- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

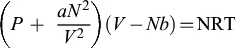

Metallurgy of Fracture: The Mechanics of Metal Failurelooks at the origin of metal defects, their related mechanisms of failure, and the modification of casting procedures to eliminate these defects, clearly connecting the strength and durability of metals with their fabrication process. The book starts with a focus on the fracture of liquids, looking at topics such as homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation, entrainment processes in bifilms and bubbles, furling and unfurling, ingot casting, continuous casting, and more. From there it discusses fracture of liquid and solid state, focusing on topics such as externally and internally initiated tearing. The book then concludes with a section discussing fracture of solid metals covering concepts such as ductility and brittleness, dislocation mechanisms, the relationship between the microstructure and properties of metals, corrosion, hydrogen embrittlement, and more. Improved approaches to fabrication and casting processes that will help eliminate these defects are provided throughout.- Looks at how the fracture of metals originates in the liquid-state due to poor casting practices- Offers improved casting techniques to reduce liquid-state borne fracture- Draws attention to the parallels between fracture initiation in the liquid and solid states- Covers spall tests and how to improve material quality by hot isostatic pressing

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

The fracture of liquids

Abstract

Keywords

1.1. Theoretical strength of liquids

1.1.1. Classical continuum theory

1.1.2. Classical bubble nucleation

1.1.3. Homogeneous nucleation

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The fracture of liquids

- Chapter 2. Fracture in the liquid/solid state

- Chapter 3. Fracture of solids

- Appendices

- Postscript

- References

- Index