwide geologic and geographic distributions as overprinted by the dynamism of the earth's outer shell and constrained by geologic time. Essential to the discussion of basic principles is the foundation of global coal endowment, which is critical to the assessment of coalbed gas because it addresses how coal is measured, calculated, and classified (e.g. resources and reserves) as practiced by different countries and reported by worldwide agencies. The methods of classification and reporting of coal resources and reserves vary from country to country and knowing this difference is critical to the evaluation and application to coalbed gas. Also important is the consideration of how much coal remains in the ground from the standpoint of historical and production perspectives. The past and future coal production is relevant to the deliberation of potential development of coalbed gas resource. Finally, the ramifications of greenhouse gas emission (e.g. carbon dioxide or CO2) from coal use to generate electricity directly impact the continued switch of natural gas (e.g. coalbed gas) for generation of power plants in the future.

Philosophical Overview and Scope

The purpose of this overview is to introduce the reader to the scale and complexity of the subject and scope of the book, with particular emphasis on the trans-disciplinary nature of the state-of-the-art in coal and coalbed gas research and development. More than 30 years ago, coalbed gas emerged globally as a valuable and potential energy resource with a growing role in the exploitation and development of unconventional gas. Unlike other natural gas from conventional reservoirs, coalbed gas is self-sourced with atypical generation, storage, migration, and entrapment of methane within the coal. Another unconventional gas that is self-sourced is shale gas. These reservoir properties and the abundance of coal worldwide at shallow depths make the finding, processing, and development costs of coalbed gas relatively low compared to conventional gas. Increasing global gas supplies for cleaner energy source for electrical generation puts coalbed gas as an important environment-friendly component of the total energy mix (Chapter 2).

The scope of this book is focused toward the study of coalbed gas, which includes: (1) understanding the origin, composition, and physical properties of coal (Chapter 3) and their relationships to coalification, gasification, and gas storage (Chapter 4); (2) the knowledge of coal reservoir characterization in terms of macrolithotype (maceral) composition in relations to coal bed fracture systems, permeability, and porosity as functions of gas flow (Chapter 5); (3) the familiarization of the methodologies of resource assessments of both commodities (Chapter 6); (4) the acquaintance of production advances in relations to drilling and completion technology (Chapter 7); (5) the awareness of implementing environmentally and economically viable disposal of coproduced water to meet regulations (Chapter 8), (6) the knowledge of global development of coalbed gas and potential of coalmine gas recovery and utilization (Chapter 9); and the consideration of the short and long term outlook of coal and coalbed gas, and the future role of sustainability of coalbed gas through microbial generation and the coal-to-biogenic coalbed gas technology (Chapter 10). Thus, the key to the success of improving sustainability of coal and coalbed gas to fuel the foreseeable future and beyond is a better understanding of their economic and environmental impacts in relations to the carbon-constrained world and technological advances.

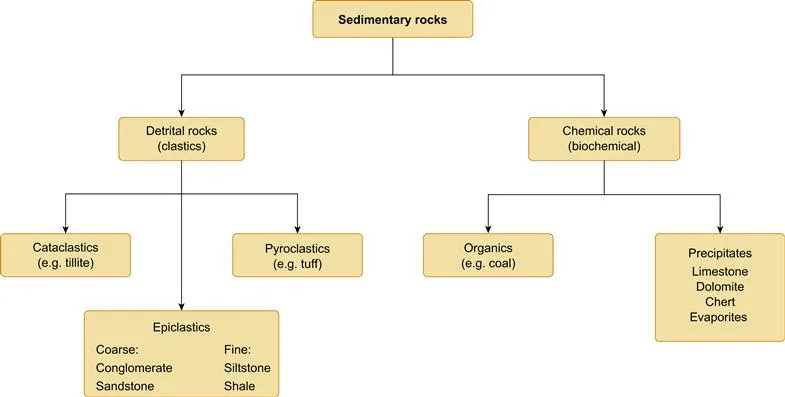

Philosophically, because of the inherent litho-genetic relationship of coal and coalbed gas, one cannot be separated from the other in order to elevate the level of comprehension of both energies to meet new challenges in their exploration and development. Coal is a physically unique reservoir almost totally composed of organic matter, which is different in characteristics compared to other natural gas reservoir rocks composed of epiclastics such as sandstones, siltstones, shales, and precipitates (Figure 1.1). Early exploitation of coalbed gas relied on fairly well-defined resources from surface and subsurface mapping of coal beds. However, the lateral and vertical behaviors of coal beds are sensitive to depositional environments, which vary greatly from coastal to alluvial settings. The coal environments found in various paleoclimatic settings, in turn, dictate the nature of vegetation and type of peat bog/swamp, which control the organic/inorganic matter composition and ultimately potential hydrocarbon byproducts. The process of metamorphism controlled by heat and pressure during burial of the peat precursors, in turn, affects maturation of organic matter and control gasification. Thus, understanding the generation, storage, and entrapment of the gas in the coal plays a major role in predicting economic recoverability and production.

FIGURE 1.1 Flow chart showing the hierarchy of sedimentary rocks divided into detrital and chemical rocks, which in turn, is subdivided into the clastic, organic, and precipitate types.

The technical aspect and success of drilling and completion of coalbed gas wells depend on the characterization of the coal reservoir. Often the ease or difficulty of drilling through the reservoir rock depends on the types of maceral composition, bedding planes, and presence or absence of fractures or cleat...