1.1 Fukushima Accident

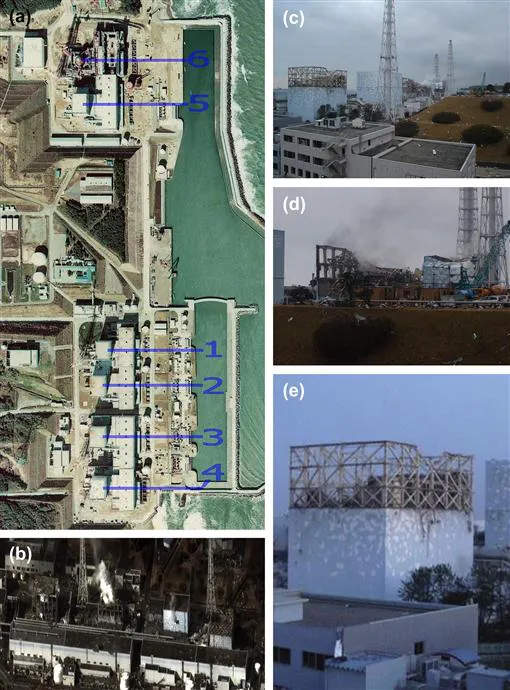

The Fukushima accident happened due to the failure of the cooling system of the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant (NPP) after the Tohoku earthquake and the subsequent unexpectedly high tsunami waves on 11 March 2011 (IAEA, 2011; NSCJ, 2011; NISA, 2012; NERH, 2012; TEPCO, 2012). Due to the damage of the electrical network, as well as the emergency diesel generators, it was not possible to provide electricity to cool nuclear reactors and the fuel storage pools, which resulted in numerous explosions and total damage of the Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 (a–j) Views of the damaged Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant. (Source: (a,b) - Wikipedia; (c–j) - Reprinted with permission from TEPCO).

The atmospheric radionuclide releases during the Fukushima accident were estimated to be the highest for 131I (153–160 PBq) and 137Cs (13–15 PBq) (Chino et al., 2012). Stohl et al. (2012) estimated even higher atmospheric releases for 137Cs (23–50 PBq). The discharged radioactive material, in addition to 131I and 137Cs, also included 134Cs, 132Te, 132I, 136Cs, and other radionuclides, as well as radioactive noble gases (133Xe, 135Xe) (Bowyer et al., 2011). The contribution of 134Cs was similar to that of 137Cs, as the 134Cs/137Cs activity ratio was close to 1 (Masson et al., 2011).

The Fukushima accident was classified by the Government of Japan on the international nuclear and radiological event scale at the maximum level of 7, similar to the Chernobyl accident, which happened in 1986 in the former Soviet Union (presently Ukraine) (IAEA, 2003; WHO, 2005).

Apart from the contamination of the Japanese territory (Hirose, 2012; Kanai, 2012; Tanaka et al., 2012), the Japan Sea (Inoue et al., 2012a), and the Korean Peninsula (Hernández-Ceballos et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012), due to prevailing western winds, the radionuclides emitted to the atmosphere were mainly transported from Fukushima over the Pacific Ocean (Kameník et al., 2013), then to North America (Bowyer et al., 2011; Biegalski et al., 2012; Diaz-Leon et al., 2011; Sinclair et al., 2011), the Atlantic Ocean, Europe (Baeza et al., 2012; Barsanti et al., 2012; Beresford et al., 2012; Bikit et al., 2012; Bossew et al., 2012; Carvalho et al., 2012; Clemenza et al., 2012; Cosma et al., 2012; Evrard et al., 2012; Ioannidou et al., 2012; Kritidis et al., 2012; Kirchner et al., 2012; Loaiza et al., 2012; Lujaniené et al., 2012a,b, 2013; Manolopoulou et al., 2011; Perrot et al., 2012; Pham et al., 2012; Piňero García and Ferro García, 2012; Pittauerova et al., 2011; Povinec et al., 2012a,c, Povinec et al., 2013a,b; Tositti and Brattich, 2012), Arctic (Paatero et al., 2012), and back into Asia. In the beginning of April, the global atmosphere had been labeled with Fukushima-derived radionuclides (Hernández-Ceballos et al., 2012; Masson et al., 2011; Povinec et al., 2013a). The released radionuclides were mostly deposited over the North Pacific Ocean (about 80%), about 20% was deposited over Japan, and less than about 1% was deposited over the Atlantic and Europe (Morino et al., 2011; Stohl et al., 2012; Yoshida and Kanda, 2012).

Except atmospheric radionuclide releases which occurred mostly due to hydrogen explosions at the Fukushima NPP, large amounts of liquid radioactive wastes were directly discharged from the Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP into the ocean. Large volume of contaminated water was produced during emergency cooling of reactors using fresh water, and later also by seawater. Some of this water was unintentionally discharged directly to the sea, which widely contaminated coastal waters off the Fukushima NPP, as reported by the Tokyo Electric Power Company and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and other investigators (Aoyama et al., 2012, 2013; Buesseler et al., 2011, 2012; Honda et al., 2012; MEXT, 2012; Povinec et al., 2012a,c, 2013b; TEPCO, 2012; Tsumune et al., 2012). The total amounts of 137Cs directly released into the sea have been estimated to range from 1 to 4 PBq (Dietze and Kriest, 2012; JG, 2011; Kawamura et al., 2011; Tsumune et al., 2012) to 16.2 ± 1.6 PBq (Rypina et al., 2013), and to 27 ± 15 PBq (Bailly du Bois et al., 2012). As the cooling water directly interacted with ruptured nuclear fuel rods, it has been estimated that 0.1∼1 PBq of 90Sr has also been released to the ocean (Povinec et al., 2012b).

The direct discharge of contaminated water to the sea has significantly elevated radionuclide concentrations in coastal seawater, as well as in the northwestern (NW) Pacific Ocean. The peak 137Cs values were observed at the discharge point of the Fukushima NPP to the sea on 30 March (47 kBq/l) and on 6 April (68 kBq/l) (TEPCO, 2012). Several papers have already discussed 134Cs and 137Cs concentrations in surface waters of the NW Pacific Ocean. In the open ocean, the 137Cs activity concentrations ranged from a few millibecquerels per liter to a few becquerels per liter (Aoyama et al., 2012; Buesseler et al., 2011, 2012; Honda et al., 2012; Inoue et al., 2012b; Povinec et al., 2013b).

1.2 Sources of Radionuclides in the Environment

There are five main sources of radionuclides that could be found in the environment prior to the Fukushima accident:

1. Natural: cosmogenic radionuclides—results of interactions of cosmic rays with atoms in the atmosphere and their subsequent deposition on the Earth and the ocean surface (e.g. 3H, 7Be, 10Be, 14C, 26Al, 53Mn, etc.).

2. Natural: primordial radionuclides (e.g. 40K, 238U, 232Th) and their decay products (e.g. 226Ra, 230Th, etc.) found in the Earth’s crust; due to radon emanation, its decay products are also found in the atmosphere, and then after deposition, in the terrestrial and marine environments (e.g. 210Po, 210Pb, etc.).

3. Anthropogenic: global fallout radionuclides—produced during atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons (e.g. 3H, 14C, 90Sr, 137Cs, Pu isotopes, 241Am, etc.).

4. Anthropogenic: radionuclides released from nuclear installations—mostly from reprocessing nuclear facilities (e.g. 3H, 14C, 90Sr, 99Tc, 129I, 137Cs, etc.).

5. Anthropogenic: radionuclides released during the Chernobyl accident which occurred in 1986 (e.g. 137Cs, Pu isotopes, etc.)

The largest amount of radionuclides (∼950 PBq of 137Cs) released to the atmosphere up to now, representing the main source of anthropogenic radionuclides in the world ocean, has been, however, global fallout resulting from atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons carried out mainly in the 1950s and the early the 1960s (Livingston and Povinec, 2002; UNSCEAR, 1993, 2008). Although global fallout is the dominant source of anthropogenic radionuclides in the environment, large quantities of radioactive materials released to the atmosphere and coastal waters following a nuclear accident at the Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP increased considerably the 137Cs concentrations in coastal seawater off Fukushima up to eight orders of magnitude above the global fallout background (TEPCO, 2012; MEXT, 2012).

We shall focus in this book only on a few anthropogenic radionuclides, specifically on those, that have been frequently studied...