Personalized Immunosuppression in Transplantation

Role of Biomarker Monitoring and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Personalized Immunosuppression in Transplantation

Role of Biomarker Monitoring and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

About this book

Personalized Immunosuppression in Transplantation: Role of Biomarker Monitoring and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring provides coverage of the various approaches to monitoring immunosuppressants in transplant patients, including the most recently developed biomarker monitoring methods, pharmacogenomics approaches, and traditional therapeutic drug monitoring.The book is written for pathologists, toxicologists, and transplant surgeons who are involved in the management of transplant patients, offering them in-depth coverage of the management of immunosuppressant therapy in transplant patients with the goal of maximum benefit from drug therapy and minimal risk of drug toxicity.This book also provides practical guidelines for managing immunosuppressant therapy, including the therapeutic ranges of various immunosuppressants, the pitfalls of methodologies used for determination of these immunosuppressants in whole blood or plasma, appropriate pharmacogenomics testing for organ transplant recipients, and when biomarker monitoring could be helpful.- Focuses on the personalized management of immunosuppression therapy in individual transplant patients- Presents information that applies to many areas, including gmass spectrometry, assay design, assay validation, clinical chemistry, and clinical pathology- Provides practical guidelines for the initial selection and subsequent modifications of immunosuppression therapy in individual transplant patients- Reviews the latest research in biomarker monitoring in personalizing immunosuppressant therapy, including potential new markers not currently used, but with great potential for future use- Explains how monitoring graft-derived, circulating, cell free DNA has shown promise in the early detection of transplant injury in liquid biopsy

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Overview of the pharmacology and toxicology of immunosuppressant agents that require therapeutic drug monitoring

Keywords

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Calcineurin Inhibitors

1.2.1 Cyclosporine A

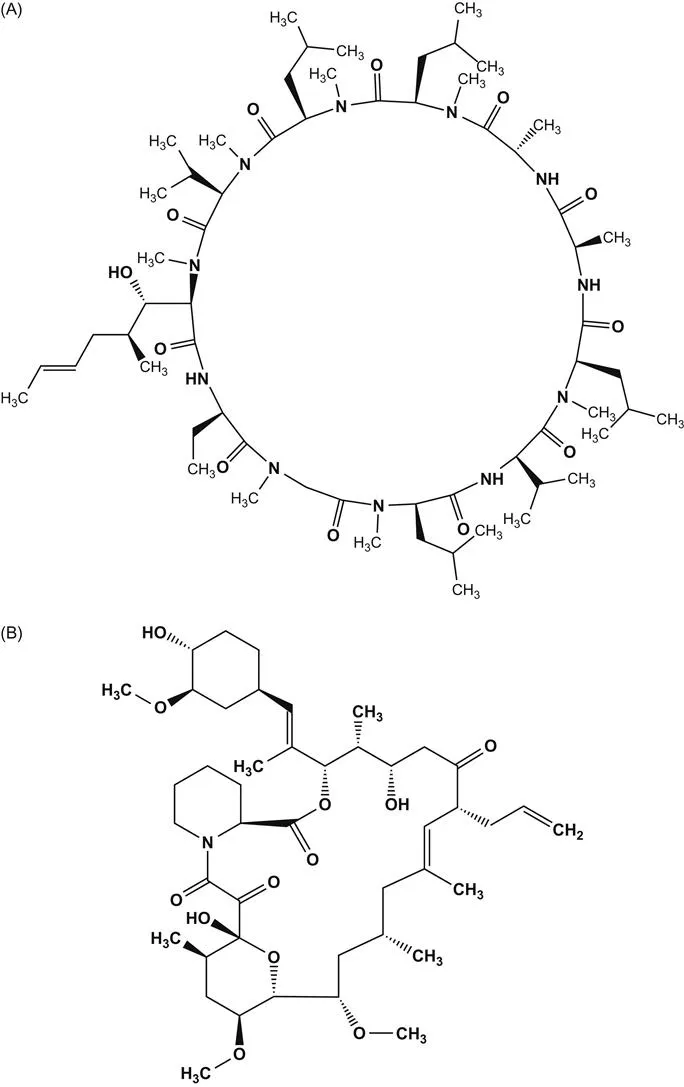

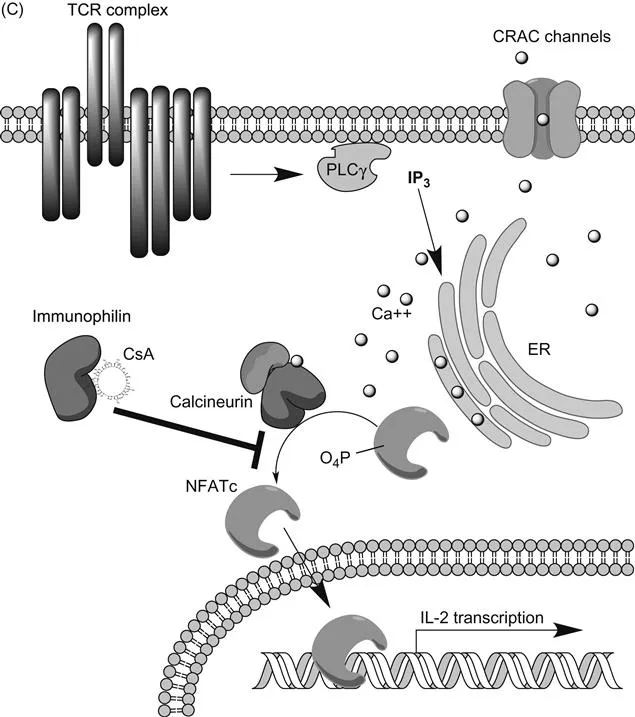

(A) Structure of cyclosporine A; (B) structure of tacrolimus;(C) schematic of calcineurin–NFATc signaling pathway in T cells that is inhibited by CsA and TRL. CRAC channel, calcium release activated channel (Orai1); PLCγ, phospholipase Cγ; IP3, inositol triphosphate.

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1. Overview of the pharmacology and toxicology of immunosuppressant agents that require therapeutic drug monitoring

- Chapter 2. Limitations of immunoassays used for therapeutic drug monitoring of immunosuppressants

- Chapter 3. Application of liquid chromatography combined with mass spectrometry or tandem mass spectrometry for therapeutic drug monitoring of immunosuppressants

- Chapter 4. Monitoring free mycophenolic acid concentration: Is there any clinical advantage?

- Chapter 5. Pharmacogenomics aspect of immunosuppressant therapy

- Chapter 6. Biomarker monitoring in immunosuppressant therapy: An overview

- Chapter 7. Graft-derived cell-free DNA as a marker of graft integrity after transplantation

- Chapter 8. Biomarkers of tolerance in kidney transplantation

- Chapter 9. Intracellular concentrations of immunosuppressants

- Chapter 10. Markers of lymphocyte activation and proliferation

- Chapter 11. Monitoring calcineurin inhibitors response based on NFAT-regulated gene expression

- Index