eBook - ePub

Principles of Tissue Engineering

- 1,678 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Principles of Tissue Engineering

About this book

Now in its fifth edition, Principles of Tissue Engineering has been the definite resource in the field of tissue engineering for more than a decade. The fifth edition provides an update on this rapidly progressing field, combining the prerequisites for a general understanding of tissue growth and development, the tools and theoretical information needed to design tissues and organs, as well as a presentation by the world's experts of what is currently known about each specific organ system.

As in previous editions, this book creates a comprehensive work that strikes a balance among the diversity of subjects that are related to tissue engineering, including biology, chemistry, material science, and engineering, among others, while also emphasizing those research areas that are likely to be of clinical value in the future.

This edition includes greatly expanded focus on stem cells, including induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, stem cell niches, and blood components from stem cells. This research has already produced applications in disease modeling, toxicity testing, drug development, and clinical therapies. This up-to-date coverage of stem cell biology and the application of tissue-engineering techniques for food production – is complemented by a series of new and updated chapters on recent clinical experience in applying tissue engineering, as well as a new section on the emerging technologies in the field.

- Organized into twenty-three parts, covering the basics of tissue growth and development, approaches to tissue and organ design, and a summary of current knowledge by organ system

- Introduces a new section and chapters on emerging technologies in the field

- Full-color presentation throughout

Information

Chapter 1

Tissue engineering: current status and future perspectives

Prafulla K. Chandra, Shay Soker and Anthony Atala, Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, United States

Abstract

The field of tissue engineering (TE) has made tremendous progress in the past decade and is still evolving. It is not only now possible to control cells and their environments more precisely but also to engineer living tissues and organs of increasing complexities for potential clinical use. New trends and technologies that are positively impacting this field include smart biomaterials, new stem-cell sources, advanced three-dimensional bioprinting, vascular engineering, advanced bioreactors, organoids, microfluidics-based physiological platforms. Current challenges facing this field include availability of dependable cell sources, ideal bioinks, reducing the immunogenicity of TE scaffold, engineering vasculature and innervation in bioengineered tissues, commercialization, and regulatory hurdles. The coming decade is expected to see even more breakthroughs and products that would be successful clinically. The streamlining of regulatory process, coverage of TE therapies by medical insurance, and their greater acceptance by the patient population would accelerate the prospect of TE to become a mainstream medical specialty.

Keywords

Tissue engineering; regenerative medicine; biomaterials; biofabrication; scaffolds; stem cells; cell therapy; 3D bioprinting; bioreactor; nanotechnology; personalized medicine; clinical

Clinical need

Tissue and organ failure due to disease, injury, and developmental defects has become a major economical and healthcare concerns [1]. At present, use of donated tissues and organs is the clinical practice to address this situation. However, due to the shortage of organ donors, the increasing number of people on the transplant waiting lists, and an ever-increasing aging population, dependence on donated tissues and organs is not a practical approach. In addition, due to severe logistical constraints, many organs from donors cannot be matched, transported, and successfully transplanted into a patient within the very limited time available. In the United States alone, more than 113,000 people are on the National Transplant Waiting list and around 17,000 people have been waiting for more than 5 years for an organ transplant (US Department of Health and Human Services, Organ Procurement and Transplantation network; https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov; data as of February, 2019). To address this critical medical need, tissue engineering (TE) has become a promising option. TE and regenerative medicine (RM) are multidisciplinary fields that combine knowledge and technologies from different fields such as biology, chemistry, engineering, medicine, pharmaceutical, and material science to develop therapies and products for repair or replacement of damaged tissues and organs [2,3].

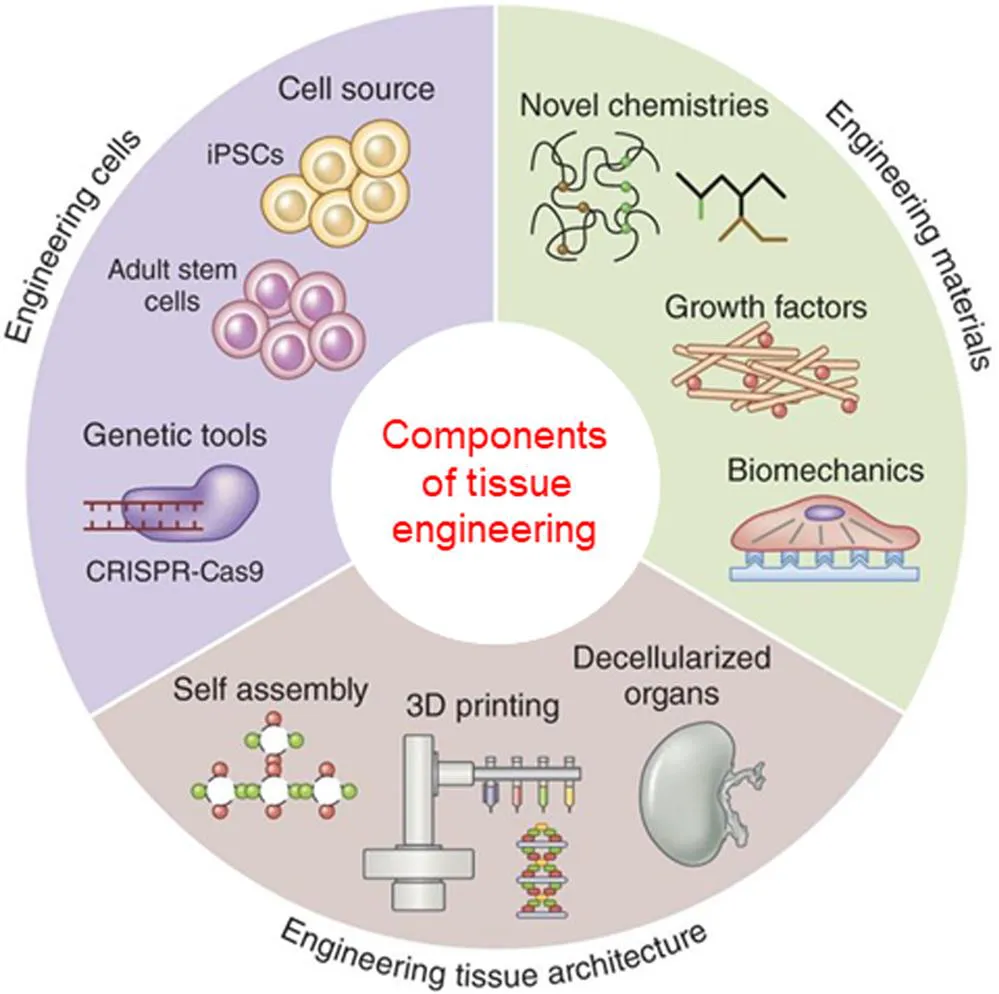

The process of TE is multistep and involves engineering of different components that will be combined to generate the desired neo-tissue or organ (Fig. 1.1). Today, this field has advanced so much that it is being used to develop therapies for patients that have severe chronic disease affecting major organs such as the kidney, heart, and liver. For example, in the United States alone, around 5.7 million people are suffering from congestive heart failure [5], and around 17.9 million people die or cardiovascular diseases globally (World Health Organization data on Cardiovascular disease; https://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/). TE can help such patients by providing healthy engineered tissues (and possibly whole organ in future) to replace their diseased tissue for restoring function. For example, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide health crisis that can be treated, but it also depends on organ donation. In the United States alone, around 30 million people are suffering from CKD (Center for Disease Control & Prevention; National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/pdf/kidney factsheet), while close to 10% of the population is affected worldwide. Liver disease is another healthcare problem, which is responsible for approximately 2 million deaths per year worldwide [6]. Other diseases or conditions that can benefit from TE technologies include skin burns, bone defects, nervous system repair, craniofacial reconstruction, cornea replacement, volumetric muscle loss, cartilage repair, vascular disease, pulmonary disease, gastrointestinal tissue repair, genitourinary tissue repair, and cosmetic procedures. The field of TE, with its goal and promise of providing bioengineered, functional tissues, and organs for repair or replacement could transform clinical medicine in the coming years.

Current state of the field

TE has seen continuous evolution since the past two decades. It has also seen assimilating of knowledge and technical advancements from related fields such as material science, rapid prototyping, nanotechnology, cell biology, and developmental biology. Specific advancements that have benefited TE as a field in recent years include novel biomaterials [7], three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting technologies [8], integration of nanotechnology [9], stem-cell technologies such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [9,10], and gene editing technology such as Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) [11]. All these have led to promising developments in the field that include smart biomaterials, organoids, and 3D tissue for disease modeling and drug development, whole organ engineering, precise control and manipulation of cells and their environments, and personalized TE therapies.

Biomaterials are critical components of many current TE strategies. Recent developments in this field that are benefiting TE include synthesis of new biomaterials that can respond to their local environment and cues (smart biomaterials). Advancements in 3D bioprinting technologies are at the core of many developments in TE. It is now possible to print multiple biocompatible materials (both natural and synthetic), cells, and growth factors together into complex 3D tissues, many with functional vascular networks, which match their counterparts in vivo. We have also learned a great deal about cell sourcing, culture, expansion, and control of differentiation. This is also true for stem cells, where new sources such as placenta, amniotic fluid, and iPSCs have been explored and optimized for use. Vascularization and innervation in bioengineered tissue is a continuing challenge essential to warrant sustained efforts success of tissues implanted in vivo would be very low. Therefore there is a need for greater understanding of vascularization and innervation as applied to bioengineered tissues. This is an ongoing effort, and the results we are seeing from various studies are encouraging. Biofabrication technologies are playing a great role in this regards.

Several engineered tissues are moving toward clinical translation or are already being used in patients. These include cartilage, bone, skin, bladder, vascular grafts, cardiac tissues, etc. [12]. Although, complex tissues such as liver, lung, kidney, and heart have been recreated in the lab and are being tested in animals, their clinical translation still has many challenges to overcome. For in vitro use, miniature versions of tissues called organoids are being created and used for research in disease modeling, drug screening, and drug development. They are also being applied in a diagnostic format called organ-on-a-chip or body-on-a-chip, which can also be used for the above stated applications. Indeed, the development of 3D tissue models that closely resemble in vivo tissue structure and physiology are revolutionizing our understanding of diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer and can also accelerate development of new and improved therapies for multiple diseases and disorders. This approach is also expected to drastically reduce the number of animals that are currently being used for testing and research. In addition, 3D tissue models and organ-on-a-chip or body-on-a-chip platforms can support advancement of personalized medicine by offering patient-specific information on the effects of drugs, therapies, environmental factors, etc.

Development of advanced bioreactors represent another recent developments that are supporting clinical translation of TE technologies. Such bioreactors can better mimic in vivo environments by provide physical and biochemical control of regulatory signals to cells and tissue being cultured. Examples of such control include application of mechanical forces, control of electrical pacing, dynamic culture components, induction of cell differentiation. Incorporation of advanced sensors and imaging capabilities within these bioreactors are also allowing for real-time monitoring of culture parameters such as pH, oxygen consumption, cell proliferation, and factor secretion from a growing tissue. 3D modeling is also a new tool relevant to TE that provides great opportunities and better productivity for translational research, with wide clinical applicability [13]. Recent advancements in specific field that are helping advance TE are discussed next.

Smart biomaterials

Smart biomaterials are biomaterials that can be designed to modulate their physical, chemical, and mechanical properties in response to changes in external stimuli or local physiological environment (Fig. 1.2) [14,15]. Advances in polymer synthesis, protein engineering, molecular self-assembly, and microfabrication technologies have made producing these next-generation biomaterials possible. These biomaterials can respond to a variety of physical, chemical, and biological cues such as temperature, sound, light, humidity, redox potential, pH, and enzyme activity [16,17]. Other unique characteristics displayed by some smart biomaterials are self-healing or shape-memory behavior [18]. The development of biomaterials with highly tunable properties has been driven by the desire to replicate the structure and function of extracellular matrix (ECM). Such materials can enable control of chemical and mechanical properties of the engineered tissue, including stiffness, porosity, cell attachment sites, and water uptake. For hydrogels, use of reversible cross-linking through physical methods, self-assembly, or the...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Tissue engineering: current status and future perspectives

- Chapter 2. From mathematical modeling and machine learning to clinical reality

- Chapter 3. Moving into the clinic

- Part One: The basis of growth and differentiation

- Part Two: In vitro control of tissue development

- Part Three: In Vivo Synthesis of Tissues and Organs

- Part Four: Biomaterials in tissue engineering

- Part Five: Transplantation of engineered cells and tissues

- Part Six: Stem cells

- Part Seven: Gene therapy

- Part Eight: Breast

- Part Nine: Cardiovascular system

- Part Ten: Endocrinology and metabolism

- Part Eleven: Gastrointestinal system

- Part Twelve: Hematopoietic system

- Part Thirteen: Kidney and genitourinary system

- Part Fourteen: Musculoskeletal system

- Part Fifteen: Nervous system

- Part Sixteen: Ophthalmic

- Part Seventeen: Oral/Dental applications

- Part Eighteen: Respiratory system

- Part Nineteen: Skin

- Part Twenty: Tissue-engineered food

- Part Twenty one: Emerging technologies

- Part Twenty two: Clinical experience

- Part Twenty three: Regulation, commercialization and ethics

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Principles of Tissue Engineering by Robert Lanza,Robert Langer,Joseph P. Vacanti,Anthony Atala in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biotechnology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.