![]()

Chapter 1. Introduction

The aim of this book is to present the key underlying signal-processing principles used in software-defined radio (SDR) analysis and design. The various chapters span topics ranging from analog and digital modulation to radio frequency (RF) and digital signal processing and data conversion. Although the intent is to cover material relevant to the signal processing used in SDR, the same material could be applied to study more traditional radio architectures.

1.1. The Need for Software-Defined Radio

The SDR forum[1] defines SDR as a “radio in which some or all of the physical layer functions are software defined.” This implies that the architecture is flexible such that the radio may be configured, occasionally in real time, to adapt to various air standards and waveforms, frequency bands, bandwidths, and modes of operation. That is, the SDR is a multifunctional, programmable, and easy to upgrade radio that can support a variety of services and standards while at the same time provide a low-cost power-efficient solution. This is definitely true compared to, say, a Velcro approach where the design calls for the use of multiple radios employing multiple chipsets and platforms to support the various applications. The Velcro approach is almost inevitably more expensive and more power hungry and not in the least compact. For a device that supports multi-mode multi-standard functionality, SDR offers an overall attractive solution to a very complex problem. In a digital battlefield scenario, for example, a military radio is required to provide an airborne platform with voice, data, and video capability over a wide spectrum with full interoperability across the joint battle-space. A traditional legacy Velcro approach in this case would not be feasible for the reasons listed above. In order to create a more adaptable and easily upgradeable solution, the Department of Defense and NATO created the Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) initiative to develop a family of software-defined and cognitive radios that would support interoperability across frequency bands and waveforms as well as satisfy the ease of upgradeability and configurability mandated by modern warfare.

1 See www.sdrforum.org

In the commercial world, the need to adopt SDR principles is becoming more and more apparent due to recent developments in multi-mode multi-standard radios and the various complex applications that govern them. The flexibility of SDR is ideally suited for the various quality-of-service (QoS) requirements mandated by the numerous data, voice, and multimedia applications. Today, many base-station designs employ SDR architecture or at least some technology based on SDR principles. On the other hand, surely but slowly, chipset providers are adopting SDR principles in the design of multi-mode multi-standard radios destined for small form-fit devices such as cellphones and laptops [1].

1.2. The Software-Defined Radio Concept

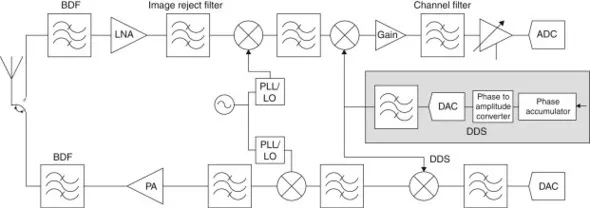

The SDR architecture is a flexible, versatile architecture that utilizes general-purpose hardware that can be programmed or configured in software [2]. Compared to traditional architectures that employ quadrature sampling, SDR radios that employ intermediate frequency (IF) sampling tend to do more signal processing in the digital domain. This particular radio architecture, shown conceptually in Figure 1.1, moves the data conversion closer to the antenna. However, more digital signal processing should by no means imply that the radio is any easier to design or that IF-sampling is superior to quadrature sampling. All it means is that IF-sampling architecture could possibly afford more flexibility in supporting multiple waveforms and services at a reasonable cost and complexity. Furthermore, IF-sampling architecture does not imply that the ensuing design becomes any less complicated or any more robust!

Figure 1.1. Ideal IF-sampling transceiver (digital section not shown) for a TDD system

As a matter of fact, the added flexibility of the radio serves to add to its complexity, especially when dealing with coexistence scenarios and interference mitigation. However, the advantage of SDR over traditional solutions stems from its adaptability to its environment and the number and type of application that it can support. This can be accomplished since the hardware itself and its operation is abstracted completely from the software via a middleware layer known as the hardware abstraction layer (HAL). The purpose of the HAL is to enable the portability and the reusability of software [3]. This common framework enables the development and deployment of various applications without any dependencies on the particular radio hardware.

The SDR concept further assumes certain smarts in the antenna, the RF, and the DSP. In the case of the antenna, this is manifested in terms of its flexibility to tuning to various bands, and its adaptability in terms of beamforming (self-adapting and self-aligning), MIMO operations, and interference rejection (self-healing). Obviously these aims, when it comes to the antenna, are much easier said than done. In terms of analog and digital signal processing, the SDR manages the various stages of the RF to make it more adaptable to its ever-changing environment in order to achieve the desired QoS. Likewise, this flexibility is extended to the data conversion mixed-signal blocks that are configured to receive the desired signal. This entails changing the sampling rate of the converter and its resolution depending on the environment (e.g., blockers, interferers, IF frequency, etc.) and the signaling scheme in a scalable, power-efficient manner that guarantees adequate performance. The digital signal processing is also configured and programmed to complement the RF in terms of filtering, for example, and to perform the various modem functionalities. The modem is designed to support multiple waveforms employing various data rates and modulation schemes (e.g., spread spectrum, OFDM, etc.). In most applications, this is done using a field programmable gate array (FPGA) with application specific capabilities. This endows the radio with real-time reconfiguration and reprogramming capacity, which allows it to roam over various networks in different geographical regions and environments supporting multiple heterogeneous applications. The efficient implementation of such a radio relies on robust common hardware platform architectures and design principles as defined and outlined in the Software Communication Architecture (SCA) standard supported by the SDR forum and adopted by the Joint Program Office (JPO).

1.3. Software Requirements and Reconfigurability

Current SDR implementations mostly rely on reconfigurable hardware to support a particular standard or waveform while the algorithms and the various setups for other waveforms are stored in memory. Although application-specific integrated circuits lead to the most efficient implementation of a single-standard radio, the same cannot be said when addressing a multi-mode multi-standard device. For a device with such versatility, the ASIC could prove to be very complex in terms of implementation and inefficient in terms of cost and power consumption. For this reason, SDR designers have turned to FPGAs to provide a flexible and reconfigurable hardware that can support complex and computationally intensive algorithms used in a multitude of voice, data, and multimedia applications.

In this case, one or more FPGAs are typically used in conjunction with one or more DSPs, and one or more general-purpose processors (GPPs) and/or microcontrollers to simultaneously support multiple applications. FPGAs are typically configured at startup and with certain new architectures can be partially configured in real time. Despite all of their advantages, however, the industry still has not adopted FPGA platforms for use in handheld and portable devices due to their size, cost, and power consumption. Similarly, DSPs and GPPs can also be programmed in real time from memory, allowing for a completely flexible radio solution. Unlike dedicated DSPs used in single standard solutions, SDR employs programmable DSPs that use the same computational kernels for all the baseband and control algorithms.

1.4. Aim and Organization of the Book

The aim of this book is to provide the analog and digital signal processing tools necessary to design and analyze an SDR. The key to understanding and deriving the high-level requirements that drive the radio specifications are the various waveforms the radio intends to support. To do so, a thorough understanding of common modulation waveforms and their key characteristics is necessary. These high level requirements are then disseminated onto the various radio blocks, namely the antenna, the RF, the mixed-signal data conversion (ADC and DAC) blocks, and the digital signal processing block. Of course there are other key components related to the various processors and controllers, and the software and middleware. These topics are beyond the scope of this book.

The book is divided into four sections presented in ten chapters. Section 1 is comprised of Chapters 2 and 3. Chapter 2 deals with analog modulation techniques that are still relevant and widely in use today. Spectral shaping functions and their implementations are also discussed in detail. Chapter 2 addresses digital modulation schemes ranging from simple M-PSK methods to spread spectrum and OFDM. In both chapters figures of merit and performance measures such as SNR and BER under various channel conditions are provided.

Section 2 deals mainly with the RF and analog baseband. This section is divided into three chapters. Chapter 4 addresses the basics of noise and link budget analysis. Chapter 5 deals with nonlinearity specifications and analysis of memoryless systems. Design parameters such as second and third order input-referred intercept points, intermodulation products, harmonics, cross-modulation, and adjacent channel linearity specifications are a few of the topics discussed. Similarly, Chapter 6 further addresses RF and analog design principles and analysis techniques with special emphasis on performance and figures of merit. Topics include receiver selectivity and dynamic range, degradation due to AM/AM and AM/PM, frequency accuracy and tuning, EVM and waveform quality factor and adjacent channel leakage ratio are among the topics discussed.

Section 3 addresses sampling and data conversion. This section is comprised of Chapters 7, 8, and 9. In Chapters 7, the basic principles of baseband and bandpass sampling are studied in detail. The resolution of the data converter as related to sampling rate, effective number of bits, peak to average power ratio, and bandwidth are derived. The chapter concludes with an in-depth analysis of the automatic gain control (AGC) algorithm. In Chapter 8, the various Nyquist sampling converter architectures are examined in detail. Particular attention is paid to the pros and cons of each architecture as well as the essential design principles and performance of each. Chapter 9 discusses the principles of oversampled data converters. The two main architectures, namely continuous-time and discrete-time ΔΣ...