eBook - ePub

From Molecules to Networks

An Introduction to Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience

- 656 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Molecules to Networks

An Introduction to Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience

About this book

An understanding of the nervous system at virtually any level of analysis requires an understanding of its basic building block, the neuron. From Molecules to Networks provides the solid foundation of the morphologic, biochemical, and biophysical properties of nerve cells. All chapters have been thoroughly revised for this second edition to reflect the significant advances of the past 5 years. The new edition expands on the network aspects of cellular neurobiology by adding a new chapter, Information Processing in Neural Networks, and on the relation of cell biological processes to various neurological diseases. The new concluding chapter illustrates how the great strides in understanding the biochemical and biophysical properties of nerve cells have led to fundamental insights into important aspects of neurodegenerative disease.

- Written and edited by leading experts in the field, the second edition completely and comprehensively updates all chapters of this unique textbook

- Discusses emerging new understanding of non-classical molecules that affect neuronal signaling

- Full colour, professional graphics throughout

- Includes two new chapters: Information Processing in Neural Networks - describes the principles of operation of neural networks and the key circuit motifs that are common to many networks in the nervous system. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Neurodegenerative Disease - introduces the progress made in the last 20 years in elucidating the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying brain disorders, including Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson disease, and Alzheimer's disease

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Molecules to Networks by Ruth Heidelberger,M. Neal Waxham,John H. Byrne,James L. Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Cellular Components of Nervous Tissue

Patrick R. Hof, Esther A. Nimchinsky, Grahame Kidd, Luz Claudio and Bruce D. Trapp

Several types of cellular elements are integrated to constitute normally functioning brain tissue. The neuron is the communicating cell, and many neuronal subtypes are connected to one another via complex circuitries, usually involving multiple synaptic connections. Neuronal physiology is supported and maintained by neuroglial cells, which have highly diverse and incompletely understood functions. These include myelination, secretion of trophic factors, maintenance of the extracellular milieu, and scavenging of molecular and cellular debris from it. Neuroglial cells also participate in the formation and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier, a multicomponent structure that is interposed between the circulatory system and the brain substance and that serves as the molecular gateway to brain tissue.

Neurons

The neuron is a highly specialized cell type and is the essential cellular element in the central nervous system (CNS). All neurological processes are dependent on complex cell–cell interactions between single neurons and/or groups of related neurons. Neurons can be categorized according to their size, shape, neurochemical characteristics, location, and connectivity, which are important determinants of that particular functional role of the neuron in the brain. More importantly, neurons form circuits, and these circuits constitute the structural basis for brain function. Macrocircuits involve a population of neurons projecting from one brain region to another region, and microcircuits reflect the local cell–cell interactions within a brain region. The detailed analysis of these macro- and microcircuits is an essential step in understanding the neuronal basis of a given cortical function in the healthy and the diseased brain. Thus, these cellular characteristics allow us to appreciate the special structural and biochemical qualities of a neuron in relation to its neighbors and to place it in the context of a specific neuronal subset, circuit, or function.

Broadly speaking, therefore, there are five general categories of neurons: inhibitory neurons that make local contacts (e.g., GABAergic interneurons in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex), inhibitory neurons that make distant contacts (e.g., medium spiny neurons of the basal ganglia or Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex), excitatory neurons that make local contacts (e.g., spiny stellate cells of the cerebral cortex), excitatory neurons that make distant contacts (eg., pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex), and neuromodulatory neurons that influence neurotransmission, often at large distances. Within these general classes, the structural variation of neurons is systematic, and careful analyses of the anatomic features of neurons have led to various categorizations and to the development of the concept of cell type. The grouping of neurons into descriptive cell types (such as chandelier, double bouquet, or bipolar cells) allows the analysis of populations of neurons and the linking of specified cellular characteristics with certain functional roles.

General Features of Neuronal Morphology

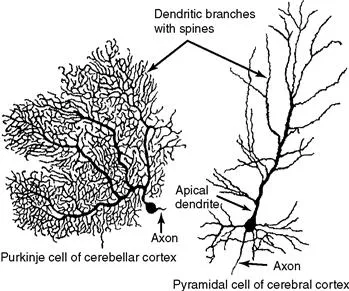

Neurons are highly polarized cells, meaning that they develop distinct subcellular domains that subserve different functions. Morphologically, in a typical neuron, three major regions can be defined: (1) the cell body (soma or perikaryon), which contains the nucleus and the major cytoplasmic organelles; (2) a variable number of dendrites, which emanate from the perikaryon and ramify over a certain volume of gray matter and which differ in size and shape, depending on the neuronal type; and (3) a single axon, which extends, in most cases, much farther from the cell body than the dendritic arbor (Fig. 1.1). Dendrites may be spiny (as in pyramidal cells) or nonspiny (as in most interneurons), whereas the axon is generally smooth and emits a variable number of branches (collaterals). In vertebrates, many axons are surrounded by an insulating myelin sheath, which facilitates rapid impulse conduction. The axon terminal region, where contacts with other cells are made, displays a wide range of morphological specializations, depending on its target area in the central or peripheral nervous system.

Figure 1.1 Typical morphology of projection neurons. (Left) A Purkinje cell of the cerebellar cortex and (right) a pyramidal neuron of the neocortex. These neurons are highly polarized. Each has an extensively branched, spiny apical dendrite, shorter basal dendrites, and a single axon emerging from the basal pole of the cell.

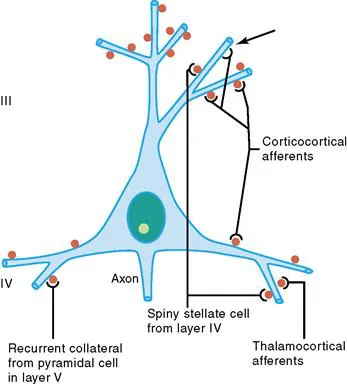

The cell body and dendrites are the two major domains of the cell that receive inputs, and dendrites play a critically important role in providing a massive receptive area on the neuronal surface. In addition, there is a characteristic shape for each dendritic arbor, which can be used to classify neurons into morphological types. Both the structure of the dendritic arbor and the distribution of axonal terminal ramifications confer a high level of subcellular specificity in the localization of particular synaptic contacts on a given neuron. The three-dimensional distribution of dendritic arborization is also important with respect to the type of information transferred to the neuron. A neuron with a dendritic tree restricted to a particular cortical layer may receive a very limited pool of afferents, whereas the widely expanded dendritic arborizations of a large pyramidal neuron will receive highly diversified inputs within the different cortical layers in which segments of the dendritic tree are present (Fig. 1.2) (Mountcastle, 1978). The structure of the dendritic tree is maintained by surface interactions between adhesion molecules and, intracellularly, by an array of cytoskeletal components (microtubules, neurofilaments, and associated proteins), which also take part in the movement of organelles within the dendritic cytoplasm.

Figure 1.2 Schematic representation of four major excitatory inputs to pyramidal neurons. A pyramidal neuron in layer III is shown as an example. Note the preferential distribution of synaptic contacts on spines. Spines are labeled in red. Arrow shows a contact directly on the dendritic shaft.

An important specialization of the dendritic arbor of certain neurons is the presence of large numbers of dendritic spines, which are membranous protrusions. They are abundant in large pyramidal neurons and are much sparser on the dendrites of interneurons (see following text).

The perikaryon contains the nucleus and a variety of cytoplasmic organelles. Stacks of rough endoplasmic reticulum are conspicuous in large neurons and, when interposed with arrays of free polyribosomes, are referred to as Nissl substance. Another feature of the perikaryal cytoplasm is the presence of a rich cytoskeleton composed primarily of neurofilaments and microtubules. These cytoskeletal elements are dispersed in bundles that extend from the soma into the axon and dendrites.

Whereas dendrites and the cell body can be characterized as domains of the neuron that receive afferents, the axon, at the other pole of the neuron, is responsible for transmitting neural information. This information may be primary, in the case of a sensory receptor, or processed information that has already been modified through a series of integrative steps. The morphology of the axon and its course through the nervous system are correlated with the type of information processed by the particular neuron and by its connectivity patterns with other neurons. The axon leaves the cell body from a small swelling called the axon hillock. This structure is particularly apparent in large pyramidal neurons; in other cell types, the axon sometimes emerges from one of the main dendrites. At the axon hillock, microtubules are packed into bundles that enter the axon as parallel fascicles. The axon hillock is the part of the neuron where the action potential is generated. The axon is generally unmyelinated in local circuit neurons (such as inhibitory interneurons), but it is myelinated in neurons that furnish connections between different parts of the nervous system. Axons usually have higher numbers of neurofilaments than dendrites, although this distinction can be difficult to make in small elements that contain fewer neurofilaments. In addition, the axon may be extremely ramified, as in certain local circuit neurons; it may give out a large number of recurrent collaterals, as in neurons connecting different cortical regions, or it may be relatively straight in the case of projections to subcortical centers, as in cortical motor neurons that send their very long axons to the ventral horn of the spinal cord. At the interface of axon terminals with target cells are the synapses, which represent specialized zones of contact consisting of a presynaptic (axonal) element, a narrow synaptic cleft, and a postsynaptic element on a dendrite or perikaryon.

Synapses and Spines

Synapses

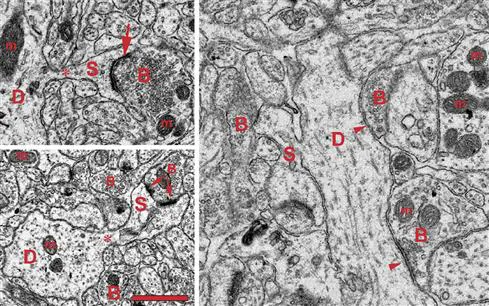

Each synapse is a complex of several components: (1) a presynaptic element, (2) a cleft, and (3) a postsynaptic element. The presynaptic element is a specialized part of the presynaptic neuron’s axon, the postsynaptic element is a specialized part of the postsynaptic somatodendritic membrane, and the space between these two closely apposed elements is the cleft. The portion of the axon that participates in the axon is the bouton, and it is identified by the presence of synaptic vesicles and a presynaptic thickening at the active zone (Fig. 1.3). The postsynaptic element is marked by a postsynaptic thickening opposite the presynaptic thickening. When both sides are equally thick, the synapse is referred to as symmetric. When the postsynaptic thickening is greater, the synapse is asymmetric. Edward George Gray noticed this difference, and divided synapses into two types: Gray’s type 1 synapses are symmetric and have variably shaped, or pleomorphic, vesicles. Gray’s type 2 synapses are asymmetric and have clear, round vesicles. The significance of this distinction is that research has shown that, in general, Gray’s type 1 synapses tend to be inhibitory, while Gray’s type 2 synapses tend to be excitatory. This correlation greatly enhanced the usefulness of electron microscopy in neuroscience.

Figure 1.3 Ultrastructure of dendritic spines (S) and synapses in the human brain. Note the narrow spine necks (asterisks) emanating from the main dendritic shaft (D) and the spine head containing filamentous material, and the cisterns of the spine apparatus particularly visible in the lower panel spine. The arrows on the left panels point to postsynaptic densities of asymmetric excitatory synapses (arrows). The apposed axonal boutons (B) are characterized by round synaptic vesicles. A perforated synapse is shown on the lower left panel. The panel at right shows two symmetric inhibitory synapses (arrowheads) on a large dendritic shaft (D). In this case the axonal boutons (B) contain some ovoid vesicles compared to the ones in asymmetric synapses. The dendrites and axons contain numerous mitochondria (m). Scale bar = 1 μm. Electron micrographs courtesy of Drs. S.A. Kirov and M. Witcher (Medical College of Georgia), and K.M. Harris (University of Texas – Austin).

In cross section on electron micrographs, a synapse looks like two parallel lines separated by a very narrow space (Fig. 1.3). Viewed from the inside of the axon or dendrite, it looks like a patch of variable shape. Some synapses are a simple patch, or macule. Macular synapses can grow fairly large, reaching diameters over 1 μm. The largest synapses have discontinuities or holes within the macule and are called perforated synapses (Fig. 1.3). In cross section, a perforated synapse may resemble a simple macular synapse or several closely spaced smaller macules.

The portion of the presynaptic element that is apposed to the postsynaptic element is the active zone. This is the region where the synaptic vesicles are concentrated and where, at any time, a small number of vesicles are docked and presumably ready for fusion. The active zone is also enriched with voltage gated calcium channels, which are necessary to permit activity-dependent fusion and neurotransmitter release.

The synaptic cleft is truly a space, but its properties are essential. The width of the cleft (~20 μm) is critical because it defines the volume in which each vesicle releases its contents, and therefore, the peak concentration of neurotransmitter upon release. On the flanks of the synapse, the cleft is spanned by adhesion molecules, which are believed to stabilize the cleft.

The postsynaptic element may be a portion of a soma or a dendrite, or rarely, part of an axon. In the cerebral cortex, most Gray’s type 1 synapses are located on somata or dendritic shafts, while most Gray’s type 2 synapses are located on dendritic spines, which are specialized protrusions of the dendrite. A similar segregation is seen in cerebellar cortex. In nonspiny neurons, symmetric and asymmetric synapses are often less well separated. Irrespective of location, a postsynaptic thickening marks the postsynaptic element. In Gray’s type 2 synapses, the postsynaptic thickening (or postsynaptic density, PSD), is greatly enhanced. Among the molecules that are associated with the PSD are neurotransmitter receptors (e.g., NMDA receptors) and molecules with less obvious function, such as PSD-95.

Spines

Spines are protrusions on the dendritic shafts of so...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Contributors

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Chapter 1. Cellular Components of Nervous Tissue

- Chapter 2. Subcellular Organization of the Nervous System: Organelles and Their Functions

- Chapter 3. Energy Metabolism in the Brain

- Chapter 4. Electrotonic Properties of Axons and Dendrites

- Chapter 5. Membrane Potential and Action Potential

- Chapter 6. Molecular Properties of Ion Channels

- Chapter 7. Dynamical Properties of Excitable Membranes

- Chapter 8. Release of Neurotransmitters

- Chapter 9. Pharmacology and Biochemistry of Synaptic Transmission: Classical Transmitters

- Chapter 10. Nonclassic Signaling in the Brain

- Chapter 11. Neurotransmitter Receptors

- Chapter 12. Intracellular Signaling

- Chapter 13. Regulation of Neuronal Gene Expression and Protein Synthesis

- Chapter 14. Modeling and Analysis of Intracellular Signaling Pathways

- Chapter 15. Connexin- and Pannexin-Based Channels in the Nervous System: Gap Junctions and More

- Chapter 16. Postsynaptic Potentials and Synaptic Integration

- Chapter 17. Complex Information Processing in Dendrites

- Chapter 18. Information Processing in Neural Networks

- Chapter 19. Learning and Memory: Basic Mechanisms

- Chapter 20. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Neurodegenerative Disease

- Index